|

WHY PIRACY IS GOOD

A tangled (and lengthy) tale of morality.

It's weird how the simplest games can have

the longest stories. Today we're going to talk (well, I'm going to,

anyway) about a couple of games (well, four games, but we'll get to that)

that are about as Zen-basic as it's possible for electronic entertainment

to be. A pair of games which could be played by the one-armed dishwasher

from Robin's Nest (one for the mums and dads, there), a duo that require

all the brainpower of a starving dog pondering the best course of action

to take with a pound of sausages that's just fallen out of an old lady's

shopping bag right under his nose.

And yet, by the time we're done, we'll have

covered inspiration, plagiarism, moral flexibility, flagrant copyright

infringement, public-spiritedness, cultural history, corporate pragmatism,

collective short-sightedness and the proudest moment in your

correspondent's career to date. Which is a lot of stuff, so let's get on

or we'll be here all day.

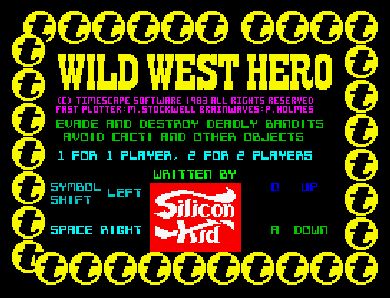

Wild West Hero is one of the most esoteric

games in the history of the Spectrum. It takes Robotron - not the world's

most complex videogame to start with - and distils it down to its most

basic essence. All the enemies except the first level's GRUNTs are

discarded. The cloned human family to be rescued? Gone. The twin-joystick

moving/firing mechanism? No more. There's no fire button in WWH at all, in

fact - your little guy just automatically pumps out a constant stream of

fire in whichever direction he's facing.

No level in Wild West Hero lasts more than

about 10 seconds. Your enemies materialise onscreen and immediately start

shuffling slowly but inexorably towards you. Within moments, they'll

either have got you or you'll have killed them all. No other outcomes are

possible (unless you count killing yourself by colliding with one of the

static obstacles as you bolt for one of the screen's edges, there to

implement the game's core tactic of turning round and massacring the

bandits as they march towards you in single file).

Bandits? Oh yeah. While your avatar is the

same teeny robot dude who appears in Robotron, and the game shares the

coin-op's bright, flashing neon colours and futuristic sound effects, for

some reason your enemies are all big-hatted spaghetti-western cowboys,

with beady yellow eyes peeking out from under their ten-gallon hats. This

inexplicable thematic clash is one of the things that gives WWH its unique

and strange character, but that isn't one of the things on our list, so

we'll move on.

The point is, Wild West Hero owes a clear

and undeniable debt to Robotron, but it's also its own game. Which makes

it pretty weird when you see it gradually metamorphose back into its own

parent.

In the early 1980s, Atarisoft (the home

computer software division of the then-still-massive hardware company) had

invested a lot of effort and money in cracking down on unlicenced

home-version clones of their arcade smash hits.

Eventually, though, some bright spark realised that spending loads of cash

suppressing highly-skilled copies of your intellectual property was

pointlessly counter-productive, when you could turn it to your advantage

instead. Here, after all, were ready-made conversions, ripe for selling

and free from development costs. All Atari had to do was say to the

author, "Turn it over to us and we won't sue you", stick an official badge

on it and sit back and wait for the profits to start rolling in.

Among the first beneficiaries/victims of this

strategy was DJL Software's Z-Man, a direct Pac-Man clone that was by far

the most authentic of the dozens of Spectrum versions cluttering game-shop

shelves. It's one of the great legends of the Speccy gaming era that the

author, David J. Looker, was then approached by Atarisoft with the offer he

couldn't refuse - "Edit this into the official Spectrum version of

Pac-Man and give us it for nothing, or our lawyers will crush you like a tiny

worthless bug" - and a few tweaks later the company proudly made its

debut in the Speccy market with a hastily-relabelled, essentially

blackmailed version of what had

previously been a pirate ripoff of its most valuable licensed franchise.

(Though as an exciting postscript to the

story, the "illegal" Z-Man incarnation of Pac-Man was subsequently given

away on the

covertape of

Speccy magazine Your Sinclair almost 10

years later. An extensive and painstaking investigation into this baffling

turn of events - that is to say, emailing the renowned scientist,

adventurer and gadabout, and more relevantly former YS editor,

J Nash - provided the

following splendid explanation:

"This was because I liked Z-Man, and knew

about Atari and the Nigel Moustache accident, and thought it would be an

appropriate victory for justice and a funny in-joke to buy the world's

most accurate Speccy Pac-Man for the [covertape] under its original name.

Dave, slightly bemused anyone remembered the game, agreed. Inexplicably,

Atarisoft failed to notice. I expect they were still busy spending all the

profits from the conversion of Bump and Jump."

For more information on "the Nigel Moustache

accident", see a forthcoming feature, possibly on an entirely different

website. But meanwhile, back to our story.)

After Z-Man, DJ Looker (Shout out to the massive! -

Ed) moved into "respectable"

development. He coded the excellent Spectrum version of fun Atari coin-op

Road Blasters (which is, coincidentally, the game without which your

correspondent wouldn't be in the videogames industry at all, but that's

another story), then went on to fame and fortune as Your Sinclair's covertape editor, and also, ironically enough, co-invented the highly

controversial "Speedlock" fastloader/anti-copying protocol. But this poacher-turned-gamekeeper tale

isn't why piracy is good (which, particularly alert viewers who are

concentrating unusually hard will recall,

is what this feature is supposedly about). To get to the bottom of that

particular assertion, we first need to take a small tangent.

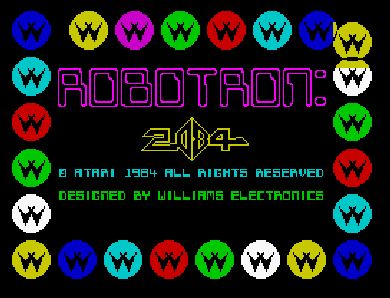

The success of Pac-Man assured Atarisoft of

the wisdom of their cunning co-opt-the-copyists policy, and the strategy

was soon applied to the forbidding task of bringing Williams' awesome

twin-joystick coin-op Robotron 2084 to the

Sinclair machine. Most of the previous

attempts at reproducing the arcade's fast-moving, action-packed mayhem

on the Speccy's primitive 8-bit hardware had produced woeful results, so

Wild West Hero author Paul Holmes was always going to be the man getting a

midnight knock on the door from burly Atarisoft associates armed with

contracts and baseball bats.

(Holmes hadn't been idle since coming up

with WWH - in the meantime he'd also produced the heroically weird

Dustman, a slicker and even more surreal variant on the theme than

Wild West Hero, and one in which the player has to survive assaults from

all manner of cultural detritus. Levels include several cameo appearances

from Pac-Man, a stage called "A Copyright With Teeth" - in which the dustman

is attacked by chomping copyright symbols - and one titled "Out Come The

Heavies", where swinging doors disgorge hordes of huge green robots

uncannily similar to Robotron's indestructible Hulks. These facts may or

may not be coincidental. Dustman, in fact, deserves a feature all of its

own, but WoS can see readers beginning to visibly age already, so we'll

save that for another day.)

The result, as perceptive viewers will have

figured out some time ago, is that Wild West Hero's code became the basis

of the official Speccy Robotron. But that's neither the end nor the point

of our story. Because despite being completed (well, it was glowingly

reviewed by a games magazine, though of course

these days we realise that that doesn't

necessarily mean it was finished - it's surely just a coincidence,

however, that the reviewer from the mag above went on a few months later

to co-found Future Publishing),

Robotron was never

released.

Atarisoft never even got round to

advertising it for the Speccy (something which they did do for a

whole bunch of other games whose conversions were never even started, far

less finished), and the code languished ignored for years, even as the

Speccy carried on for nine more years as a viable gaming platform. (The

company, in fact, abandoned the Spectrum shortly after the completion of

Robotron in 1984, also taking with it a fairly splendid unreleased port of

another fine Williams coin-op, Moon Patrol.) Oddly, no other magazines had

so much as previewed the game, so copies of the finished code were thin on

the ground - so much so that soon, even Holmes himself didn't have one. It

would be almost a decade before anyone ever

thought of Spectrum Robotron again.

The mid-1990s, of course, brought the birth

of emulation. For the first time ever, computers were so powerful that

they could accurately reproduce the behaviour of their ancestors, and the

still-beloved Speccy was one of the very first subjects of the phenomenon.

Soon, archive websites like

World Of Spectrum began to spring up to preserve the cultural

heritage of the medium. But for some games, it was already too late.

Atarisoft no longer existed, neither did Personal Computer Games, and Paul

Holmes didn't have a copy of his own conversion.

The only known surviving Spectrum Robotron

code was an early work-in-progress alpha of Holmes', missing most of the

enemy robot types (for example, there were no Brains on Wave 5, and the

Spectrum's Wave 7 - where the first Tanks appear in the arcade game -

simply completes itself as soon as it starts), and clearly showing the

port's Wild West Hero roots. The player and the enemy robots appear

onscreen in the same way they do in WWH, and destroyed robots melt away

rather than exploding in a shower of particles. At this point, in fact,

apart from the title screen the game more closely resembles Wild West Hero

1.5 than it does Robotron. Which is (if you were wondering) where piracy,

your reporter and his proudest moment come in.

Your correspondent, viewers, has to make a

confession at this point. In the early 1980s, this writer - like pretty

much everyone else, it ought to be said - was a serious and diligent

software pirate. The school playgrounds of the 80s were alive with kids

swapping C90 cassette tapes packed full of the latest games, 20 and 30 at

a time. (Curiously, this hugely widespread buy-one-and-copy-100 practice

somehow entirely failed to destroy the entire

games industry, and the Speccy had a longer commercial life than any

gaming platform before or since.)

The more dedicated copyright infringers,

though, also participated in nationwide piracy networks, trading tapes

with complete strangers from across the country. Your correspondent,

naturally (because if a job's worth doing it's worth doing properly), had

a number of such underground acquaintances, one of whom was "James" from

Glasgow. (Whose name has been changed to reflect the fact that I can't

remember it. For all I know it actually was James.)

"James" had a contact in Atarisoft,

and towards the end of 1984 had casually included copies of Robotron and

Moon Patrol on one of the regular C90s despatched to your

living-on-the-edge reporter. They both swiftly graduated onto your host's

special "My Favourite Games" shelf, but it wasn't until nearly 12 years

later that their true rarity and worth would be fully appreciated.

Y'see, chums, this writer

frequently

speaks

up for the importance of emulation - and even outright piracy - as a

preserver of culture, and he's not just bumping his gums. No other leisure

medium has ever regarded its heritage so carelessly as videogaming (not

even the early BBC, which would commonly record over the only copy of

priceless programmes to save on tape costs), and there are countless games

which have been lost to posterity forever. Without piracy, the Spectrum

ports of Robotron and Moon Patrol would be among them.

Because it was only piracy that enabled your

reporter to contact Paul Holmes several years ago and return his own work

to him (at which point he generously allowed it to be made freely available to

everyone), and even if this writer never achieves anything more worthy

than that in the rest of what passes loosely for a career, he'll leave the

games business a happy man. (Actually, the act of leaving the videogames

business would make anyone a happy man, but that's not strictly

relevant here.) Had it been left in the sole care of the games industry,

Spectrum Robotron simply wouldn't exist any more, and our cultural history

deserves better treatment, and more respect, than that.

The bodies which present themselves as the

guardians of gaming culture aren't just incompetent at the task, they are

in fact

the active enemies of it. Where ELSPA and their ilk should be doing

something worthwhile to preserve gaming's heritage while there's still

time, they devote themselves instead to pointlessly persecuting the very

websites that are actually doing their job for them. (And to chasing

idiotically after small-fry market traders, like an elephant trying to

stamp on a colony of ants.)

The industry attempts, as a matter of

policy, to portray

emulation - not even

piracy - as a mortal danger to its very existence, and is assisted in

doing so by a media that unquestioningly presents the industry's side of

the argument as gospel truth, and an increasingly brainwashed public ready

to believe the industry's farcical

propaganda about

how Al-Qaeda and the IRA and Ian Huntley and the Mafia all started out by

copying Playstation games.

But let's be crystal-clear about this,

viewers, for the avoidance of doubt and confusion. Take it from someone

who's personally been on every single side of the equation at some point

in the last 20 years. Here's the truth:

Emulation does

NOT hurt the videogames industry.

Piracy

does

NOT hurt the videogames industry.

Because if either of them did, then it's

amazingly obvious that - after more than 10 years of the former and 25

years of the latter - the videogames industry would have been long dead by

now, rather being bigger and wealthier now

than it's ever been at any time. The reality is that piracy and emulation

are in truth phenomena whose primary influence on gaming is to save its

legacy from the greedy, narrow-minded, short-sighted recklessness of those

who control the worldwide videogames industry.

Chums, the fact of the matter is that the

cultural heritage of videogaming is safe only in your hands. Recent changes in

the law with regard to copyright

have made the position of old games even more perilous than it used to be.

Now, practically any measures which gamers could take to preserve the

future history of gaming are, either effectively or literally, illegal,

and accordingly are becoming harder and harder to actually enact.

Something needs to be done. And shortly, something will be. Watch this

space.

In the meantime, it's in that same spirit of

preservation that WoS is proud to

offer the downloads below as an illustrative, iNTeRacTIVe accompaniment to

this feature. (Get the emu from its homepage, right-click on the game

files to save them to your hard drive.)

Enjoy them while you still can.

DOWNLOADS

EmuZWin, the best

freeware Speccy emulator (link)

Wild West Hero

Wild West Hero (great PC remake - WoS remix)

Dustman

Robotron 2084 - author's alpha version

Robotron 2084 - beta version, preserved by

piracy

Robotron

2084 - final version, preserved by piracy

Comments? WoS Forum

|

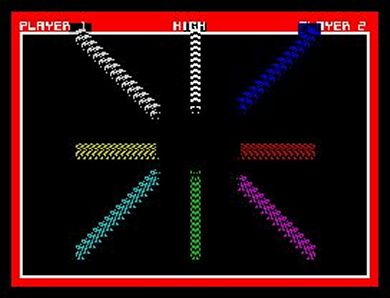

In a fine example of its stripped-down Spartan ethic,

Wild West Hero's title screen also served as its loading screen and

instruction manual.

The key - some might say only - gameplay tactic in WWH was to get to

the edge of the screen then turn back on your pursuers, guns

blazing.

The title screen for the official version didn't take

a lot of extra work. Change a "t" (for "Timescape") to a "W" and

you're practically there.

Wild West Hero's tactics worked in Robotron too, up

to a point (ie the point at which those bastard Enforers up in the corner

killed you).

It's always nice to see people who've brazenly

pinched someone else's intellectual property

asserting their copyright over it...

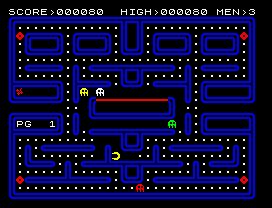

In the old days, cloners used to think that slightly

changing the layout of the Pac-Man maze would protect them from charges of

plagiarism.

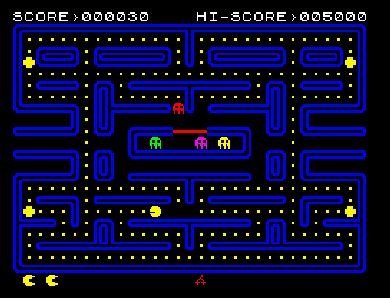

One swift new title screen and suddenly you're all

nice and legit.

With the official seal of approval in place, the

Pac-maze could be safely restored to its proper shape and the power pills

made the right colour.

A typical stage from Dustman. You have to survive

until another dustman comes to rescue you. Or maybe you're rescuing him, I

forget.

Another level ("Out Come The Heavies", to be

specific) of Dustman. Hmm, haven't we met

somewhere before, hulking big green dudes?

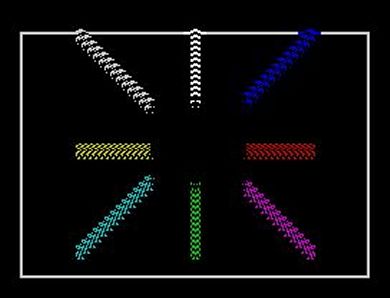

Tracing the development of Speccy Robotron part 1: here we

see the player's "rez-in" materialisation sequence from Wild West Hero.

While this is the same sequence from the alpha

version of Speccy Robotron. Note that the player appears before the enemy

robots.

And this is the rez-in sequence from the finished

version of the game.

For comparison, here's the real arcade version.

Wave 5 of the alpha version of Speccy Robotron. The

GRUNTs and humanoids are present, but the evil Brain Robotrons are

missing.

And here's Wave 5 from the final version, with Brains

present in a

(very) full cast list. Without piracy, you would never have seen this.

Sadly, the Tank Robotrons which should be making

their debut appearance in this wave didn't make it into even the final

version, and are the only enemies missing from

the Speccy version. If only Atarisoft had had the decency to hang on just

a little bit longer, eh?

|