|

WALKING WITH BURKE AND HARE

A brief history of

plagiarism

One of the great ironies about the

videogames industry's powerful and often-voiced objections to copyright

infringement is that, of course, the entire industry was built on a

foundation of that very thing. Almost everyone in charge of a games

publisher today started off engaged in the production of unlicensed clones

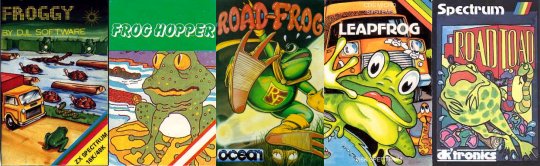

of old arcade games like Pac-Man, Centipede, Donkey Kong, Frogger etc.

Fig.1 - Unashamed ripoffs.

(Often, so shameless was the copying that the publishers wouldn't even

bother to change the name. Later they decided that to foil trademark laws

they'd cunningly change just one or two letters - hence Phoenix would

become "Pheenix", Galaxian would become "Galaxians" or "Galakzian",

and so on.)

As time went on and the industry matured, it

started to clean up its act slightly. Ocean's 1984 conversion of Hunchback

is widely thought to be the first instance of a legitimately-licensed home

computer version of a popular arcade hit, and from then on blatant

unlicenced ripoffs started to become the exception rather than the rule.

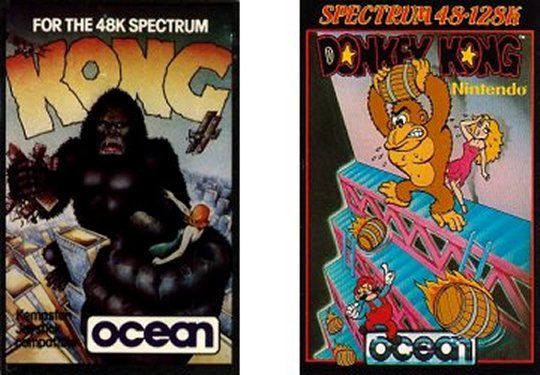

(Interestingly, Ocean, who had published an

unlicenced Donkey Kong clone in 1983, later went on to release an all-new,

officially-badged conversion three years later, licencing the game from an

uncharacteristically forgiving Nintendo. As far as we can tell, this is

the only instance in gaming history of a company publishing both

unlicenced clones and official conversions of the same game.)

Fig.2 - Slightly ashamed ripoffs.

All this meant, however, was that developers

and publishers started to find sneakier ways of ripping off the work of

others. Most boldly of all, a coder called Harry S Price specialised in

slightly rewriting existing titles and selling them as his own work,

sometimes even under the nose-thumbing "Pirate Software" label. (A

detailed breakdown of Price's works and where they were swiped from can be found on

this

page, originally hosted at the currently-offline cl4.org.)

Well-known figures in even today's games

industry got their start in a similar way. For example, the first known

published work of Martyn Brown, currently director of Worms publishers Team 17

(Worms itself, of course, being an unlicenced, uncredited updating of a

20-year-old game) was a game

called

Henry's Hoard, which was produced by hacking the code of Matthew

Smith's classic Jet Set Willy and rejigging it to make a "new" game -

obviously without any crediting of, or sharing the royalties with,

original creator/coder Smith.

(A somewhat technical breakdown of how this fact was uncovered can be

found here.)

Developers also sought to get round the

problem of having good ideas by continuing to copy them from arcade games,

except this time by choosing obscure arcade games almost nobody had heard

of, and covering their tracks by giving the games entirely new titles

rather than using the original name with one letter changed. This tactic

was widely used in the 16-bit era by Amiga and Atari ST publishers (Core

Design, of Tomb Raider fame, started out by producing Amiga games like

Car-Vup,

an uncredited copy of Jaleco's 1985 arcade title

City

Connection), but slowly

the practice died out - a process which was accelerated by the growth of

emulation, which made videogames history much more accessible and hence

such ripoffs a lot harder to get away with - and it's very rare these days to

see professional software publishers releasing unlicenced, uncredited

clones of someone else's game.

Or at least, it used

to be.

Ocean's Kongs (1983 and 1986 versions): the games

industry has a brief outbreak of morals.

The growth of

the internet, and the rise of the mobile phone as a device for

gaming, have brought the practice of disinterring old videogame

corpses, painting a hasty disguise on them, and flogging them as

your own work, back to life with a vengeance. The web is awash with

unlicenced clones of other people's games, being sold commercially

by professional publishers without either credit or payment to the

original authors. These aren't games which are a bit similar

to existing titles - we're talking absolute 100% ripoffs of all the

design ideas and gameplay mechanics, with a few cosmetic tweaks

hastily pasted on top in an attempt to justify what is in fact a

straightforward case of barefaced plagiarism. Or, if you want to use

the more common term for the unlicenced commercial use of someone

else's intellectual property - piracy.

Unlicenced

clones highlight a curious fact in the attitude of both gamers and

the games industry towards piracy - namely the fact that it seems to

get less offensive to people the more brass-necked you are about it.

For example, take these three diverse approaches to the selling of

other people's games for profit:

- Sell other

people's games for money on a pirate's market stall or a "warez"

website, and the games industry (along with many gamers who've

swallowed some of the industry's endless propaganda and rhetoric on

the subject) regards you as a deadly cancer to be wiped out with all

the force it can muster, setting the full weight of the law against

offenders and gleefully recounting their prison sentences on its

websites.

- Put those same

games on a nice, professional-looking DVD, however, and sell it in a

High Street shop (such as the case of the totally unlicenced "Classix"

CD compilations of old Amiga, Spectrum and other titles which your

reporter unwittingly purchased from his local HMV a couple of years

ago - which actually carried HMV branding on the box artwork - and

which are still openly and illegally sold on the web at staggering

prices, eg £68 for a DVD full of pirated Amiga games), and

you're a respectable businessman who'll be left alone by ELSPA and

their chums to coin in the cash.

- But if you're

really smart, then what you do is completely rip off other people's

ideas and implementation, sometimes even lift the actual graphics

and sound straight out of their games, but present it as your own

work without the slightest credit to the people who actually

invented it. Far from hunting you down with its merciless packs of

lawyers, enforcement agents and Trading Standards officers, the

stupid old games industry won't just let you make profits, it'll

actually give you

awards.

Above: the award-winning 2003 independent game Zuma Deluxe, from

Popcap Games.

Below: Mitchell Corporation's 1998 coin-op Puzz Loop. Spot the

difference.

When World Of

Stuart drew attention to a similar

incidence of for-profit plagiarism in 2003, your reporter was mildly

surprised to see that many coders, as well as a sizeable minority of

gamers, didn't appear to think the cloners had done anything wrong.

Indeed, some indie developers made venomous personal attacks against

your reporter, and some even went so far as to issue violent threats

- not against the plagiarists ripping off other developers' work,

but at the person who'd reported it. (Ironically, when they become

the victims of such behaviour themselves, their view

changes somewhat.)

The actions of the

plagiarists are even more contemptible when viewed in the light of

the coders who work to revive the games of the past in an entirely

more honourable manner. Remake

developers such as Retrospec

and PeeJay's Remakes

spend months at a time recreating vintage games with updated

graphics and sound (and often additional gameplay features), but

rather than claim them as their own work and try to sell them for

profit, they openly admit that they are other people's designs,

produce the games under their original titles, usually obtain the

creator's blessing, and then give the finished work away for

nothing.

Above: Retrospec's beautiful, properly-credited

and free remake of 8-bit classic Head Over Heels.

World Of Stuart

could spend many hours listing only the most blatant unlicenced

ripoffs of other people's games which are currently being openly

sold to PC and mobile-phone gamers by clone publishers as original

releases. However, since it's hard for WoS to name and shame the

guilty without actually advertising their plagiarised products, it

won't bother. The details of the website charging 70 quid for a disc

of old Amiga games, however, have been sent to

ELSPA's Anti-Piracy Unit, so

we'll see if they can find some time in their busy schedule of

persecuting non-profit emulation sites and small-time market traders

to take action against people who've been boldly and openly making

an ostensibly-legitimate business out of it. Keep an eye on WoS for

news of any developments.

You may also like

to watch for the outcome of the recent

lawsuit launched by Sega against Fox/Electronic Arts, the makers

of The Simpsons: Road Rage, a blatant copy of Crazy Taxi which is

still less of a clone than a great many of the "independent" titles

this feature is concerned with. (Sega's suit is actually concerned

with a specific patent rather than general plagiarism issues, but

should it get to court, the judgement could well set a precedent.)

And in the

meantime, if you want to play Puzz Loop on your PC, then buy the

Playstation version - which actually costs less than the PC

clone - and run it on an emulator (because emulators, even though

the games industry hates them and spends infinitely more time trying

to crush them than on trying to stop the commercial plagiarism of

its members' works, are perfectly legal). And you're really

determined to play it illegally, then World Of Stuart recommends

that you go and download MAME and the arcade ROM file, because at

least that way you won't be lining the pockets of a bunch of ripoff

merchants.

|