11 March 2007

|

SCHINDLER'S LIFT

When dreams finally come true.

It's almost impossible now to recall a time when you couldn't get any videogame you wanted. Whether it's importers who'll send the latest Japanese-only console games halfway around the world to you in three days for two quid postage, or filesharing networks offering superior versions of the latest PC games (free of irritating copy protection measures and the user-hostile attitude so often displayed by legitimately-purchased software) within hours of its release in shops (and sometimes before), delayed gratification is no longer an issue for game-lovers.

Yet it wasn't always thus. Back in the 8-bit era, where many "publishers" were in fact some spotty teenager sending out cassette tapes in jiffy bags from his bedroom, and nationwide distribution - far less global - was just a crazy pipedream, countless games fell into the black hole of obscurity.

Now, your correspondent was a resourceful little scamp in the 1980s. Through cultivating friends in the shadier corners of the playground and answering classified ads in games magazines and local papers, it was possible to build up a network of contacts who'd regularly swap C90s full of copied games across the length and breadth of the country.

(Strangely, practically everyone who was a gamer in the 1980s admits to having done this, yet almost nobody - including those same people - will own up to pirating games nowadays. Many of those most vocal in their hatred of piracy apparently didn't mind ripping off tiny independent publishers 30 games at a time, but somehow find it more offensive that anyone might microscopically reduce the profits of vastly wealthy global corporations like EA. Huh.)

In such a way, participants could share the odd and rare titles you'd each somehow stumbled across in the bargain bin of some little local game shop (in those days, no two retailers carried the same range of titles, and chains like GAME were still a decade into the future), or from the warehouse-clearance sellers like Castle Computers who ran double-page ads in games mags, flogging off unsuccessful games at prices tempting enough that you'd splash 50p on something you'd never heard of just because you liked the name. Sometimes someone would even lay their hands on a game that hadn't been released - alert WoS viewers will already remember that without the clandestine Speccy-trading network, gems like Atarisoft's official ports of Moon Patrol and Robotron 2084 would have been lost forever.

But despite such ingenuity, a few titles always managed to slip through the net. Obsessed with conversions of arcade games, especially little-known ones I'd played in backstreet coin-op parlours on annual seaside family holidays in Southport and Bridlington, or only read about in one of my two well-thumbed videogame books, I particularly sought out Speccy clones of things like Turpin, Carnival and Targ. (Games so obscure that when they did get reviewed, as with Carnival, none of the reviewers even realised they were reviewing an arcade port.)

Often, after months and years of searching, the results would be disappointing (Carnival, for example, was almost flawless in graphical and gameplay terms, but had been inexplicably spoiled by the replacement of the coin-op's classic calliope music with a warbly and horrible new tune), but youthful hope is a hard thing to extinguish, and the quest for arcade perfection would go on. Over the years I tracked down most of the Speccy's arcade clones, but the one game I never managed to lay hands on was Jump. An authentic-looking port of Nichibutsu's quirky skyscraper-scaling game Crazy Climber, the only place I'd ever read about it was a review in Crash in October 1984, and since that day I'd unfailingly asked every pirating pen-pal and playground peer if they had it, only to be met with blank looks and shrugged shoulders.

When the Speccy died so did my interest, and it was only this week, while techno-browsing through a bunch of newly-scanned issues of the long-forgotten and much-underrated games mag Big K that a passing mention sent me scurrying off to my Spectrum TOSEC set to see if it was present, or if it was one of the many games still eluding the dedicated sleuthing of the heroic World Of Spectrum detective team. As it happened it was in there (in both its original Spanish incarnation, still titled "Crazy Climber", and the renamed version licenced to Unique for sale in the UK), so it was time to see what I'd been missing for all those years.

Jump is weird from the word go. There's the name, for a start - as noted in the Crash review, why is it called "Jump"? There's no jumping involved anywhere, by you or any of the game's small cast of other characters. It could be a victim of translation, of course - the start screen offers, by way of instruction and scene-setting, "Our friend is a brave climber. You must get that he arrives to the end showing him the way", so evidently it wasn't a professional job - but you'd think someone would have noticed something as basic as the title being the result of some tangled Chinese whispering.

And those aforementioned characters are pretty mixed-up, too - apparently the inlay describes the inhabitants of the towers you're climbing as "apes", and the title screen depicts them as large gorillas. In the game, however, they're unmistakeably human. Crash describes them as "angry-looking versions of John Peel", but what they really resemble is stereotyped Jewish rabbis, complete with skullcaps.

(Perhaps the building is actually an enormous Orthodox synagogue, which would partially explain the inhabitants all looking the same and certainly make more sense than a 40-storey skyscraper being populated entirely by monkeys.)

Adding to the confusion is the fact that the title screen shows you, the climber, as a balding, bearded Semitic-looking type very similar to the dudes in the windows, whereas in the game the protagonist is a clean-shaven little guy with plenty of hair, a lovely patterned jumper and an incredibly tiny head.

The game itself is also a touch backwards. The opening screen is so ferocious that it's by far the hardest part of the game. The ground floors of the tower are jam-packed with furious rabbis heaving bits of furniture (potted plants in the first level, just like the arcade game) out of the windows at you, and the roller blinds which prevent you getting a handhold snapping shut left, right and centre. What's more, when you inevitably get knocked off and plummet to your death (Death? From about 15 feet up?), the game has a nasty habit of putting you back and then immediately lobbing another plant at your head with literally no time to react, so that if you're not already holding left or right as you appear, you're going to die again straight away. So daunting, in fact, is the start of Jump that you may very well wave goodbye to all five of your lives before you've even climbed out of sight of the tower's lobby doors.

Persevere past the beginning, though, and things get a little more manageable. The notoriously tricky twin-joystick controls of Crazy Climber have been well adapted to the Speccy keyboard, with a simplified system that can effectively be reduced to four keys (also enabling you to play the game successfully with a single joystick or pad, if you have a user-definable one), making your climber rather easier to guide around the building than his coin-op counterpart (at the cost of some loss of flexibility - you can't shuffle sideways unless both of your arms are in the "up" position, for example). It's a little slow, but with no music to worry about it's excellently suited to playing on emulator at 2x speed, at which point it's nippy and pretty addictive.

For a Spectrum game it's also very colourful, with the graphics cleverly managed in order to almost entirely eliminate the appearance of the Speccy's infamous colour clash. It's a shame the colours don't change from building to building (you play through four stages before cycling back to the first again, just like the arcade game, but unlike the coin-op all four buildings are the same in both decor and layout), and that there isn't a bit of variety in the inhabitants of the tower (surely they could have found room for three more sprites?), but it's still an impressive visual interpretation of the original game.

I spent a happy morning playing Jump, and even with the weight of 20 years of searching and waiting on its shoulders, it held up pretty well. If it had ever found its way to a wider release, I reckon it would have given a very decent account of itself in the 1984 Speccy market. If you were hoping, after reading all the way through, that this feature was going to end with some kind of dramatic revelatory conclusion, salutary lesson or sparkling insight about something or other, um, there isn't one. I really just wanted an excuse to post that great big screenshot somewhere. I should probably have warned you at the start, now I come to think of it. Sorry about that.

|

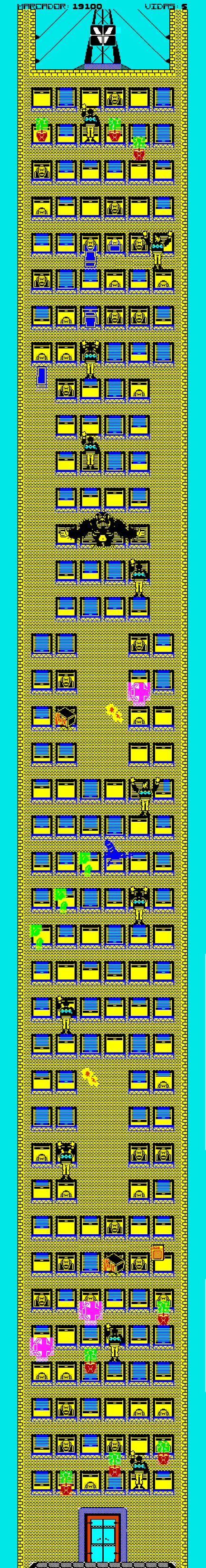

This painstakingly-assembled composite shot of the entire tower shows all the enemy and obstacle types together. in reality the guano-ejecting bird seen halfway up doesn't appear on levels 1 and 3, and the window guys only drop one kind of missile on you per stage. The pot plants and the microwave ovens are easy enough to identify, but what in heck are the blue and purple things?

For lots of extra WoS bonus points, click the image to reveal the full version before it was elaborately resized for maximum elegance of display, and see if you can spot all of the differences between the original and edited versions.

|