|

FAMILIES REUNITED

Stuart Campbell comes

from a long and extremely complicated line of ancestors who

contributed their diverse genes to create and shape the unique

individual that we all know and love so much today. But he’s not the

only one.

It’s easy to get irritable

when idiot videogame journalists excitably acclaim the stunning

"originality" of games which have supposedly appeared out of

nowhere, but about which anyone who knows anything about games knows

otherwise. The most celebrated - if that's the right word - example

of recent years would probably be Worms, recipient of all sorts of

originality awards despite being simply the latest in a 20-year-old

line encompassing scores of previous games which play in exactly the

same way.

(The first example your correspondent knows of is Artillery Duel on

the Colecovision from 1983, but the genre may well go back further

still.)

But sometimes that ire is a tad unwarranted, because some games are

so obscure that it's only by sheer dumb luck that anyone would even

have heard of them, far less be able to identify that they were the

estranged parent or illegitimate child of a far better-known

classic. Count on the dauntlessly diligent descendant-detectives of

Retro Gamer, then, to uncover some of the missing links and finally

gather together some of gaming’s greats and their grand-relatives.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

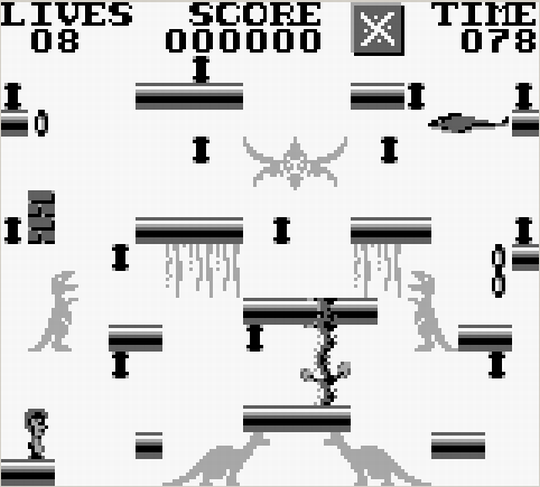

CASE FILE #1 – CHUCKIE EGG

Chuckie Egg is one of retrogaming’s

cornerstones. Alongside the Donkey Kongs, Manic Miners. Stunt Car

Racers and Speedball 2s, Nigel Alderton’s high-speed henhouse

hurry-scurry still represents many people’s ideal for the form, with

its slick controls and non-stop action. Surprisingly few games,

though, have actually replicated its style – not even its own sequel

played similarly, being a comparatively staid and sprawling arcade

adventure. The only game that can truly lay claim to Chuckie Egg’s

DNA is Bill & Ted’s Excellent Gameboy Adventure.

Along with Lode Runner,

Chuckie Egg is a contender for the game to have appeared on the most

formats ever.

Despite this reporter’s single-handed trumpet-blowing crusade over

the last decade, the number of people who’ve heard of this early

platformer for the mono Game Boy is still, taken as an average and

rounded off to the nearest whole number, zero. Which is a tragedy,

because it’s simply one of the greatest platform games of all time.

Comprising 50 single-screen levels spread across 10 worlds, it’s a

riot of invention and pace with something new on almost every stage,

but telltale signs like its speed, ladder-jumping and infinite-fall

ability mark it out as a clear homage to Alderton’s game, with one

of the most obvious tributes being the appearance in World 5 of a

version of Chuckie Egg’s “super duck” (in the form of a flying

stingray) which tracks the player across the level regardless of the

platform structures.

They could quite reasonably

have called this game “Bill And Ted’s EGGS-cellent Adventure”!!!

(Get out – Ed)

Bill & Ted’s EGA takes Chuckie Egg’s ball and runs like the wind

with it, leaving the tiny world of the farmyard behind for the

boundless entirety of time and space, and the gameplay horizons

broaden accordingly. While it never breaks from the basic

run-and-jump-and-collect-stuff template, you never know quite what’s

going to happen on each new level – you’ll be chased through

paradise by relentless angels and teleporting monks, stages will

turn invisible, walls and floors and keys appear and disappear,

enemies pick you up and drop you off the edges of platforms, some

throw boulders or grenades, rabbits roll deadly Easter eggs, other

enemies shoot you with guns or with time-shift bolts that send you

back to the level’s start position, and that’s not the half of it.

Just like Chuckie Egg, some levels are edgy sniping battles where

you pick off a key here and a key there while some are flat-out

headlong sprints, but none will take you more than 30 seconds to

play through once you master them.

But in fact, Bill & Ted’s Excellent Gameboy Adventure is more than

just a de facto Chuckie Egg sequel - it also provides the

missing link between one of gaming’s oldest standards and one of its

newest pioneers. Because with its constant change, instant

accessibility, breathless pace and endless invention and

unpredictability, you only need to continue the logical line from

Chuckie Egg through Bill & Ted and keep going a bit until you

eventually arrive at Wario Ware.

And obviously this guy

should actually be shouting “FOWL”!!!!! (Really,

I’ll have you killed – Ed)

Squished into a tiny 128K cart, Bill & Ted’s had to be endlessly

creative with a very small number of elements. But take away that

restriction – Wario Ware had a whopping 64 times as much RAM to play

around with – and you can refine those levels down from 20 seconds

and 10 seconds to five and three and one, twisting and bending and

distorting them into crazy shapes while sticking to the same

d-pad-and-single-button controls that made Chuckie Egg so instantly

appealing. And you “hen’t” say fairer than that! (That’s it. Get

my gun – Ed)

|

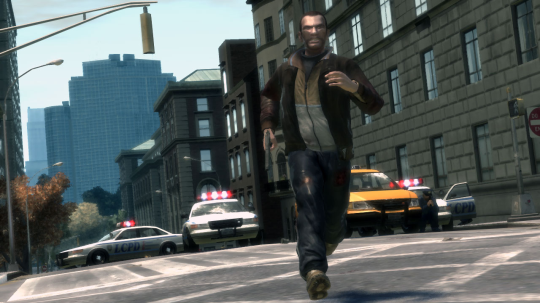

GRAND THEFT

OTOBOKE

You all

know about how Rockstar famously revealed in a magazine

that the Grand Theft Auto games (originally meant to be

more tellingly called Race’n’Chase) were fundamentally

derived from Pac-Man, don’t you? With the obvious

parallels between the overhead-viewed cities of the

original 2D games and Namco’s maze-running classic?

(Interestingly, you were also originally supposed to be

able to choose to play as the police, making the

original GTA the parent in turn of Pac-Man VS - see, the

DNA always makes its way through in the end.)

You do? Splendid. That’ll save us a lot of time later

on.

“Goddammit,

there’s gotta be a power-pill around here somewhere!”

|

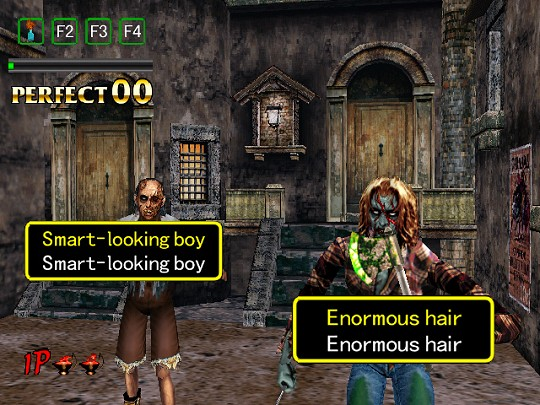

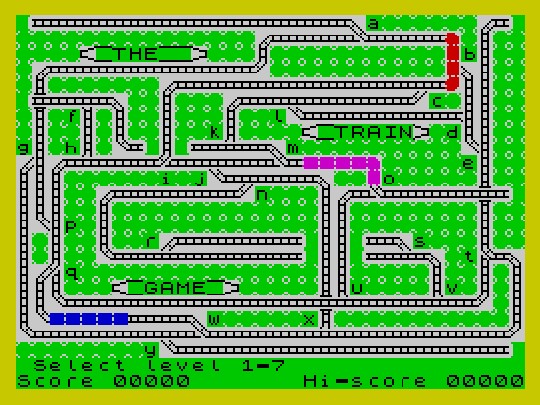

CASE FILE #2 – THE TRAIN GAME

Beyond any rational doubt,

Sega’s The Typing Of The Dead is the funniest videogame ever made.

It's based on Sega's classic arcade light-gun shooter The House Of

The Dead 2, a game which - while cheesy - is also tense, atmospheric

and in parts really quite scary. But by the simple expedient of

replacing your gun with a keyboard and some random words, it

suddenly becomes impossible to be disturbed by even the goriest

assaults, or to react with anything other than a warm chuckle as a

gruesome monster from under the sea jams a trident between your ribs

when you fail to sufficiently quickly type "MAKE ME A HUMBLE

APOLOGY" or "TELL ME A FUNNY STORY" at it to deflect its savage

attack.

But this feature isn't here to talk about how great The Typing Of

The Dead is (which is to say, amazingly great), but rather to

identify its videogaming parentage. And unlikely as it seems, the

only game (other than House Of The Dead 2, obviously) to which TTOTD

owes a genetic debt is a long-forgotten title from the early days of

the Spectrum about points management and maintaining customer

satisfaction on a railway network.

The words

you have to type aren't usually descriptive. We just got lucky here.

Microsphere's 1983 classic

The Train Game wasn't a smash hit even when it only had about 50

other Speccy games in the whole world to contend with. In an age of

the exciting new opportunities offered by the Speccy's

high-resolution colour graphics, the barely-beyond-ASCII visuals

didn't seize gamers' attention, and even those of us still mired in

more medieval times, playing our games on black-and-white bedroom

tellies, couldn't enjoy it either because a large part of the

gameplay was focused on colour-matching the various trains to their

passengers, and telling seven shades of grey apart on a 14-inch

portable was a task of distinctly limited fun potential when there

was Manic Miner to play.

Which is a terrible shame, as The Train Game is completely

brilliant. It's a frantic mix of complex spatial awareness, fast

reactions and multiple forward planning as the player tries to keep

up to a mind-melting four simultaneous trains running around one of

two small railways (there were two different track layouts for the

game, one on each side of the tape), collecting colour-coded

commuters from three stations before they flew into an explosive

rage at being excessively delayed and cost you one of your four

lives (which were also forfeited in the event of trains running into

closed points, crashing into each other, or having points switched

while the train was travelling across them).

The trains couldn't stop (except at stations, and only then for a

fixed brief period), couldn't pick up passengers of other colours

than their own (except the angry ones who'd turned white, who took

precedence over all other passengers and could be collected by any

train, but only at the cost of leaving any waiting passengers of the

train's own colour behind on the platform), and couldn't be

reversed. Each set of points could be set to two positions only,

meaning that if you wanted to make a train reach a certain station,

you'd often have to route it through a long and complex diversion in

order to make it travel in the opposite direction down the line it

was currently on. Oh, and sometimes, at the highest of the game's

seven difficulty levels, a hurtling runaway goods train would appear

and have to be sent into one of the tunnels at the side of the

screen to get rid of it. Man, you kids today have it easy.

The seeming dead ends are

actually tunnels – the one at top right loops to the one at middle

right, for example.

But this feature isn't here to go on

and on about how great The Train Game is (which is to say,

amazingly great), but rather to identify its connection to The

Typing Of The Dead, and your correspondent is sure that the

intelligent, alert readers of Retro Gamer have spotted at least the

obvious half of it already. Off the top of your reporter's

knowledge-filled head, these are the only two videogames ever

created (with the exception of later spinoffs like Typing Space

Harrier, and obviously discounting specifically educational

software) in which the primary gameplay skill is intimate

familiarity with the layout of the QWERTY keyboard. But there's a

bit more to it than that.

Both The Train Game and The Typing Of The Dead, in essence, are not

only about typing skill, but about threat management. Most of the

time, in either game, you'll have two or three pressing problems to

deal with at any given moment, and not only do you have to deal with

them all, you'll have to near-instantly assess their relative

urgency and deal with them all in the right order. In both

games, in fact, it's very frequently necessary to solve one problem

purely to be able to even start tackling the second at all.

(In TTOTD you have to completely finish typing one zombie's phrase

before you can engage the next one, or fight off the projectiles the

first one's thrown at you. Similarly, in The Train Game you'll often

have to route one train through a section of track as another one

bears down unstoppably on the same stretch from the opposite

direction. In either case, prioritise your actions wrongly and

you're buggered.)

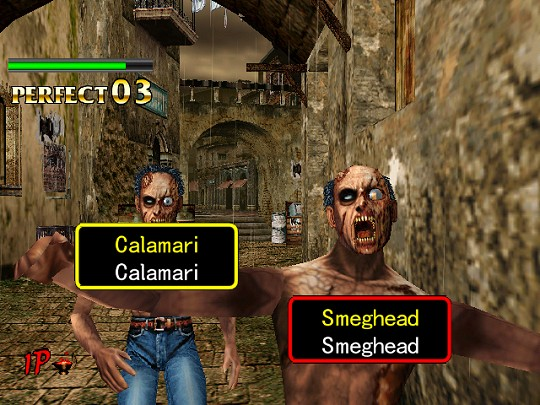

Spook! 'Calamari Smeghead'

was my name when I was in a punk band in the late 80s.

The truth of the matter is

that if you strip away all the surface irrelevance, TTOTD and TTG

are basically the same game. As befits their respective heritages,

The Typing Of The Dead is a little less cerebral and more manic, but

at the higher difficulty levels The Train Game is if anything the

faster-paced of the two, as well as harder and more relentless. Take

on Track B at level 7 and you'll be doing well to last much over a

minute. TTG actually inspired at least one more-obvious clone, in

the form of German developer Kingsoft's superficially very similar

Locomotion for the Amiga in 1992 (a fine game in its own right,

which replaced the typing-based point-switching with

mouse-controlled cursor-pointing), but it's only The Typing Of The

Dead that plays the same way as its parent.

Only one of them's funny, though.

|

TARG-GET MEN

Sometimes

the connections between games are a lot easier to spot,

of course. As long as you're old enough, anyway. You've

got to be a pretty long-in-the-tooth videogamer to

remember Exidy's primitive 1980 coin-op Targ, but if you

are then it's not hard to pick its grandson out of the

ranks of today's high-resolution superstars.

You have to

start a level very poorly to find yourself in this much

trouble.

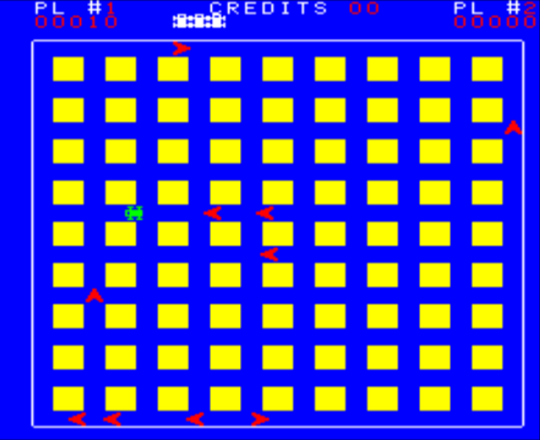

Targ is one

of the simplest videogames ever released. Despite being

set in the picturesque-sounding metropolis of "Crystal

City", every level is an identical grid of yellow blocks

inhabited by 10 red "ramships", whose name gives away

their only attacking capability - crashing into you. You

steer your chunky green "Wummel" truck around, shooting

the ramships and the Spectar Smuggler, a blue cruiser

worth up to 90 times as many points as the ramships but

which only shows up occasionally from a random block of

the city.

Just a few seconds playing Targ, watching the initial

wave of arrowhead-shaped ramships sweep down the screen

in a perfect line, will immediately trigger a sense of

familiarity and recognition in all but the most

unobservant of modern gamers. Can you guess what it is

yet?

Trivia fact!

This screenshot shows the PGR4 version of Waves, not the

Geometry Wars 2 one.

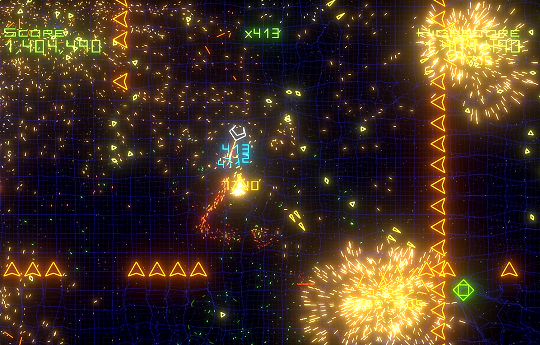

Geometry

Wars: Waves doesn't just share a superficial enemy

shape, axes of movement and mode of attack with Targ,

though those are the most instantly-obvious

similarities. In both games, shooting the main enemies

isn't your real source of points - it's just something

you do to stay alive while you wait for the opportunity

to nail the big rewards, whether that's a Spectar

Smuggler or a juicy clump of score-multiplying Geoms.

(In another little piece of borrowed DNA, Targ

multiplies the scores for ramships as you go on too.)

But the

main common facet of the two games is the extraordinary

addictiveness created by the bone-simple gameplay, in

which despite the almost total absence of intelligence

or sophistication in your enemies (Targ's ramships are

just about smart enough to get out of the way of

a bullet if they see it coming at them from a long way

off, while Waves' denizens aren't even as bright as

that), a single game lasting over a minute is

an epic feat of skill. Since it's hard to accept being

done for by such dimwitted opponents, off you go again

and the next thing you know four hours have passed.

(Waves in particular is a brutal time thief.)

If you

doubt me, fire up Targ in MAME and see if you can beat

the default highscore, which is just 10,000. (Reaching

the fourth screen will just about guarantee that many

points, and the difficulty increases only by a tiny

fraction along the way.) You're going to be there for a

while.

|

CASE FILE #3 – THE PIT

The last game we’re going to look at is

a much-overlooked classic, but one that alert viewers will recall

already having been touched on passingly in the pages of previous

issues of Retro Gamer - Centuri's 1982 coin-op The Pit, the game

that gave birth to Boulder Dash.

(It gave birth to Boulder Dash at the scandalously young age of

two, in fact - the latter game having been released in 1984 -

but let's just skip over that alarming and disturbing paedo-fact for

the sake of decency and move swiftly on.)

Boulder Dash is most commonly associated with the two classic

earth-shifting arcade games Dig Dug and Mr Do, but beyond the

underground setting it has almost nothing in common with either

title. Dig Dug and Mr Do are both fundamentally about battling your

enemies, not negotiating your environment. There are no obstacles in

your way, and the rocks/apples which can fall down the screen are

really there as weapons rather than dangers.

The Pit is different, though. While there are enemy

characters chasing your diamond-hunting miner, they're pretty much

only a distraction. It's perfectly simple for even a

slightly-skilled player to conduct the first few seconds of any

level in such a way (illustrated in the screenshot below) that the

claw-wielding baddies are confined to a small space at the upper

centre of the pit, completely blocked off from anywhere the player

needs to go.

Here you’ve managed to

block off all the pink and blue enemy robots’ paths with rocks (seen

just to the left

and to the right of the central crossroads), and since they lack any

digging ability they can’t get to you at all.

Your problem in The Pit is

- like Boulder Dash - chiefly to navigate your way safely around

each level in order to collect some diamonds and then get out of the

exit without having a rock fall on your head. (Also like Boulder

Dash, you don't actually have to collect all of a level's diamonds,

but there are temptingly large bonuses for picking up more than the

minimum.) There are walls, bottlenecks, rooms and environmental

hazards, as well as the liberal scattering of rocks that constitutes

the core gameplay element of both titles.

The similarities don't end there, though. For one thing, your miner

doesn't just plough through earth like in Dig Dug and Mr Do. To make

a tunnel, he blasts away a square of space with his, um, anti-dirt

laser, then pauses for a moment before moving into the gap. (This is

very much a character-block-centred game, which makes it all the

weirder that nobody ever converted it to the Speccy. There were

unofficial ports to the VIC-20 and the C64 though, one of the very

few advantages of the CBM machines over the rubber-keyed wonder.)

The skilled player, however, can use this behaviour to take out an

adjacent

square of earth and then quickly move off in a different direction,

in a manner very akin to the Boulder Dash trick of holding down the

fire button to dig/push/pick up something without moving into its

space. In both games, it's a subtle play mechanic that separates the

novice player from the expert.

And lastly, there's the behaviour of the enemy characters. The

little grab-robots don't actually chase you - like all the moving

enemies in Boulder Dash, they follow fixed movement patterns (if

there's an empty space below, go down, if you can't go down then try

to go left, etc)

and only kill you if you get very close to them, at which point they

leap on you and smush you. And as in Boulder Dash, they can only

move in existing tunnels - they can't dig their own. And yet despite

all this - their slow pace, limited abilities, lack of weaponry,

rigidly-dictated movement and non-vindictive nature, you'll really

come to hate the little bastards. (Maybe it's the way there's a brief

but violent struggle when one attacks you, a bit like in Maziacs but

with the crucial difference that you never ever win. It looks like a

brutal way to die.)

If you want to see where it all ultimately led, either check out the

superb Boulder Dash Xmas 2002 Edition, which is the finest BD game

ever (playable for free online, with a full-featured downloadable

version for about 11 quid), or Gran Turismo 5. See you next time, viewers!

This innocent first level

might not look exciting, but Boulder Dash Xmas 2002 Edition is the

finest collection

of brilliantly fiendish BD levels since the series was invented. You

can play the full game for free

here.

|

HANG ON A MINUTE -

WHAT?

(“The Pit is basically

the same game as Gran Turismo 5? WTF?" – Bemused reader, Essex)

Ah yes. The thing is, like many parents in today’s

shamefully immoral society, The Pit had more than one

offspring to more than one partner. Y’see, the use of

the phrase “any level” back in the opening paragraphs of

the Pit’s entry is a slight misnomer. The game only has

two different screens - which are actually the same one

except for rock placement - which alternate at

ever-increasing pace until everything happens at

blinding speed and becomes as much a test of memory as

reflex. The enemies are largely incidental, pursuing

their own path regardless of what you do and only

causing you trouble if you actively collide with them.

Sound

familiar at all?

The Pit is all about racing the same circular courses

(you start and finish in the same spot) over and over,

doing “laps” around them until you find the line that’s

both fastest and avoids the pre-programmed enemy AI. As

it goes on, you know exactly what to do and when, but

sometimes your fingers just aren’t quick enough or

co-ordinated enough to perform the actions your brain’s

telling them to. Sometimes you panic and crash into an

enemy because you’re short of time. Sometimes one

mistake will force you to significantly amend your route

and improvise a new ad hoc one, as it brings you

perilously close to opponents you should have avoided.

It doesn’t look like a driving game, but in every

meaningful sense that’s exactly what it is, and in

particular highly rigid and technical ones like the GT

series.

I don’t know if

I can stay awake long enough to write a caption for this

pictZZZZZZ.

Videogamers have a lot of

trouble with this concept, but in fact it’s really what

this entire feature is about. No matter what the

onscreen graphics depict, the simple mechanical fact of

playing ANY videogame is that you’re pressing left and

right and fire to move blobs of coloured light around a

screen. It doesn’t matter if the game world nominally

exists in two dimensions or three, whether you’re

viewing it from above or to the side or out of your

character’s “eyes” or whatever – you’re still just

pressing left and right and fire on the joypad to move

the lights around. To an observer who’s standing behind

your telly, you appear to be doing the exact same things

no matter whether you’re playing Tetris, Pac-Man, Call

Of Duty 4 or Broken Sword: Shadow Of The Templars

Director's Cut, and that’s because you are.

Fundamental gameplay concepts have nothing to do with

either graphical style or game setting. It’s hard to

imagine two more diverse things than, say, the story of

Noah preserving the world’s animal species in the Ark

and a heroic soldier invading a Nazi fortress to kill a

massive cyborg Hitler. Yet the exact same game engine

and gameplay concepts were used for both Super Noah’s

Ark and Wolfenstein 3D on the SNES. They’re basically

the same game dressed in different clothes, and it

shouldn’t take a big mental leap to grasp that that

simple fact – which is pretty obvious in the case of

Super Noah's Ark

and Wolfenstein - also extends to relationships between games

that appear to be a lot less similar to each other.

Don’t let your eyes fool you, chums. If you ever want to

truly understand games, be they retro or ultra-modern,

you really need to get your heads round that idea.

Also, of course, The Pit is a lot more fun than

Gran Turismo.

Feeding animals

on a boat: a lot like shooting Nazis in a castle.

|

|