|

THE DRIVING GAMES BIBLE

The

history of driving games is an unusual one. Whereas most genres follow a

linear evolutionary path, becoming steadily more complex and more

technically impressive with time, driving games are different. Driving

games started in 3D and then went backwards to 2D for several years.

They started off quite technically realistic and demanding, then went

backwards and became more simplistic and easier. Graphics got prettier,

more colourful and more dramatic, then went backwards and became greyer

and duller, and so on. We needed someone intimately familiar with the

idea of going forwards then backwards to chart it all, so obviously we

called Stuart Campbell.

Konami’s 1986 coin-op WEC Le Mans, which isn’t mentioned anywhere in

this feature.

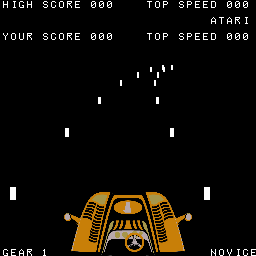

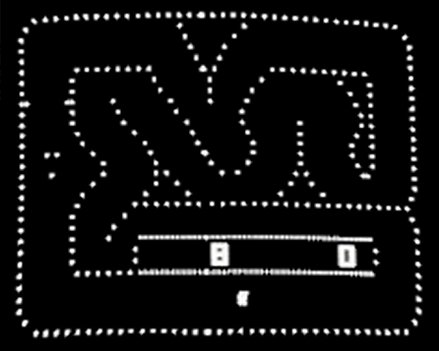

The first instance of driving a car in a

videogame was on Atari's 1976 classic Night Driver. A black screen

faced the player, decorated only with a series of short white posts

disappearing into the horizon to produce an eerily convincing

sensation of 3D. Speeding through the moonlit world at the kind of

game velocity the hardware could impart by, essentially, having no

graphics (even your car’s bonnet was just a plastic sticker attached

to the monitor), you couldn't afford to take your eyes off the

screen for a second.

Steering wheels were next seen in

videogame parlours on the Sprint series of overhead-viewed circuit

games, starting with Sprint 2 in 1976, confusingly followed by

Sprint 4 and Sprint 8 in 1977 and finally Sprint 1 in 1978. The

numbering doesn’t denote sequels - although the various games did

have different tracks - but the number of players. Sprint 8,

impressively, was therefore for eight players simultaneously, all

squished around one fairly normal-sized machine and making arcade

owners swoon with happiness.

To compensate for the lack of human

opposition, Sprint 1 does a remarkable and unique thing: the tracks

change while you’re driving. One minute you’re zooming round

a nice simple loop, then without warning the entire course switches

to a complex crossover route, and then a few seconds later morphs

again to a zig-zag collection of long straights, and so on. If

you’re not expecting it – and why would you be? – it’s hugely

startling and scary.

Night Driver - in fact, not even nearly the first driving

videogame. Fooled you! Ha ha!

Night Driver and Sprint both had purely

demarcative graphics – that is, wholly abstract lines and dots which

served only to mark the distinction between the traversable course

and the “walls” marking the limits of where you could go. The first

coin-op driving game to feature actual graphics in the sense we

understand the term today (that is, depicting some sort of actual

scenery) was Atari’s 1977 release Super Bug, which gave the player

an identifiable vehicle (a VW Beetle) some dense woodland to drive

through. Super Bug also saw the first introduction of “realistic”

handling – in addition to having to cope with manual switching

through four gears (something not seen in arcade games in the

following 30 years), your Bug is prone to drift, fishtailing like

crazy if you go round corners too fast. It’s an incredibly demanding

game which will leave the most dedicated modern racing fan weeping

in a corner within minutes.

Not satisfied with that, though, Atari

followed Super Bug up with the conceptually similar Fire Truck the

next year (which despite still being in greyscale also saw a

significant aesthetic improvement, with the graphics now depicting

an identifiable and rather attractive, albeit somewhat Lego-ey,

suburban landscape with houses, lawns, trees and parked cars).

Fire Truck was the first - so far the

only - co-op driving game, and saw two players charged with steering

a single fire engine through the scrolling overhead course, with one

of them driving the cab and the other trying to keep the trailer

under control. (There was a later single-player version called Smoky

Joe.) It’s absurdly difficult, and almost certainly the most

technical driving game ever created, making a mockery of Gran

Turismo fans and their fiddling with wheel balancing, brake

adjusting and grocket fondling. Only when you can complete a

90-second Fire Truck run without a crash can you consider yourself a

truly skilled pretend driver.

(Atari had also put out another highly

technical and very different coin-op driving game in 1977, the

bizarre side-on precision-gear-shift-timer Drag Race, but that

turned out to be something of a genre dead-end.)

|

TOP FIVE

The

building blocks of the modern racer

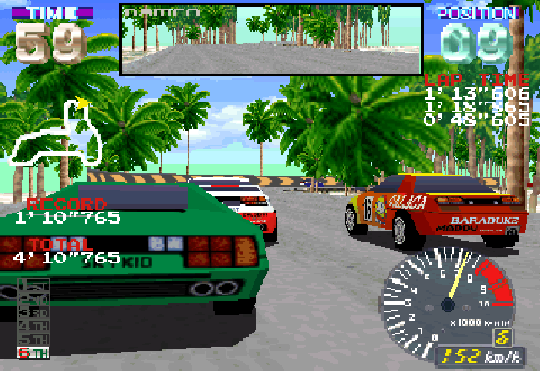

New-fangled high-definition Ridge Racer is very pretty

and all that, but

sometimes I miss the old candy-cane primary colours of

the original.

Ridge Racer 2

Probably the first

game that modern gamers would recognise as a racer of

the sort we play today, the original Ridge Racer

slightly predated Daytona USA and is also a far better

game. However, you can’t argue with a sequel that's

basically all the best bits from all the RR

games put together with better graphics, and that’s what

you get in the monstrously inaccurately-named Ridge

Racer 2.

The only downside - shared with big-brother

titles RR6 and RR7 - is that it starts off terribly easy

where the original was challenging from the off, but

then with only one-and-a-half tracks the original HAD to

be. There’s such a crazy amount of content in RR2 that

it can afford to give a big chunk of it away cheaply at

the start to lure in the beginners and develop their

skills for the stiffer challenges ahead. With the

possible exception of Burnout 2 (see below), simply the

most complete road-racing game of the modern era.

In the early days, Suzuka’s spectator facilities were

sparse.

Pole

Position 2

The first Pole

Position was a phenomenal success, and the sequel

actually did rather less well. However, it was a very

influential pioneer in a very specific field, namely the

inclusion of multiple real-life racetracks. PP1 had

dipped a toe into the water with a pretty authentic take

on the Fuji Speedway course in Japan – the first time a

real-world track had appeared in a videogame - but PP2

offered four selectable courses all based around

real-world race venues, adding recognisable versions of

Indianapolis (a simple oval), Long Beach and Suzuka.

Namco extended the

concept with their Final Lap series, which expanded the

roster with interpretations of Silverstone, Catalunya,

Spa Francorchamps and Monaco, and it’s almost as hard to

imagine an F1 game set in fictitious locations now as it

is to imagine one with only one track.

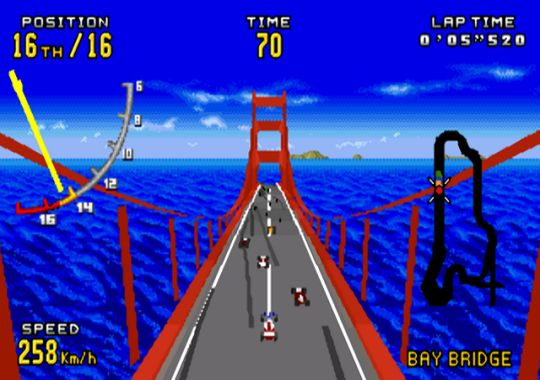

This is a shot of the rather lovely PS2 remake Virtua

Racing Flat Out, which

is well worth picking up on the excellent-value Sega

Classics Collection.

Virtua Racing

Virtua Racing is a

wonderful game, but it’s historically important for

mostly a strange and unfortunate reason. VR offered four

switchable camera positions, the best of which was the

high overhead cam which gives the driver the clearest

possible view of his racing line. But the most popular

was the first-person perspective, something which had

been rare in driving games until that point, and the

high overhead cam was immediately binned for all Sega’s

subsequent arcade racers, perhaps also because of the

extra processing demands it would make when rendering

their more complex, textured scenery.

The side-effect of

that was to destroy, almost overnight, the credibility

of the entire overhead-view racing genre - which till

then had maintained significant success with games like

Super Sprint, Hot Rod, Super Off-Road and Micro Machines

- and focus future driving-game development entirely on

the first-person view. It’s not much of a legacy for

such a great game, but history can be cruel.

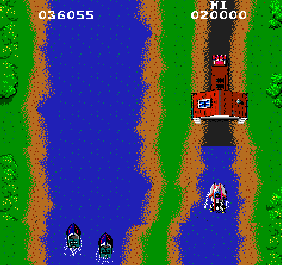

Spy Hunter: also the pioneer in the classic ‘Drive a

motorboat into the

back of a truck parked in a shed and turn it into a

sports coupe’ genre.

Spy

Hunter

Bally’s 1983 classic

Spy Hunter isn’t strictly the first racing game in which

you can directly attack your opponents with weaponry –

you could argue, for example, that Namco’s 1980 Rally-X

claims that accolade with its smoke-screens, or that

Bump’n’Jump from Data East two years later deserves it

by enabling you to actually destroy opponents. But in

the sense we understand the genre today, Spy Hunter is

the crucial first ancestor of games like Mario Kart and

Wipeout, where shooting or otherwise interfering with

your opponents is at least as important as overtaking

them. It was remade in 2001, with modest results.

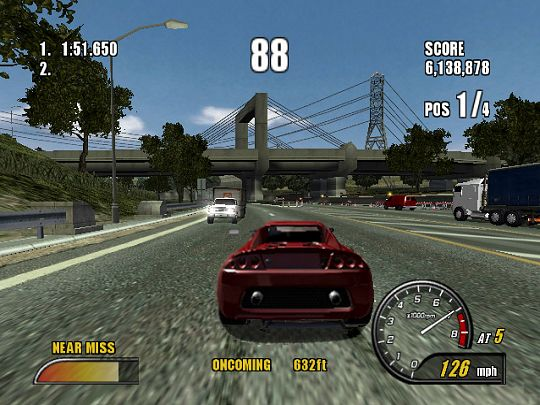

One of the best games, in any genre, of its generation.

Sadly, it was all downhill from here for Burnout.

Burnout 2

Now derived from the

1984 ram-racing template of Bump’n’Jump, The Burnout

series is an excellent example of why someone invented

the phrase “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”. A

franchise which started with a menacingly serious game

of almost Spartan minimalism and toughness is now little

more than a bloated, devalued insult to the intelligence

and self-respect of 11-year-olds, offering up spectacular pyrotechnics

and breathless cascades of medals and trophies to anyone

who can hold down a fire button.

But the second game in

the series is a masterpiece, combining white-knuckle

racing tension with the brilliantly cathartic interludes

of the Crash Junctions. Subsequent iterations would

screw up both elements of this simple genius horribly,

but Burnout 2 strikes a perfect balance between

challenge and reward whether you’re racing or crashing.

|

Arcade technology moved fast around this

time, and by 1980 some pretty dramatic leaps had been made, most

notably in Sega’s legendary racer Monaco GP. (Actually, at this time

the company was known as Gremlin/Sega, no relation to the UK

software house of later years. Whatever happened to Gremlin, eh?)

The first driving game to feature variable terrain, Monaco had icy

roads, rain puddles, bumpy gravel tracks, narrow bridges and

fantastic tunnel sequences where you could only see cars caught in

the narrow conical beam of your headlights, all depicted in glowing

full colour. (Monaco’s modernist graphical style still looks pretty

good today, and the game was remade for the PS2 a few years ago.)

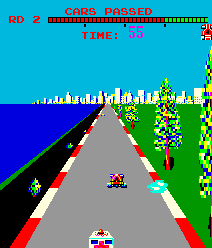

Monaco’s unofficial sequel Turbo (1981)

saw the debut of colour 3D graphics in driving games. Innovatively

used to hide enemy cars in dips in the road, the 3D effect was

pretty solid, but it by no means sounded the death knell for 2D

racing – countless overhead-view vertically-scrolling driving games

would continue to come out for several more years, though mostly

occupying smaller, quirkier corners of the market. It was the next

3D title, however, that would properly sow the seeds of racing games

as we know them today.

LEFT: Pit-lane groupies were much classier in 1980. RIGHT: Turbo

included the dangerous speeding ambulance as a wee tip o’the hat to

its predecessor, and also introduced classic racing-game staple, the

coastal highway.

Namco’s 1982 hit Pole Position is a

classic driving game in its own right – fast and slick with big

colourful graphics and a memorable track based on the real-life Fuji

Speedway - but it introduced a fundamental design change that made

it extra-popular with arcade owners and helped it become a

ubiquitous worldwide smash.

Pole Position was the first coin-op

racing game with a defined ending that would be reached even if you

drove flawlessly (previous games theoretically went on for ever if

you didn’t crash), putting an upper limit of about five minutes on

game time (a big draw for operators in the early 80s, when experts

had honed their skills on games like Asteroids, Pac-Man and Defender

to the point where they could play for hours and hours on a single

credit). Handling was still pretty basic – only two gears and your

car could take the tightest bends at full speed without skidding,

but Pole Position is nevertheless the grandaddy of every modern

racer, and would be the dominant influence on driving games for many

years.

The next few years were quiet in terms

of significant developments, but 1986 would turn out to be one of

the biggest watersheds in driving-game history, with banner releases

in every area of the genre, most of them coming from Sega in a

sudden determined effort to corner a market it hadn’t had

significant presence in since Turbo. For 2D fans, it knocked out a

shameless Road Fighter (see THE FORGOTTEN ONES boxout) ripoff - the

long-forgotten Space Position - and there were motocross thrills in

the shape of Enduro Racer, a distant ancestor of Sega Rally. But the

big news, of course, was Out Run. Building on the sprite-scaling

technology of the previous year’s minor motorbike hit Hang-On, Out

Run blew arcadegoers away with its beautiful graphics, varied

scenery, branching routes, evocative music and (let’s be honest

here) rather mediocre driving model.

"I

told you we wouldn’t turn into a speedboat if we just drove

into this at top speed, you moron."

1986 wasn’t done yet, though, and

veteran coin-op racing specialists Atari struck back with Super

Sprint, a remaking of the very first driving game, Gran Trak 10 (see

GENESIS boxout). With stunningly crisp graphics, subtle additions to

the basic formula (shortcuts and handling-enhancing powerups bought

by picking up spanners from the track) and three steering wheels

bolted to the front for multiplayer action, it was a huge success

and a sequel, Championship Sprint (basically the same game with new

tracks) followed in arcades the same year.

Super Sprint revived the entire dormant

overhead single-screen circuit racing sub-genre, and later years

would see derivatives like Indy Heat, RC Pro-Am, Badlands (itself

the first modern-style battle-racing game) and in particular the

immortally-titled Ivan “Ironman” Stewart’s Super Off-Road generate

more big hits for Atari and others. Countless clones in arcades and

for the 8-bit home micros (including at least half-a-dozen from

Codemasters alone) also laid the groundwork for the evolution of the

genre into scrolling games like Supercars, Hot Rod and ultimately

the much-loved Micro Machines. (For an excellent modern descendant

of Super Sprint, try the wonderful download title

Pixeljunk Racers on PS3.)

|

THE FORGOTTEN

ONES

The most important driving games you’ve never heard of

So few games nowadays ever feature the instruction ‘Go

to church’

SUBJECT: Kamikaze

Cabbie

FROM: Data East (1984)

Fully a decade and a

half before Crazy Taxi was released to massive acclaim

and success, someone had already published the game and

been roundly ignored for their trouble. Kamikaze

Cabbie’s gameplay is almost indistinguishable from its

popular descendant – the large city you can roam around

freely is there, the core “find a passenger and take him

where he wants to go” concept is the same, and it’s even

got the big arrows to tell you the way. You can get away

with bashing other vehicles around, and the fare tips

according to how fast you get him there.

It was a

massive flop, but the authors must have at least gotten

a bit of a warm glow 15 years later from the knowledge

that someone had been watching.

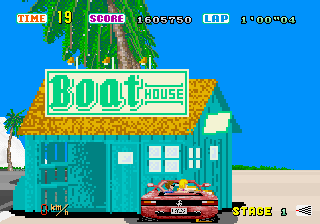

Road Fighter also inspired Out Run’s scenic themes, with

deserts

and towns to speed through as well as the classic beach

road.

SUBJECT: Road

Fighter

FROM: Konami (1984)

Alert readers of our

splendid sister title Retro Gamer will already know

about this one, but the word needs to be spread. Road

Fighter is absolutely brilliant in its own right, and

also unique as the only pure-racing coin-op ever to be

controlled with a joystick rather than a steering wheel.

More importantly in this context, though, it pioneered a

feature which it’s impossible to imagine driving games

without now, but which was a first in its day – drift

control.

Crash into another car

at high speed in Road Fighter and you don’t simply

explode (as was the fashion of the time), but bounce off

and start sliding across the road. The only way to

regain control before you plough into the walls and blow

up is to steer INTO the skid, just as you’d do in a real

car but the complete opposite of a gamer’s intuition.

It’s a small step, but it created the most fundamental gameplay mechanic of every driving game today that’s got

drifting in it, ie all of them. Ridge Racer, Daytona,

Outrun 2006, Race Driver GRID – every one of them owes a

debt to Road Fighter.

Impressively, Stocker even left tyre tracks in your wake

as you took reckless shortcuts through people’s gardens.

SUBJECT: Stocker

FROM: Sente (1984)

The most successful

racing-game franchise nowadays is the Need For Speed

series, blending fast racing thrills with a seedy crime

backstory full of stereotype “outlaw” characters with

interesting haircuts. But its roots lie in a bizarre

little arcade game born a decade earlier, which was the

first racer to concern itself with zooming across the

country outrunning the police.

Stocker (in which you

traverse several states, free to take shortcuts across

terrain and alternate routes) led directly to Test

Drive, which in turn led to Titus’ 16-bit cult classic

Crazy Cars 3 (introducing most of the character/story

elements), which is the most recognisable ancestor of

NFS.

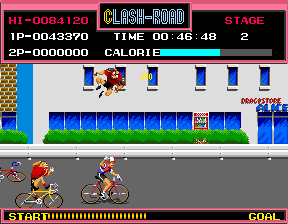

I’m

slightly more concerned that we’re all cycling to

‘Dragstore Alice’ than by the brutal road rage, frankly.

SUBJECT: Clash-Road

FROM: Woodplace Inc (1986)

Side-scrolling racing

games are a surprisingly rare beast, even in the

earliest days of gaming. There are only a tiny handful,

and almost none of them involve cars – you can have

motorbikes (Excitebike, Super Bike, Motocross Maniacs),

people (Metro Cross) or even scrawny desert birds chased

by wild dogs (Road Runner), but with the exception of

Atari’s early Drag Race game makers seem to have

something against side-viewed racing on four wheels.

Rarer still are games set on bicycles, but the

incredibly obscure Japanese outfit Woodplace not only

came up with a side-scrolling bike racer, but also

secretly invented one of the most famous series in

gaming, EA’s 1991 Road Rash.

Clash-Road (who wants to bet that EA’s game was

originally called “Road Clash”?) is a misleadingly

sedate-looking affair accompanied by a twinkly little

calliope tune, but it nonetheless bleeds violence from

every pore.

As you pedal along some lovely town and countryside

roads, you wreak carnage everywhere you go, punching out

at your opponents to knock them into roadside obstacles,

concrete barriers, holes in bridges and more. Joggers

and wildlife aren’t safe from your cycle-path psychopath

either, gaining you bonus points and energy if you mow

them down. You can be sure that the protagonist of this

game grew up to live in Liberty City.

|

1987 was mostly a year of consolidation,

with sequel releases like Super Hang-On and Turbo Outrun, along with

Namco’s spiritual successor to Pole Position, Final Lap. The most

notable release of the year was Taito’s Full Throttle, a game that’s

such a staggeringly, breathtakingly blatant ripoff of Out Run that

it’s a wonder Yu Suzuki didn’t get all his mates together, go round

to Taito and kick their heads in. However, it’s also clearly the

skeleton that would later be fleshed out into Chase HQ, so there was

a glimmer of redemption on the horizon.

The next great leap forward for the

driving game wasn’t far away, though, and in 1988 it arrived in the

shape of Hard Drivin’. One of the most genuinely groundbreaking

releases of all time, Atari came up with the first ever proper

driving simulation and also introduced the first ever true polygon

3D, amid many other innovations. Your car had four gears (for the

first time since the mid-70s), a complex functioning dashboard, a

force-feedback steering wheel and an ignition key, and you could

wander freely around the game area exploring the two different

tracks (Speed and Stunt, with its iconic loop-the-loop) to your

heart’s desire, even turning around and driving the course backwards

until your time ran out if you felt like it.

There were action replays of spectacular

crashes – another first – and the game remains practically unique

apart from its own sequel Race Drivin’. (Two more sequels were

produced but never released.) It didn’t get a halfway-decent home

conversion until its 2004 appearance on Midway Arcade Treasures 2

(Xbox, PS2, Gamecube), but finally now everyone can sample its

absolutely uncompromising brutal difficulty for themselves. After a

couple of laps of Hard Drivin’, controlling a real car is a piece of

cake.

While home formats of the time couldn’t

come anywhere close to the power required to run it, Hard Drivin’

(along with another Sega sprite-scaler, 1988’s Power Drift by Out

Run designer Yu Suzuki) did provide the raw genetic material for

Geoff Crammond’s legendary Stunt Car Racer in 1989. SCR remains one

of the most fondly-remembered titles of the 16-bit era (though it

was also ported successfully on 8-bits) and still occasionally

inspires new games like the excellent

Gripshift for the 360, PS3 and PSP. It was Crammond’s next

title, though, that three years later would go on to exert a

profound and lasting influence on the direction of the driving game

genre. That game was Formula 1 Grand Prix.

It

might not look like much nowadays, but in 1992 F1GP blew everyone’s

socks off.

Taking the simulation ball from Hard

Drivin’ and sprinting off over the horizon with it (stopping only to

pinch a few bits from Indianapolis 500, a 1989 Electronic Arts title

that was the first true simulation of a real-world race event), F1GP

was an exhaustively detailed sim, including accurately-mapped

renditions of all 16 of the F1 tracks of its day (Indy 500 had just

a single oval loop) and dozens of authentically-detailed cars.

But it was its driving model that

captivated players by the thousand – realistically complex and

demanding with endless possibilities for fiddling with the car’s

setup, the game offered you as much help with braking, accelerating

and steering as you wanted until you got used to the challenge of

controlling the car unaided, a system that’s been copied by every

“serious” driving game since. It was quite simply a masterpiece of

design and implementation, made all the more astonishing by being

essentially the work of a single person. Every F1 game of the last

17 years is basically just this with better graphics.

1992 also saw the release of another

driving game every bit as influential as F1GP (and even more

successful), but which couldn’t have been any more dissimilar to it.

Super Mario Kart came out of nowhere, a seemingly-throwaway spinoff

release which appeared fully-formed with barely a note of fanfare

but went on to become one of Nintendo’s most valuable bloodlines.

Knocked together so quickly it doesn’t

even have a proper single-player mode (solo racers still have to

drive around in a split-screen letterbox, with half the display

wasted on a near-useless map), SMK was nevertheless a runaway hit,

helped by not only being able to race a friend on the normal

grand-prix tracks but also in a brilliant balloon-popping deathmatch

game that’s never been bettered by any of the many sequels. (Other

titles in the series have notably better single-player courses and

play mechanics - particularly Mario Kart 64 – and have permitted the

participation of many more players, but none have ever approached or

even simply replicated the genius of SMK’s deathmatch game.)

|

THE ICONIC

CHARACTER

Reiko Nagase (Ridge Racer Type 4)

Racing games are one

of the few remaining genres where (with the exception of

the Need For Speed series and a handful of others) the

player predominantly plays as themselves, rather than as

a predefined character in a story. As a result,

characters are rather thin on the ground – if anything,

the cars are the stars. But nobody wants to read 600

words about the Nissan Skyline (nobody who doesn’t

urgently need drowning in a bucket, anyway), so instead

we’ll seize on the chance to get a bit of eye candy in.

Ironically, of all the

Ridge Racer games, Type 4 is the only one that IS

burdened with something approaching an ingame plot, but

it’s got nothing to do with “Reiko Nagase”, a made-up

lady whose only job is to add a bit of class and glamour

to the intro. She pulls it off memorably in one of the

very few videogame opening scenes worth watching, 100

seconds of sheer soft-focus genius which deftly and

wordlessly encapsulates the entire ethos behind Ridge

Racer.

Indeed, so perfect is

RRT4’s atmosphere-defining introduction that when

imaginary Reiko was dumped in favour of the

equally-unreal “Ai Fukami” for Ridge V (Reiko actually

first appeared in Rage Racer, but without any kind of

story), fans made such a fuss that she was brought back

for 6 and 7.

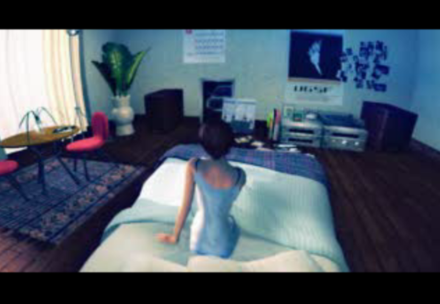

We first meet Reiko

sitting up in bed in her immaculate,

tastefully-minimalist apartment. She appears to be a

young secretary (according to Namco’s subsequent

“biography” she was 23), and we next see her apparently

heading off to work through a rundown-looking industrial

dockland area.

All this is designed

to make Reiko look tiny and delicate and serene, and

accordingly is shot with very static cameras, but is

spliced with furious, fast-cutting action-movie images

of high-octane racing, with huge metal cars thundering

down the track, smashing into each other and the

roadside barriers and flying off the tarmac into the

air.

The deliberate

contrast between the fragility of little human Reiko and

the brutal machinery of the racing cars is further

emphasised when, as she passes some towering skyscrapers

and walks on through one of the trademark Ridge tunnels,

the heel snaps off one of her shoes. (It’s such a nice

day that she seems to have spontaneously decided to

eschew the daily grind of work and head off towards the

coast, which in Ridge Racer games is always conveniently

close to the city.)

She rolls her eyes and

continues walking, now on the road itself, as the

coastal highway has no pavements. Hobbling along with

one shoe in her hand, she cuts an even more vulnerable

figure than before, and suddenly we switch back to the

race and realise, in some alarm, that the cars are

hurtling down the very same road Reiko is walking along.

But our brave heroine,

hearing the roar of approaching engines, doesn’t fret.

Instead, she turns and calmly sticks out a thumb to

hitch a lift.

By now, an especially daring and reckless overtaking

manoeuvre has seen the silver-grey Solvalu 02 barge its

way to the front of the pack and establish a lead. As it

speeds out of the tunnel into the dazzling sunlight, the

driver spots Reiko and slams on the anchors. What’s the

point in winning the race, after all, if you can’t stop

to help out a pretty girl in a short skirt along the

way?

We get a view from the driver’s seat, catching a glimpse

of his reflection in the passenger window. The driver,

too, is a faceless machine-like being hidden behind a

helmet and driving suit, but the reflection disappears

as the electric window winds down, first revealing the

sparkling ocean, then Reiko as she approaches in the

wing mirror, and finally her face as she leans in

hopefully.

She flashes a sweet,

heart-melting smile and then we see her feet – one

shoeless, slight and exposed between the hard steel of

the car and the hot, unforgiving tarmac – as she climbs

elegantly in. There’s still no sign of the other racers

as the Solvalu gets back under way, cresting a hill with

just the ocean and the horizon in sight.

Shortly afterwards, we

see it rocketing over the familiar finish line - raw

power and unspoiled beauty fused together in the spirit

of optimistic, soulful humanity that sets the RR series

apart from its ugly, macho and joyless competitors - as

the screen fades to black and the opening greeting

flickers into life.

“Welcome to the world of Ridge

Racer.”

|

With occasional exceptions like Mario

Kart and successful series like the Lotus Challenge games on the

Amiga and Atari ST, driving games on home formats were still fairly

rare in 1992, as even pseudo-3D racing stretched the hardware of the

era to its limits. The arcades, though, posted notice of what was to

come with the release of Virtua Racing, Sega’s magnificent and

groundbreaking true-3D classic that took Hard Drivin’s fully-built

and freely-navigable worlds and finally gave them racing speed. It

was the following year, however, that would be the biggest watershed

in the history of the genre. 1993 saw the debuts of Ridge Racer and

Daytona, two coin-op hits which would turn out to be the flagships

of the next generation of home console wars.

The two games have much in common, not

least the exaggerated drift-based handling style that’s almost

ubiquitous now but was still in its infancy at the time. Ridge,

though, narrowly made it to market first, and a frankly incredible

Playstation conversion - put together by a tiny handful of people in

just six months for the machine’s launch - all but strangled the

Saturn at birth. While it actually did very well as a translation of

the coin-op’s gameplay, Daytona Saturn’s atrocious pop-up, crude

textures and iffy framerate were an embarrassment next to the crisp,

near-arcade-perfect PS rendition of Ridge Racer, creating a

perception of technical inferiority that was only partially true but

would hamper the Saturn all its life.

The game, too, has been generally held

by history to be slightly inferior to its Namco rival, as evidenced

by the numerous sequels to Ridge, while Daytona only managed one

(unsuccessful) arcade follow-up and none on home formats. (That's

unless you count the four semi-sequel reworkings of the original

game which appeared on various formats and in various territories:

Championship Circuit Edition, Deluxe, Circuit Edition and 2001,

which between them contributed six new tracks and several other new

features, arguably making them equally valid as sequels as

standalone titles like Ridge Racer Revolution.)

Blue, blue skies in Ridge Racer Revolution, the first of many

sequels to Namco’s all-time classic.

Historians differ on the reasons for

Ridge Racer’s ultimate victory - and indeed in arcades you’re

still more likely to encounter Daytona cabinets, because Sega

far-sightedly concentrated more on installing up to eight linked-up

multiple machines whereas Namco’s flagship was the stunning

single-player-focused “Full Scale” edition of Ridge, featuring an

entire real Mazda MX-5 car for the driver to sit in, which took up

as much space as four Daytonas but only brought in one credit's

worth of money at a time.

Some point to Ridge's much friendlier

drifting model, but the most convincing argument centres around

character. While Daytona has very distinctive, memorable courses,

they’re oddly sterile and soulless, something which can be

attributed to the bizarre near-total lack of buildings in them -

apart from two tiny stretches of Seaside Street Galaxy, there’s

nowhere in Daytona that anyone might live, which is odd for a game

carrying the name of a real-life place.

While RR appears to take place in a real

city packed with skyscrapers, hotels, billboards and petrol

stations, instantly engaging the player in a captivating and

believable environment reinforced by an excitable commentator,

Daytona is set in a ghost world, with bridges and tunnels leading

from nowhere to nowhere and no sign of human habitation except the

disembodied voices singing the famous backing songs, and the game

simply doesn’t create the same emotional bond with the player that’s

sustained the RR franchise for 15 years.)

|

DEFINING MOMENTS

Now this is a terrible maritime disaster waiting to

happen.

A View To A Kill

Game: Virtua Racing

We’ve already

mentioned the unfortunate unintended consequences of

Virtua Racing’s biggest innovation, but it’s hard to

overstate just how thrilling it was in 1992 to be able

to swoop up and down like Superman over the three iconic

VR racetracks. The camera’s lightning-quick,

ultra-smooth zoom-in from the Scalextric-esque

helicopter view to the inside of the driver’s helmet

(quiet at the back, there) and out again was an

intoxicating demonstration of the power and potential of

the coming hardware generation, and nothing can ever

quite match that first high of new experience.

So much so, in fact,

that certain people we know, who shall remain nameless,

spent their whole first credit just marvelling in the

pit lane and completely forgot to actually start the

race before their time ran out.

Excitingly, the Model 2 Emulator is on the brink of

making 8-player online

Daytona a reality, but it’ll never eclipse the sheer joy

of doing it in real life.

Keep Your Enemies

Closer

Game: Daytona USA

No arcade game has

ever generated more multi-player income than Daytona

USA, and that’s because if you can get seven mates all

in the arcade at once, nothing in videogaming comes

close to an eight-player Daytona race. (Which is why you

can still find the huge, space-swallowing eight-cab

setups in big arcades 15 years later – graphics be

damned, people will always pay money for an experience

this good no matter how rough it looks.)

All sitting in

your own majestic cockpit cabinets, the screen shows you

exactly who you’re racing against and exactly who just

sneakily shunted you into the vast, cripplingly slow

grass verge on the huge bank turn of Dinosaur Canyon. If

they’re in the “car” next to yours , the temptation to

just lean out of the cabinet and smack them one in the

face can be almost overpowering.

It’s a shame nobody’s built a real-world version of the

Hard Drivin’ race park you could take your own car

round. The hundreds of deaths annually would be a small

price to pay.

Head Over Heels

Game: Hard Drivin’

If the car in Hard Drivin’ were a real one, the

manufacturers would have been sued into bankruptcy over

its lethally skiddy handling and sloth-like

responsiveness. It would have been dangerous enough to

take it down to the shops to buy some milk, but to try

to get it all the way round a giant concrete

loop-the-loop was positively suicidal.

As the angular polygons struggled to keep up with

spinning the entire horizon around AND convey the

lateral movement of the road round the loop, the first

time you ever successfully came out the other side in

one piece felt like it must have been for Neil Armstrong

when he walked on the moon. The sense of achievement,

coupled with the opening up of a whole new sandbox world

of possibilities, was even more dizzying than the loop

itself.

|

In truth, 1993 marked the end of major

innovation in the driving genre, and everything that’s happened

since has been basically a logical evolution of the gaming DNA that

was already in place by that time. Wipeout on the Playstation, for

example, represented a cultural and economic phenomenon, but in

gaming terms it’s just Super Mario Kart with futuristic graphics.

1995’s Sega Rally created a sub-genre of rallying titles, but the

meaningful differences between it and road-racers like Ridge and

Daytona were largely superficial (and invented by Monaco GP anyway),

although it would eventually develop into the likes of Motorstorm,

where the effect of different terrain becomes so significant as to

genuinely alter the core gameplay mechanic.

(Motorstorm’s other

parent, incidentally, is the 1996 Konami find-your-own-route coin-op

GTI Club, whose lack of a home port was one of the great tragedies

of driving game history until it appeared as a PS3 download game in

2008.)

That leaves us with only two significant

strands of driving-game bloodline left to chart, a pair of close

relations which comprise the two most prominent brands in the modern

genre. The 1997 release on the Playstation of Gran Turismo was half

of a cultural double-whammy that ended the brief Wipeout-inspired

era of console games being seen as hip and cutting-edge in the wider

world of fashion. While lifestyle magazines like The Face had for a

while been dazzled by the Designers Republic stylings and big-beat

soundtracks of the futurist hover-racer, and also by the iconic “girl-power”

figure of Lara Croft, Gran Turismo (along with its spiritual sibling

Final Fantasy VII) swiftly reasserted the jealously-guarded reign of

the traditional obsessive, conservative and socially-dysfunctional

nerd over the world of videogaming.

WipEout – very, very briefly making games cool.

Not so much a driving game as a

simulation of being a pit mechanic and a used-car dealer rolled into

one, GT picked up an oily baton from Geoff Crammond’s F1GP and

distilled it even further, fixating on a strange and

highly-selective definition of “realism” aimed at science geeks with

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder.

(As opposed, that is, to the

replication-by-exaggeration of the adrenaline rush of high-speed

driving that had been the goal of Ridge Racer designer Fumihiro

Tanaka. One of the developers of the PS version recently explained

the concept to our splendid sister magazine Retro Gamer: “Ridge Racer is

different from other companies’ racing games - even for people who

can’t drive in real life, if they play Ridge Racer they get a sense

of how good it must feel to drive fast.” This ethos has most

recently been seen in Sega’s fantastic modern updatings of Out Run.)

In GT, reckless thrillseekers are

immediately discouraged by interminable technical “licence tests”,

bearing no relation to the skills required in actual races, before

they’re allowed to enter one at all. Yet conversely, the game inflicts only the

smallest of penalties for smashing into opponents at 220mph. Go

figure. Tracks,

too, are largely identikit grey professional circuits, with a few

more-exciting street courses grudgingly thrown in for a bit of

variety.

|

GENESIS

Gran

Trak 10

Later reworkings of the Gran Trak design, like the

Sprint games,

featured much wider roads and less punishing track

design.

Alert

viewers will of course know that the start of this

article is a great big fat heap of lies designed to

catch out trainspotters who only read the first

paragraph then send in angry letters of complaint.

The REAL first videogame driving experience ever actually happened in

1974, when Atari released a game called Gran Trak 10.

One of the first wave of arcade games, which actually

operated via dedicated solid-state electronic circuitry

rather than on ROM chips, it’s long since been forgotten

by gaming history.

It

looked a lot like Sprint, but with a single more complex

track, and there were no CPU opponents – you simply

raced against the clock until time ran out, with only

oil slicks and the track walls as danger.

The company released

several other pre-Night Driver driving games on the same

sort of technology, including the scrolling Hi-Way, Indy

800 (an eight-player game similar to the later Sprint 8)

and the peculiar demolition derby Crash’n’Score, as well

as a two-player version of GT10 called Gran Trak 20,

which have all suffered the same fate – there are few if

any surviving examples of the original machines, and the

solid-state design means that none of the games are ever

likely to be emulated.

To all intents and purposes, then, none of them can be

meaningfully said to exist, and history starts with

Night Driver.

|

But the world comprises more dullards

than superstars, and accordingly the GT series has shifted close to

50 million copies across the globe so far, not counting the

suffocating hordes of less-accomplished clones it also inspired

(even getting one into arcades, in the shape of Sega’s 1999 uber-sim

Ferrari F355 Challenge). But one game which attempted to merge GT’s

nerd appeal with the character and exhilaration of Ridge has been

almost as successful, at least in terms of reaching its potential

audience.

Metropolis Street Racing arrived on the

Dreamcast in 2000, and applied realistic driving physics and

real-life cars to a game not only set in glamorous and

accurately-mapped real-world city streets, but which also rewarded

the player for irresponsible show-off stunt driving. (Another

example, incidentally, of the influence of GTI Club.) Escaping the

bonds of Sega’s doomed console for the Xbox and undergoing a name

change to Project Gotham Racing, the series went from strength to

strength, and offers car geeks a slightly more exotic and expressive

way to indulge a borderline-autistic collecting mania. (Whoever said

that GT and PGR were basically Pokemon for slightly older gamers was

a wise sage indeed.)

And that’s pretty much it for now. Every

driving game of the last decade or more has been derived - with

varying degrees and elements of crossover – from half a dozen basic

part sets, namely Ridge Racer, Out Run, Wipeout, Crazy Cars 3, GTI

Club and F1GP, and there’s little sign of that changing in the

forseeable future, despite about one game in every three released

for the major consoles being a driving title of some sort or

another. Perhaps only an unlikely flop for the (sort of) imminent

(ish) GT5 could cause a real shake-up in the status quo, and it’d

take a brave man indeed to predict that.

|