|

WORTH A THOUSAND WORDS

The Art Of C&VG

Last month’s The

Definitive Frogger left even RG’s dedicated historian Stuart Campbell’s

with a brain so broken that he couldn’t face doing any complicated research

this month. So we gave him some nice pretty pictures to look at instead.

The magazine you hold in your hands,

viewers, is the last of its kind. Now, don’t panic – Retro Gamer

isn’t about to close down. (Or at least, if it is nobody’s told me

about it. Come to think of it, where IS last month’s pay cheque?)

But there’s something RG does, that used to be enormously

commonplace, but which no other videogames magazine has done for

years. Can you guess what it is? See if you can figure it out before

I tell you, which will be in about three paragraphs’ time.

Most of the publications you’ll find

on the videogames shelf at your local newsagents aren’t “magazines”

in the traditional sense of the word at all – they’re glorified

sales brochures, produced by people who quite openly see themselves

not as the servants of their readers but as extensions of the games

industry’s PR sector. (Almost the entire writing staff of one

widely-respected current title, for example, resigned a few years

ago when they were told by their own management, among other things,

that they couldn’t give games published by Sony review scores lower

than five out of ten.) By comparison, 25, 15 and maybe even 10 years

ago, games mags were primarily a hobbyist affair, written for (and

by) a community of dedicated enthusiasts as the only means of

sharing information about their common pastime.

Because most game publishers were tiny

little companies operating out of someone’s back bedroom or a flat

above a chip shop, there were no big marketing departments around to

either dazzle reviewers with expensive promotional trips to exotic

foreign lands, or bully them with threats of withdrawing thousands

of pounds in lucrative advertising in one fell swoop. Combined with

the absence of the internet - leading to circulation figures on

average two or three times that of a modern games mag, despite the

much smaller total number of gamers in existence – this situation

led to a relative financial stability when it came to planning the

magazine’s budget. So that’s one thing.

Here’s another thing: nowadays, sleek,

glamorous, state-of-the-art publications like Retro Gamer take

advantage of superb modern screenshot technology to produce

beautiful images of games. Whether it’s giant blown-up single shots

or lovely pieced-together maps showing entire gameworlds at a single

glance, it’s easy for us to show you exactly what a game looks like.

Readers (and mag editors) take this technology for granted now, but

in bygone times (even as recently as the early 1990s, when your

reporter first joined the massed ranks of videogame journalism),

things weren’t quite so simple.

Back in those days, publishing was

still largely a physical business as opposed to a digital one, and a

great many magazines still illustrated reviews and the like by the

primitive (and expensive) method of having a photographer point a

stills camera at the TV screen while the game was being played, and

taking a picture of it. It’s difficult on a technical level to

photograph moving images on a TV screen, though, and this method

delivers extremely variable results (especially when printed in

black-and-white, as many games mags still predominantly were

throughout the 1980s), and some publications – one in particular -

chose to find a rather more creative solution to the problem.

If you’re a bit slow, or can’t stand

the tension any more, or just realised immediately on looking at all

the great big pictures splashed all over the place, we’re talking

about custom artwork – and specifically that which was found in the UK’s first

and longest-running (23 years, until it was bought and closed by a

rival publisher in 2004) games magazine, Computer And Video Games.

Once a staple of the videogames

journal, hand-drawn and painted illustrations compensated for crude

1980s graphics and primitive production methods, but also helped to

give magazines like Crash, Zzap and Your Sinclair the individual

senses of character and personality that made them stand out from

each other. In the modern world that loss of character has been one

of the factors causing sales to plummet, as paper publications fail

to cultivate a unique identity that would help give them a selling

point over the fast-moving but bland and corporate world of internet

games journalism.

But the editors of the 1980s would no

sooner have contemplated doing away with custom artwork than today’s

editors would try to live without rehashed press-release “news”,

pre-supplied “interviews”, generic preview “screenshots” taken from

cutscenes, and advertiser-approved “review” scores. (Enough with

the “quote marks” – Ed) Artwork was an intrinsic, obvious and

non-negotiable part of magazine creation, so before we descend any

further into the gloomy abyss of modern mainstream games mags and

get all depressed, let’s take a few pages out of our busy schedule

to celebrate the halcyon days of the videogames illustrator, and

perhaps offer a silent prayer of gratitude that at least one

publication (this one, if you’ve forgotten) is doing its bit to keep

a tiny, flickering flame alive.

------------------------------------------------------

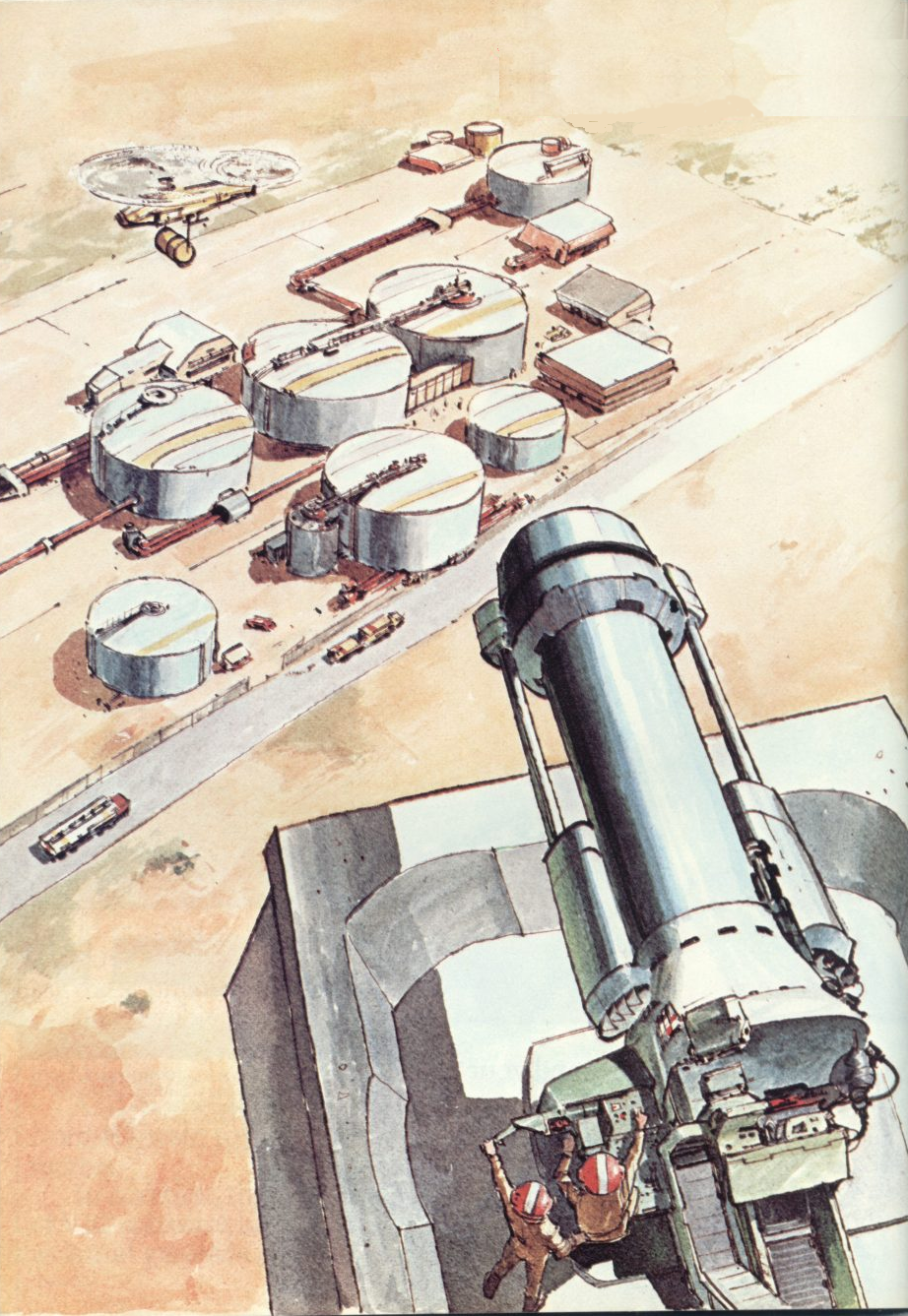

THE POWER OF SUGGESTION

(Part 1)

------------------------------------------------------

As videogames journey ever further

into the Uncanny Valley (the name for the psychological phenomenon

whereby the closer graphics get to photorealism, the more our brain

concentrates on what’s wrong with them, in order to prevent us from

being fooled by fakes), custom artwork takes us on a trip to the

opposite end of the spectrum, where the crudest of all possible

visuals leaves space for our imaginations to fill in a scene far

more evocative than any graphics card could depict. Take a look at

this example from C&VG’s June 1983 issue. It’s the facing page from

a type-in ZX81 program called “Cannon Master”.

The black-and-white in-game graphics

showed you in command of a few arrows shooting minus-signs at

asterisks in a big “U” shape. But thanks to Jon Davis’ illustration,

when you actually played the game your mind saw you perched high up

in the sky above a dusty, windswept desert canyon, manning huge gun

emplacements charged with protecting your army’s vital fuel dumps

against a deadly hail of enemy rockets fired by an unseen enemy. The

game graphics are just placeholders for the mental image, and your

brain fills in the “photorealism” for itself. (If you want to

experience the sensation, I’ve personally typed in the entire game

and saved it as a file for use with ZX81 emulators - you can

download it from the forum of my website at

www.worldofstuart.co.uk.

Let nobody say we don’t go the extra mile for our viewers here at

Retro Gamer.)

-------------------------------

FRONT AND CENTRE

-------------------------------

C&VG took particular pride in its

front covers, and they encompassed a dizzying range of styles in the

mag’s first few years. (While illustrations would continue to be

used inside the mag right through the 1980s, the cover would be

increasingly given over to PR shots of commercial releases from

around the middle of 1984. Until that point, the cover would often

be devoted to one of the magazine’s own type-in games rather than a

retail title.) While a core team of artists – each with their own

distinctive style - provided most of the artwork, occasionally the

net would be cast rather wider to produce something even more

esoteric.

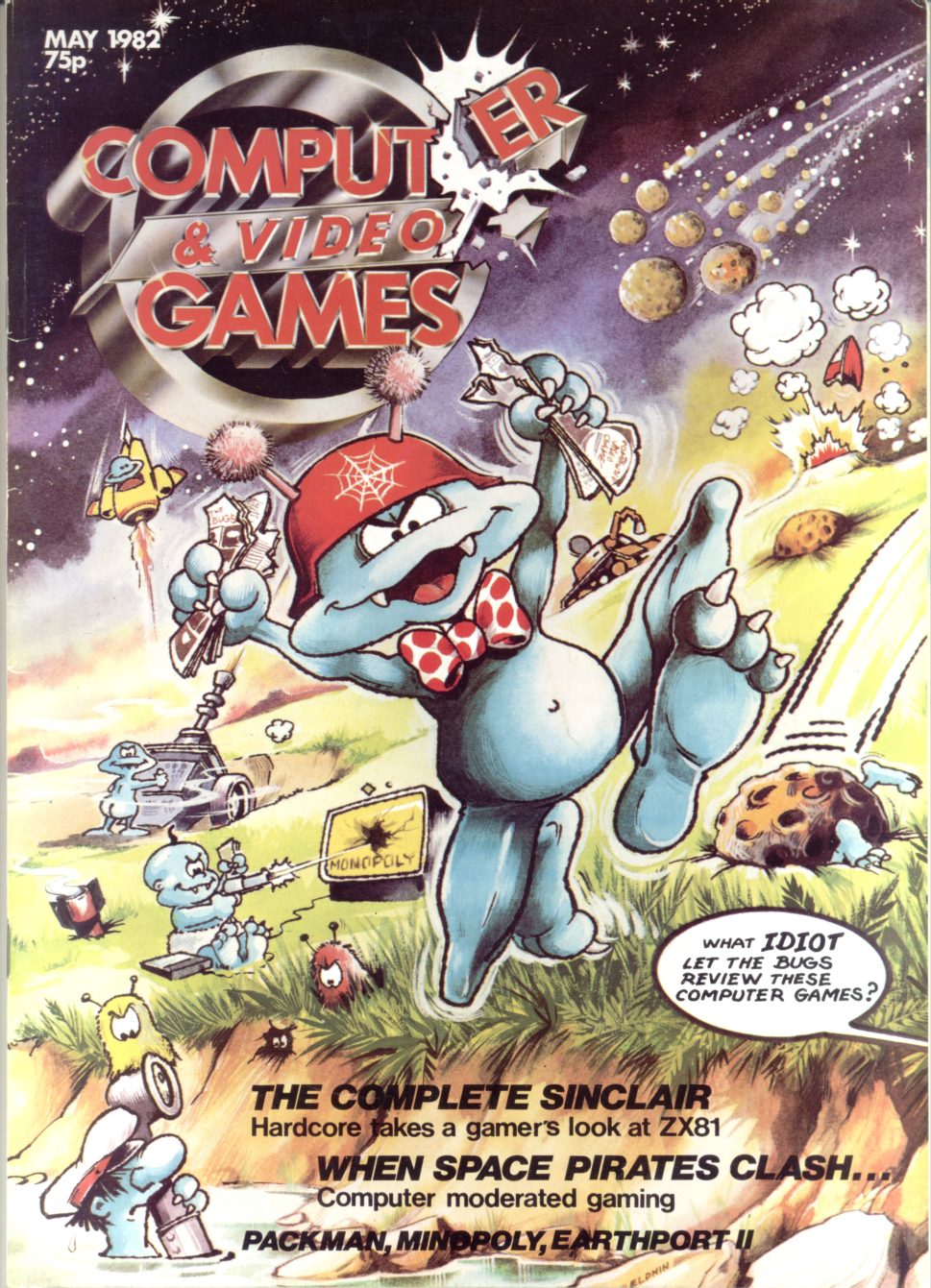

“The Bugs”, drawn by Elphin

Lloyd-Jones, were C&VG’s mascot characters, and featured in their

own full-page comic strip inside the magazine, as well as cropping

up in all manner of random corners elsewhere. This cover from Issue

7 in May 1982 shows them depicted in their full-colour glory for the first time.

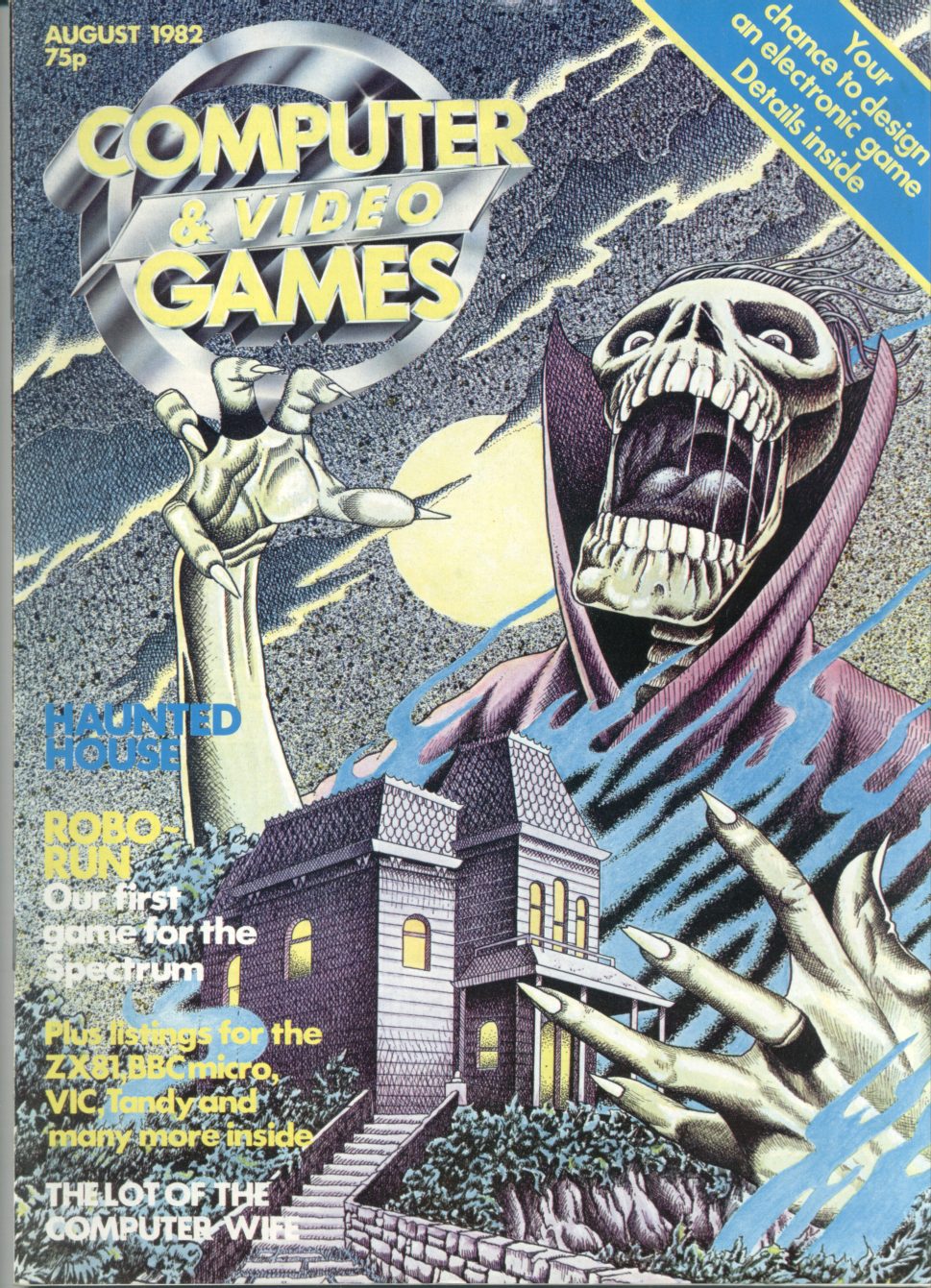

The next image, by Stuart Briers for the

August 1982 issue, combines the spooky horror skeleton with an

obvious homage to the famous Alfred Hitchcock thriller “Psycho”, in

the shape of the trademark house on the hill. If you look really

closely, you can just make out the malevolent shape of Mrs Bates in

the window. (NB Mrs Bates may not be visible in this reduced

reproduction.)

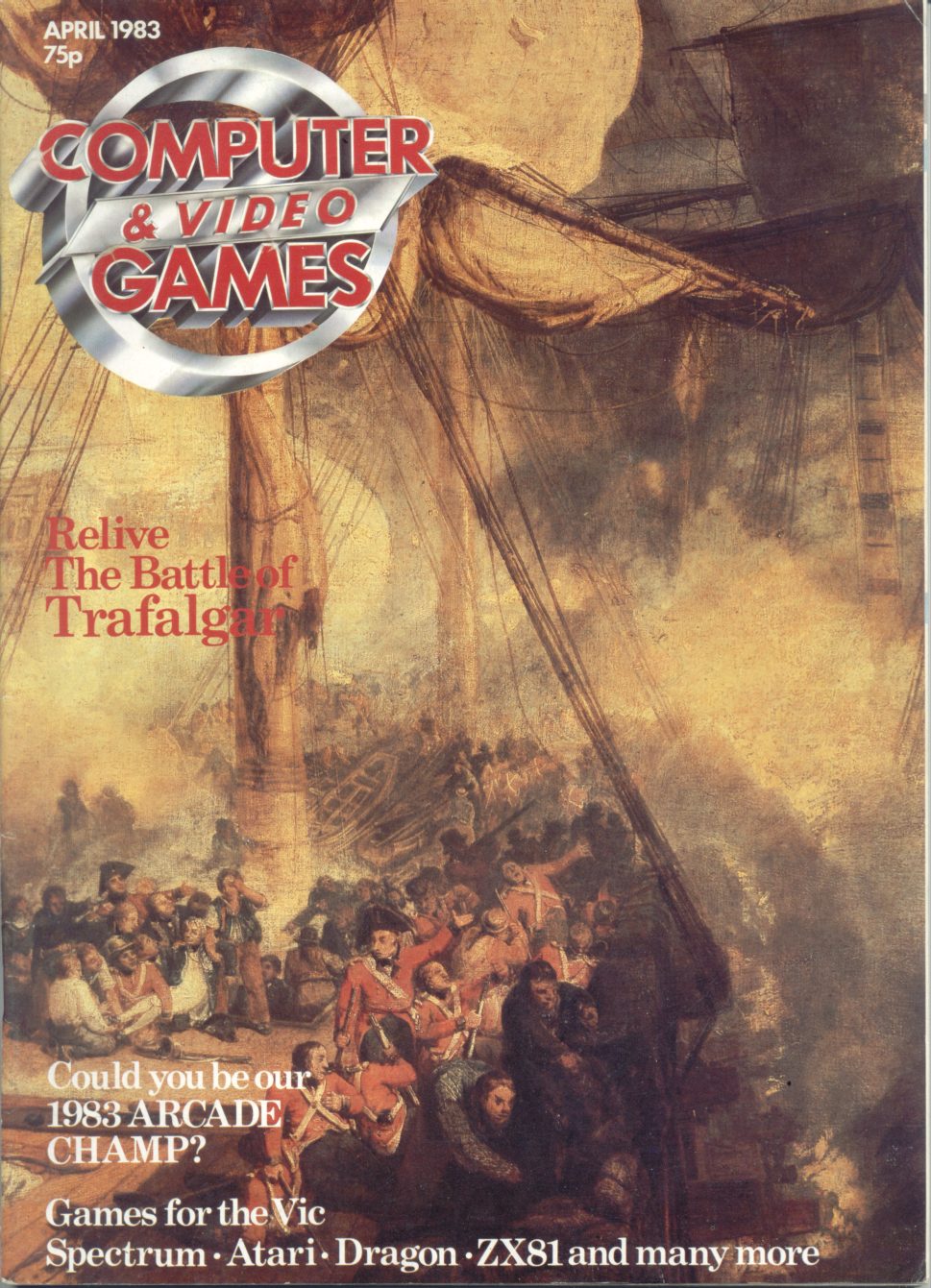

Recently seen in tiny thumbnail form

in another RG feature, this stunning April 1983 cover wasn’t daubed

by one of C&VG’s own brushsmiths. In fact, it was painted around 175

years before the magazine even existed – it’s a detail of “The

Battle of Trafalgar, as Seen from the Mizen Starboard Shrouds of the

Victory”, painted by the English Romantic artist J M W Turner to

commemorate the famous naval victory. The original can currently be

seen in the Tate Museum. Luckily, by the time C&VG came to pinch it,

the copyright had expired…

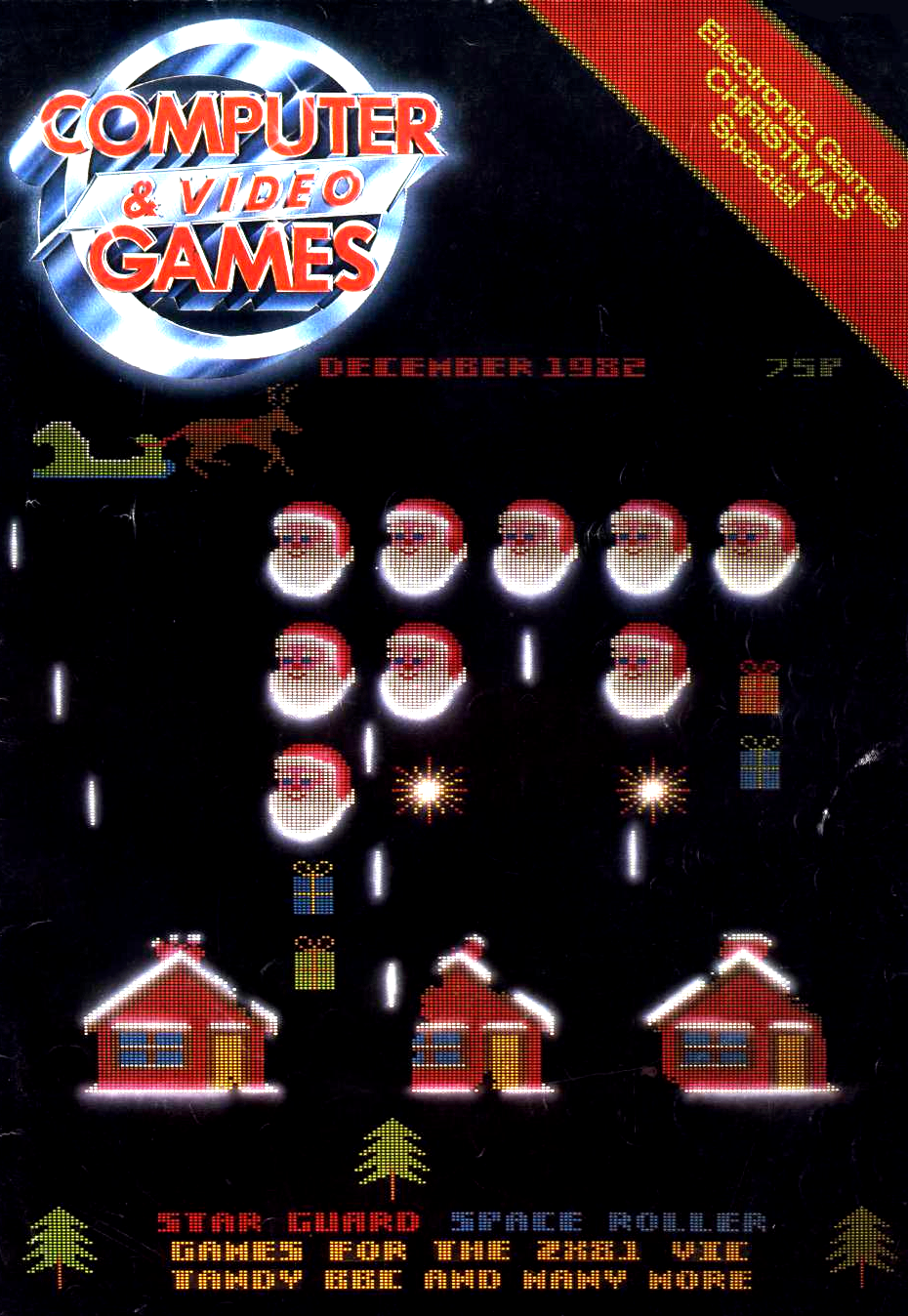

John Thompson created this classic

Space Invaders theme for the 1982 Christmas edition, which

highlights one of the saddest losses of the modern era of mag

publishing compared to old-style reproduction. When games are

photographed rather than screen-dumped, you capture the scanlines of

a TV screen, producing the distinctive “pixelisation” that gives the

image an evocative glow. It looks so nice that most emulators for

the PC (which displays via scanline-free monitors), actually offer

an option to simulate the scanlines to make the games look more

authentic.

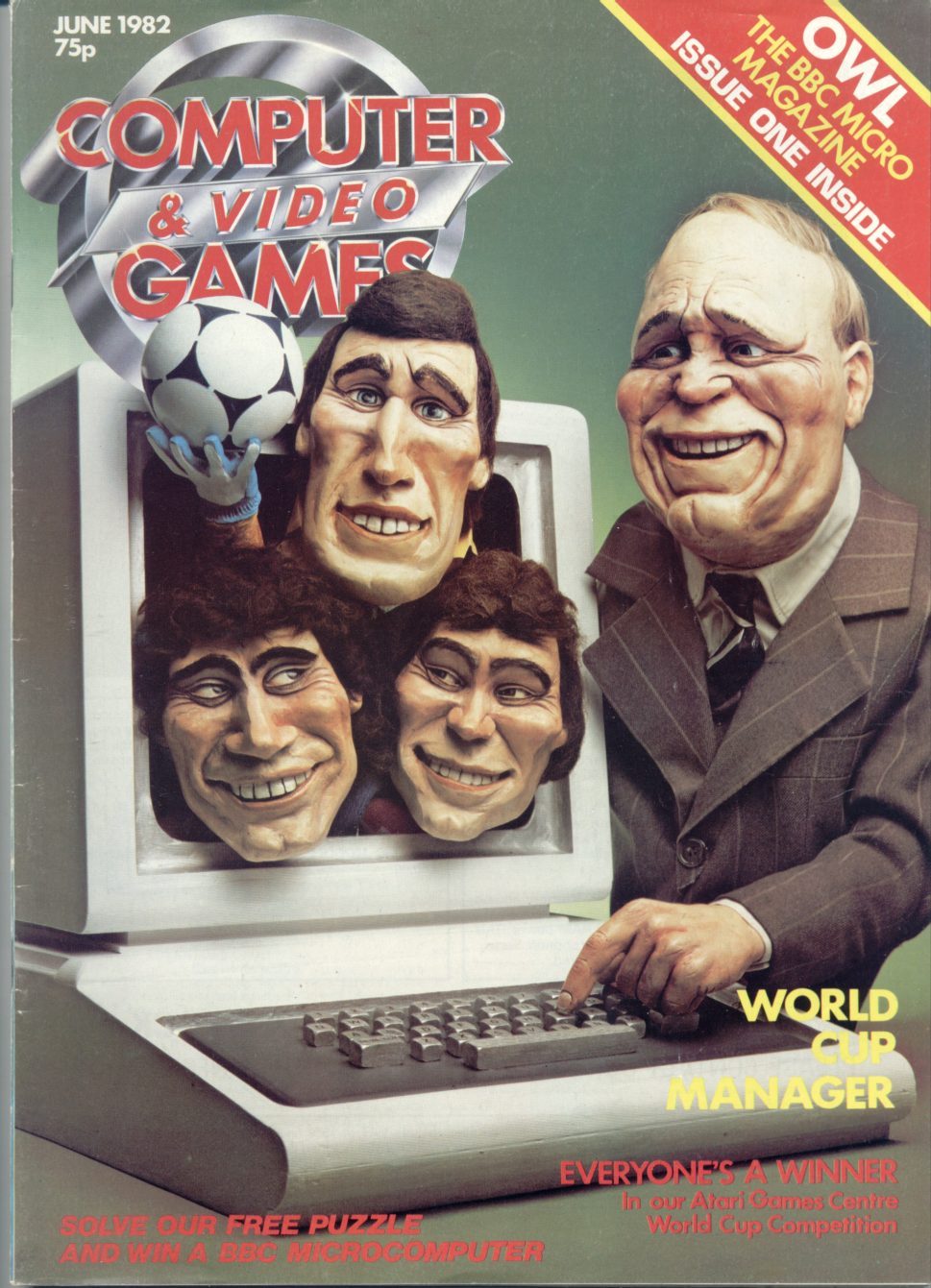

One of C&VG’s stalwart artists was

Dorian Cross, whose caricature art usually enlivened several pages

of every issue. For issue 8, just in time for the start of the 1982

World Cup in Spain, he came up with this spectacular 3D sculpture in

latex rubber, which predated the eerily similar puppets of Spitting

Image by two years.

Apparently, this inventive cover by

Linda Freeman made a serious dent in the sales of the October 1982

issue it adorned, as slow-witted readers confused the mag for an

actual newspaper and failed to buy it. It’s often credited in the

publishing business as the reason people don’t do newspaper-spoof

covers any more.

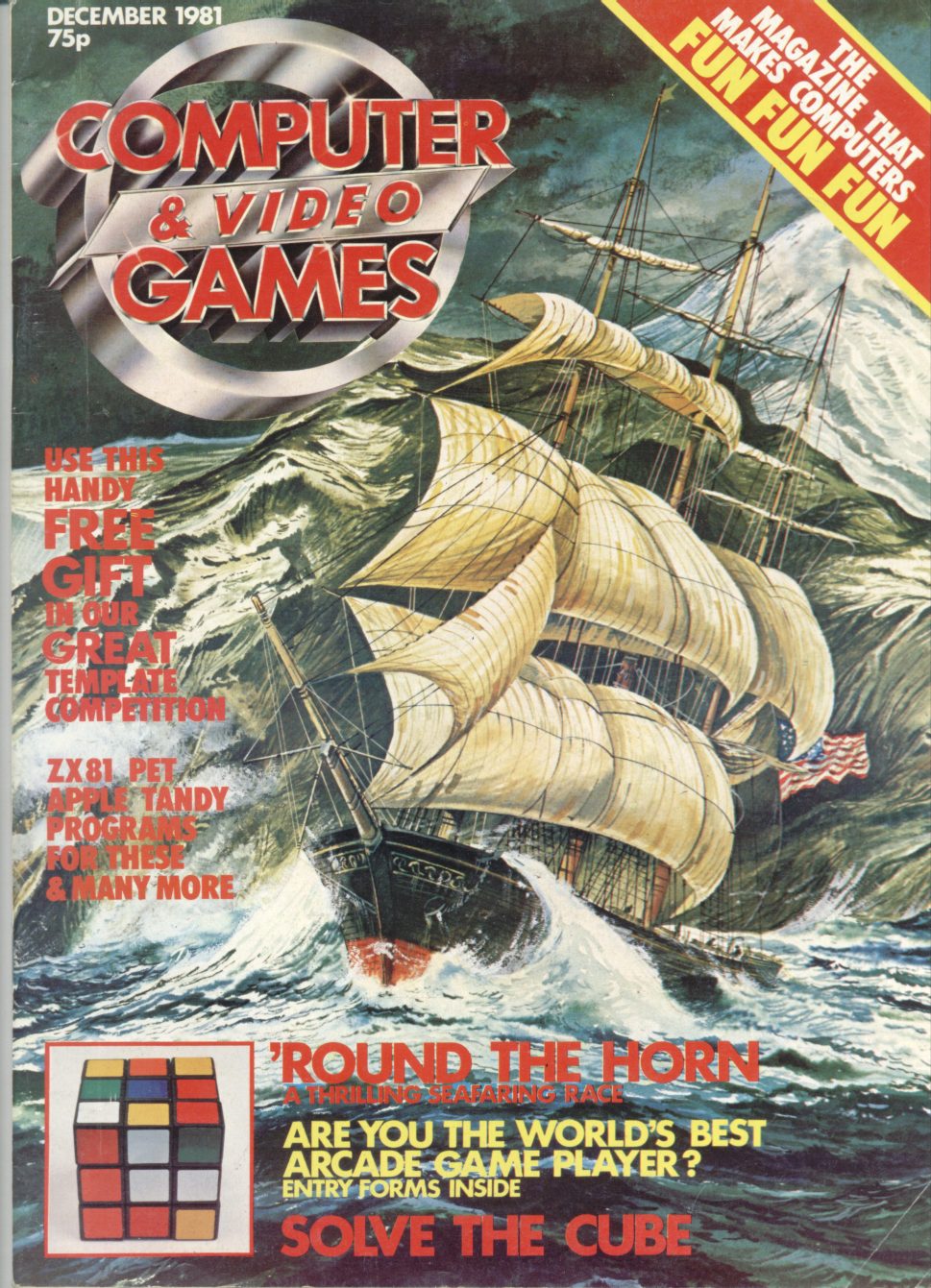

Returning to the nautical theme, the

Tony Gibbons cover for Issue 2 also showcases a trait shared only by

a very few covers, but which demonstrates the incredible commitment

to illustration that early C&VG had. Not only would they commission

someone to produce a full-colour original painting for the cover,

but they’d also get someone else to draw a reproduction of it to

use on the ‘Next Month’ page. Now THAT’S dedication.

------------------------------------------------------

THE POWER OF SUGGESTION

(Part 2)

------------------------------------------------------

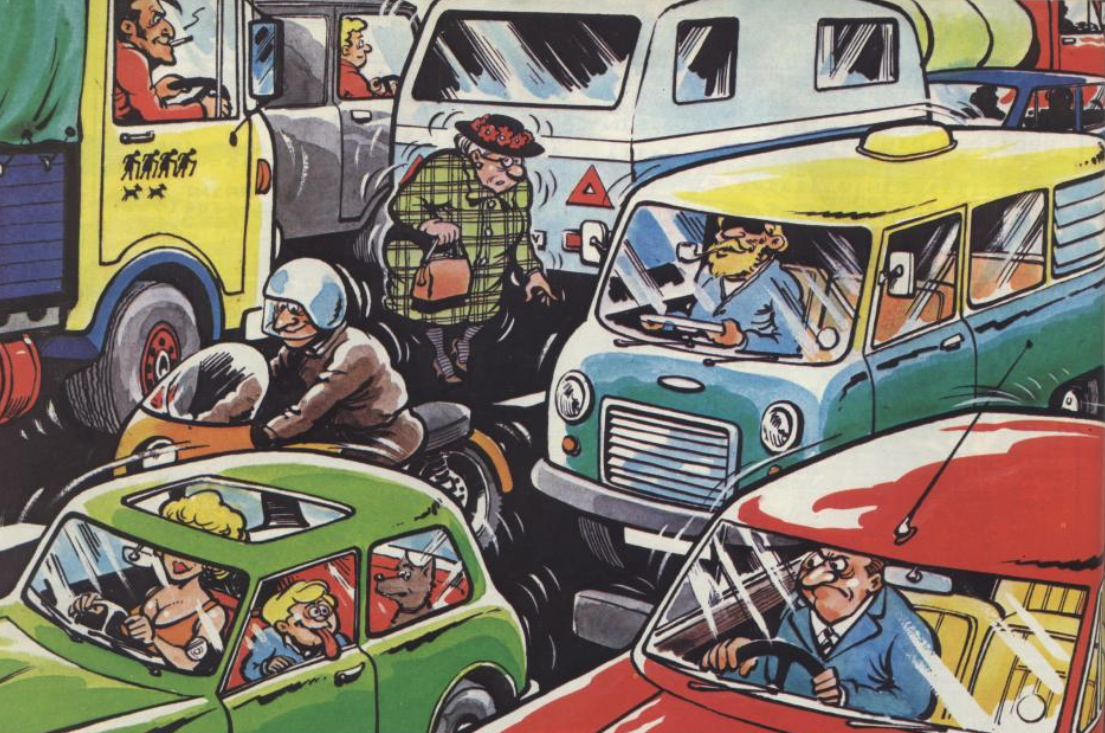

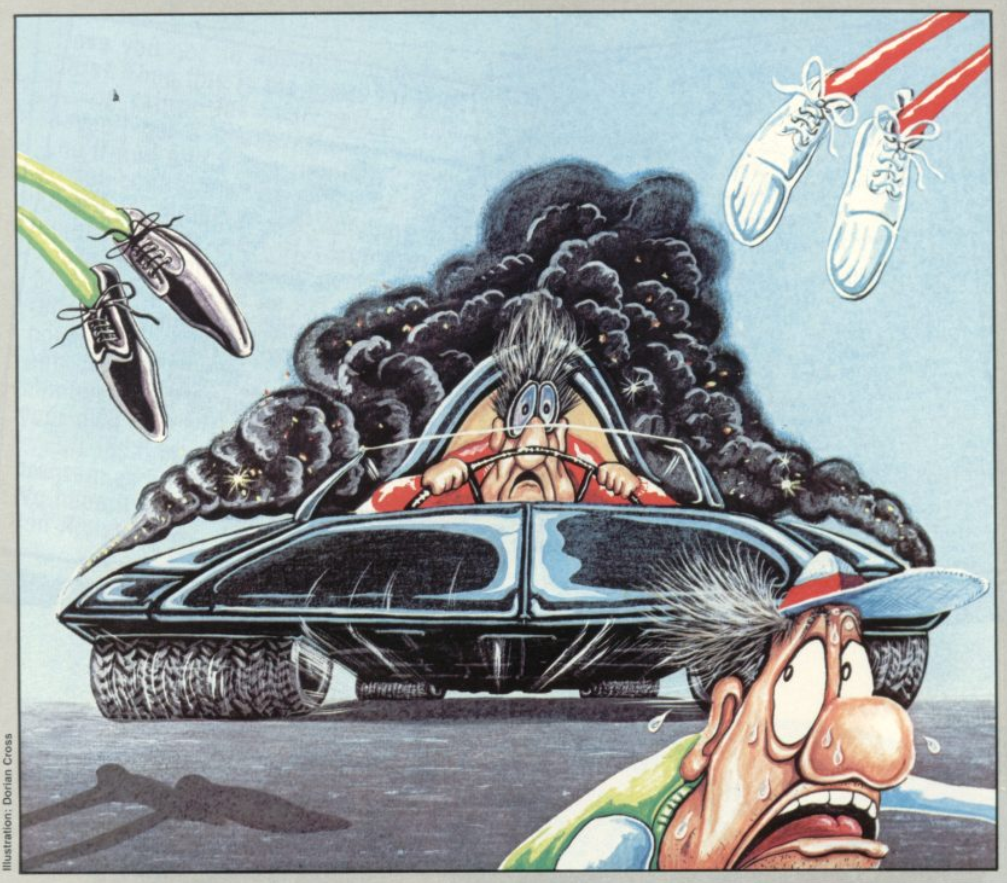

My personal favourite of C&VG’s roster

of artists is Dorian Cross. His bulbous, cartoony figures carry a

very British air of the downtrodden misfortunate, in the tradition

of Tony Hancock, Fawlty Towers, Steptoe And Son or (for our younger

readers) Mr Bean. The following three images show how he could manage to load atmosphere and

pathos even into three of the most basic staple games of the

magazine-type-in genre. The ostensibly racing-themed ZX81 game

Dodgems is

in fact nothing more than a variant of those electronic toys where

you have to guide a metal hoop along a wire without touching it:

But illustrated by Cross it’s suddenly

imbued with a dramatic backstory, where the hapless driver finds

himself at the wheel of an out-of-control racecar (not entirely

dissimilar in design to the ZX81) which appears to

have left the track and is mowing down terrified spectators. This,

you realise, is the human tragedy that awaits if you can’t keep your

car on the course.

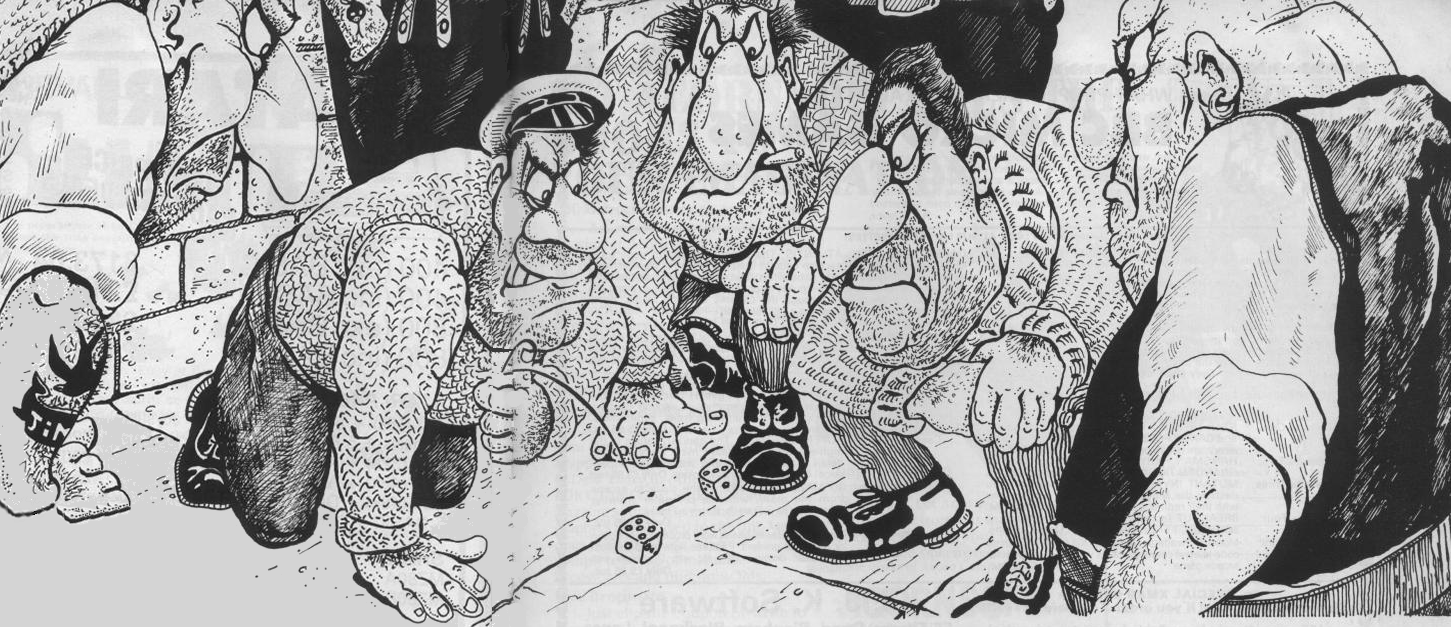

How on Earth do you make a Yahtzee

game seem interesting when there’s nothing more exciting in it than

a handful of dice? Well, you could portray it as being played by a

scurvy gang of scowling merchant seaman on a dockside. Lose this

game and shudder at the all-too-easily-imagined thought of what

might befall you if you can’t pay up on your wager.

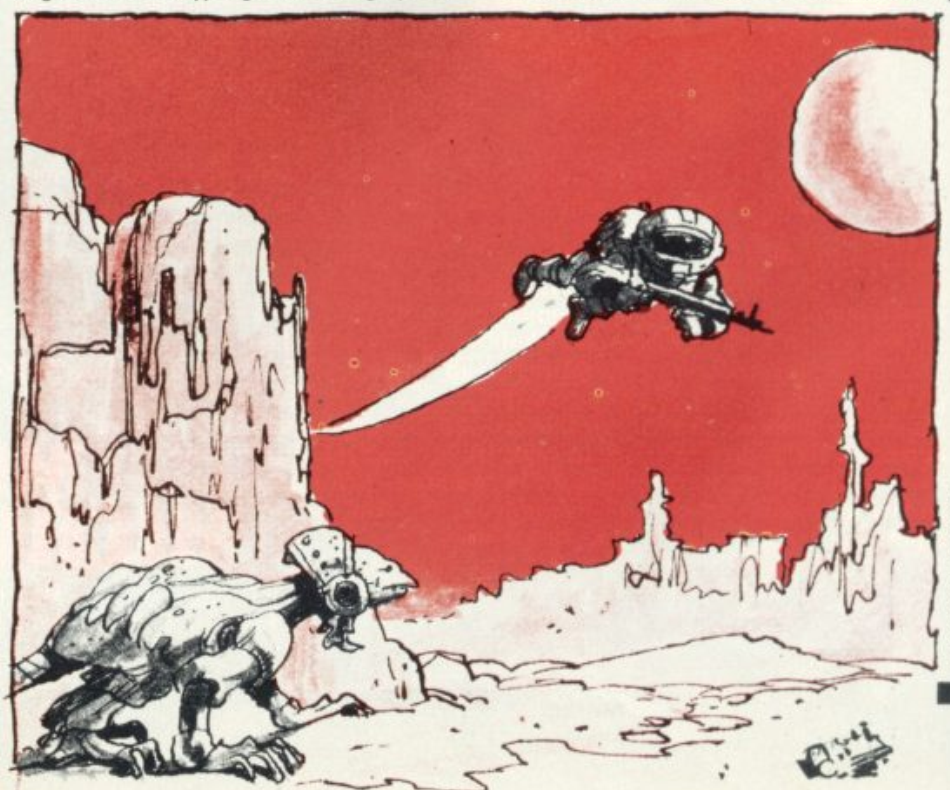

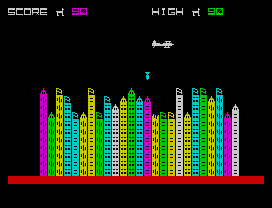

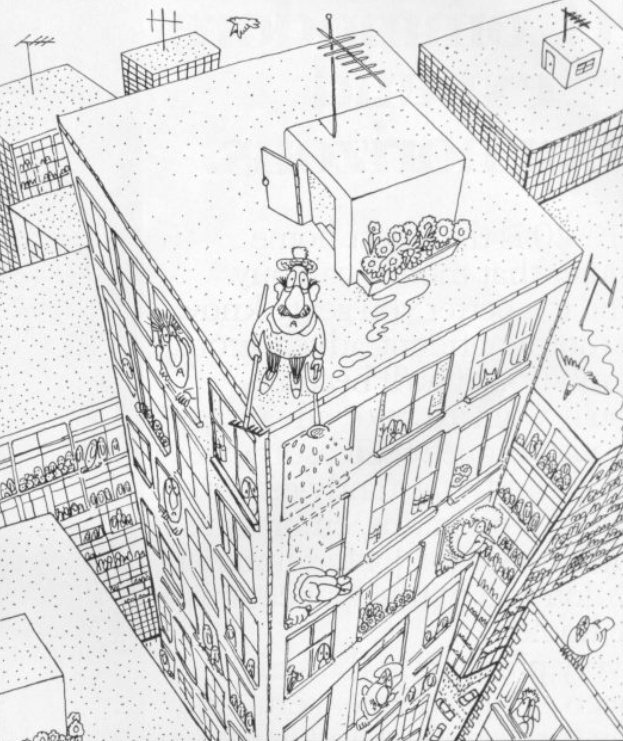

This is my absolute favourite, though.

The “City Bomber” game was an ever-present fixture throughout the

entire era of the type-in listing (though it was also released

commercially - we’ve pictured Jeff Minter’s version). In it, you

pilot a bomber aircraft which is inexorably spiralling out of the

sky, and can only survive by literally bombing flat the city beneath

it to provide a landing strip.

Given this timeworn concept to

illustrate, Cross hit upon with the genius of representing it from

the previously-unconsidered viewpoint of the unfortunate inhabitants

of the skyscrapers below, gazing up in bemused horror at the

catastrophe about to befall them. The detail of the puddle of water

trailing from the tiny window-box to the edge of the building is

heartbreaking, and not until the release of The Getaway on the PS2

twenty-odd years later would gamers be forced to confront the

dubious morality of their actions in such a way.

----------------------------------------------

I'LL NAME THAT GAME IN ONE

----------------------------------------------

ROUND 1

C&VG was the only magazine in the UK

that gave any kind of coverage to arcade gaming, in the form of its

monthly two-page column Arcade Action. Arcade owners didn’t tend to

want photographers getting in the way of their coinslots for hours

at a time, so Arcade Action was almost solely illustrated by custom

artwork. Can you identify these classic coin-op games from the C&VG

artists’ impressions of them? And just to make it harder, we’ve

thrown in a ringer – one of the images is of a home micro game, not

an arcade one. (Answers at the bottom of the page.)

ROUND 2

When a game was popular and therefore

mentioned in several issues of the magazine, C&VG would often hand

the job of illustrating it to different artists each time. Which

well-known space blaster is the subject of these very different

interpretations?

-------------------------------------

WHERE ARE THEY NOW?

-------------------------------------

The tragedy of this story is that, as

far as your reporter is able to ascertain, almost all of the C&VG

artists of the 1980s have disappeared off the face of the Earth.

Despite a month of intensive searching, in almost every case I

couldn’t track down the slightest trace of them still working in any

kind of illustrative field.

The only one who went on to any kind

of fame or fortune related to the games industry was Bob Wakelin,

who drew for the magazine in the latter parts of the decade and

later became very well-known for his work with Ocean Software, but

none of the creators whose work appears in this feature could be

found working either in games or publishing, with the exception of

Bugs creator Elphin Lloyd-Jones (who is, it has to be admitted, by

far the easiest one to Google), who now paints and exhibits on

canvas in a style not far removed from the English Romantic work of

Turner (see Front And Centre), as well as

illustrating children’s books and working on late-80s TV cartoon

Telebugs. It’s nice to think that at least something of the spirit

of the Bugs survived…

QUIZ ANSWERS

| Scramble |

Moon Cresta |

Dig Dug |

Zaxxon |

| Robotron |

Jet-Pac (ringer) |

Congo |

Tron |

| Time Pilot |

Qix |

Elevator Action |

Amidar |

Round 2: the game is Defender.

|