|

THE DRIVING GAMES BIBLE

The

history of driving games is an unusual one. Whereas most genres follow a

linear evolutionary path, becoming steadily more complex and more

technically impressive with time, driving games are different. Driving

games started in 3D and then went backwards to 2D for several years.

They started off quite technically realistic and demanding, then went

backwards and became more simplistic and easier. Graphics got prettier,

more colourful and more dramatic, then went backwards and became greyer

and duller, and so on. We needed someone intimately familiar with the

idea of going forwards then backwards to chart it all, so obviously we

called Stuart Campbell.

Konami’s 1986 coin-op WEC Le Mans, which isn’t mentioned anywhere in

this feature.

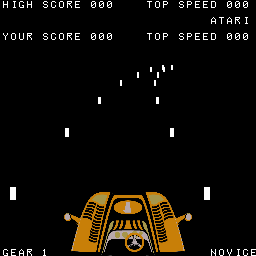

The first instance of driving a car in a

videogame was on Atari's 1976 classic Night Driver. A black screen

faced the player, decorated only with a series of short white posts

disappearing into the horizon to produce an eerily convincing

sensation of 3D. Speeding through the moonlit world at the kind of

game velocity the hardware could impart by, essentially, having no

graphics (even your car’s bonnet was just a plastic sticker attached

to the monitor), you couldn't afford to take your eyes off the

screen for a second.

Steering wheels were next seen in

videogame parlours on the Sprint series of overhead-viewed circuit

games, starting with Sprint 2 in 1976, confusingly followed by

Sprint 4 and Sprint 8 in 1977 and finally Sprint 1 in 1978. The

numbering doesn’t denote sequels - although the various games did

have different tracks - but the number of players. Sprint 8,

impressively, was therefore for eight players simultaneously, all

squished around one fairly normal-sized machine and making arcade

owners swoon with happiness.

To compensate for the lack of human

opposition, Sprint 1 does a remarkable and unique thing: the tracks

change while you’re driving. One minute you’re zooming round

a nice simple loop, then without warning the entire course switches

to a complex crossover route, and then a few seconds later morphs

again to a zig-zag collection of long straights, and so on. If

you’re not expecting it – and why would you be? – it’s hugely

startling and scary.

Night Driver - in fact, not even nearly the first driving

videogame. Fooled you! Ha ha!

Night Driver and Sprint both had purely

demarcative graphics – that is, wholly abstract lines and dots which

served only to mark the distinction between the traversable course

and the “walls” marking the limits of where you could go. The first

coin-op driving game to feature actual graphics in the sense we

understand the term today (that is, depicting some sort of actual

scenery) was Atari’s 1977 release Super Bug, which gave the player

an identifiable vehicle (a VW Beetle) some dense woodland to drive

through. Super Bug also saw the first introduction of “realistic”

handling – in addition to having to cope with manual switching

through four gears (something not seen in arcade games in the

following 30 years), your Bug is prone to drift, fishtailing like

crazy if you go round corners too fast. It’s an incredibly demanding

game which will leave the most dedicated modern racing fan weeping

in a corner within minutes.

Not satisfied with that, though, Atari

followed Super Bug up with the conceptually similar Fire Truck the

next year (which despite still being in greyscale also saw a

significant aesthetic improvement, with the graphics now depicting

an identifiable and rather attractive, albeit somewhat Lego-ey,

suburban landscape with houses, lawns, trees and parked cars).

Fire Truck was the first - so far the

only - co-op driving game, and saw two players charged with steering

a single fire engine through the scrolling overhead course, with one

of them driving the cab and the other trying to keep the trailer

under control. (There was a later single-player version called Smoky

Joe.) It’s absurdly difficult, and almost certainly the most

technical driving game ever created, making a mockery of Gran

Turismo fans and their fiddling with wheel balancing, brake

adjusting and grocket fondling. Only when you can complete a

90-second Fire Truck run without a crash can you consider yourself a

truly skilled pretend driver.

(Atari had also put out another highly

technical and very different coin-op driving game in 1977, the

bizarre side-on precision-gear-shift-timer Drag Race, but that

turned out to be something of a genre dead-end.)

|

TOP FIVE

The

building blocks of the modern racer

New-fangled high-definition Ridge Racer is very pretty

and all that, but

sometimes I miss the old candy-cane primary colours of

the original.

Ridge Racer 2

Probably the first

game that modern gamers would recognise as a racer of

the sort we play today, the original Ridge Racer

slightly predated Daytona USA and is also a far better

game. However, you can’t argue with a sequel that's

basically all the best bits from all the RR

games put together with better graphics, and that’s what

you get in the monstrously-inaccurately-named Ridge

Racer 2.

The only downside - shared with big-brother

titles RR6 and RR7 - is that it starts off terribly easy

where the original was challenging from the off, but

then with only one-and-a-half tracks the original HAD to

be. There’s such a crazy amount of content in RR2 that

it can afford to give a big chunk of it away cheaply at

the start to lure in the beginners and develop their

skills for the stiffer challenges ahead. With the

possible exception of Burnout 2 (see below), simply the

most complete road-racing game of the modern era.

In the early days, Suzuka’s spectator facilities were

sparse.

Pole

Position 2

The first Pole

Position was a phenomenal success, and the sequel

actually did rather less well. However, it was a very

influential pioneer in a very specific field, namely the

inclusion of multiple real-life racetracks. PP1 had

dipped a toe into the water with a pretty authentic take

on the Fuji Speedway course in Japan – the first time a

real-world track had appeared in a videogame - but PP2

offered four selectable courses all based around

real-world race venues, adding recognisable versions of

Indianapolis (a simple oval), Long Beach and Suzuka.

Namco extended the

concept with their Final Lap series, which expanded the

roster with interpretations of Silverstone, Catalunya,

Spa Francorchamps and Monaco, and it’s almost as hard to

imagine an F1 game set in fictitious locations now as it

is to imagine one with only one track.

This is a shot of the rather lovely PS2 remake Virtua

Racing Flat Out, which

is well worth picking up on the excellent-value Sega

Classics Collection.

Virtua Racing

Virtua Racing is a

wonderful game, but it’s historically important for

mostly a strange and unfortunate reason. VR offered four

switchable camera positions, the best of which was the

high overhead cam which gives the driver the clearest

possible view of his racing line. But the most popular

was the first-person perspective, something which had

been rare in driving games until that point, and the

high overhead cam was immediately binned for all Sega’s

subsequent arcade racers, perhaps also because of the

extra processing demands it would make when rendering

their more complex, textured scenery.

The side-effect of

that was to destroy, almost overnight, the credibility

of the entire overhead-view racing genre - which till

then had maintained significant success with games like

Super Sprint, Hot Rod, Super Off-Road and Micro Machines

- and focus future driving-game development entirely on

the first-person view. It’s not much of a legacy for

such a great game, but history can be cruel.

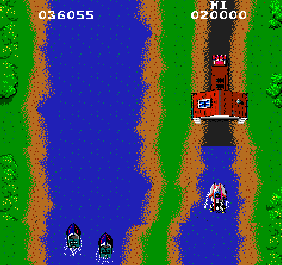

Spy Hunter: also the pioneer in the classic ‘Drive a

motorboat into the

back of a truck parked in a shed and turn it into a

sports coupe’ genre.

Spy

Hunter

Bally’s 1983 classic

Spy Hunter isn’t strictly the first racing game in which

you can directly attack your opponents with weaponry –

you could argue, for example, that Namco’s 1980 Rally-X

claims that accolade with its smoke-screens, or that

Bump’n’Jump from Data East two years later deserves it

by enabling you to actually destroy opponents. But in

the sense we understand the genre today, Spy Hunter is

the crucial first ancestor of games like Mario Kart and

Wipeout, where shooting or otherwise interfering with

your opponents is at least as important as overtaking

them. It was remade in 2001, with modest results.

One of the best games, in any genre, of its generation.

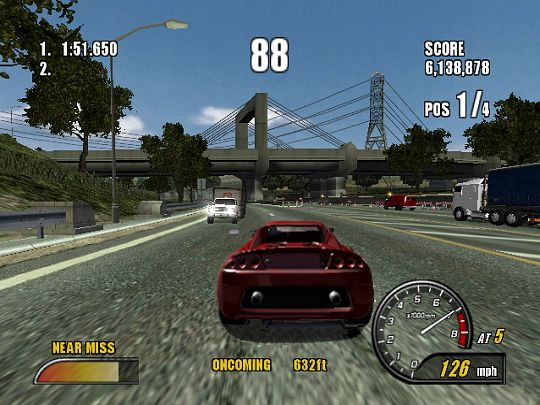

Sadly, it was all downhill from here for Burnout.

Burnout 2

Now derived from the

1984 ram-racing template of Bump’n’Jump, The Burnout

series is an excellent example of why someone invented

the phrase “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”. A

franchise which started with a menacingly serious game

of almost Spartan minimalism and toughness is now little

more than a bloated, devalued insult to the intelligence

of 11-year-olds, offering up spectacular pyrotechnics

and breathless cascades of medals and trophies to anyone

who can hold down a fire button.

But the second game in

the series is a masterpiece, combining white-knuckle

racing tension with the brilliantly cathartic interludes

of the Crash Junctions. Subsequent iterations would

screw up both elements of this simple genius horribly,

but Burnout 2 strikes a perfect balance between

challenge and reward whether you’re racing or crashing.

|

|

TO READ THE REST OF THIS FEATURE

(6,980 words), BECOME A

WoS SUBSCRIBER |

|