|

WHITE WITH NO SUGAR

A journey to the (artificial replacement) heart of England

As the armies of Nazi Germany swept, almost unopposed, across enormous swathes of Soviet territory during the opening weeks of Operation Barbarossa in the summer of 1941, Hitler's commanders reported an unexpected problem that was giving the Wehrmacht more trouble than the few pockets of resistance from the fleeing Red Army. The problem was agoraphobia. So vast, flat and featureless are the great plains of Belorussia and Ukraine (hey, they didn't call them "plains" for nothing) which then made up the Soviet Union's western lands that the soldiers of the Third Reich were being afflicted, said their generals, by "great melancholy" as they covered hundreds of miles without ever seeing anything other than endless fields of grain and the eternally-distant horizon. As the blitzkrieg rolled on and on, the troops were seized by an ever-growing sense of isolation and distance from home, yet without ever getting the compensatory feeling that their goal was getting closer.

It's a bit like that driving through Dorset.

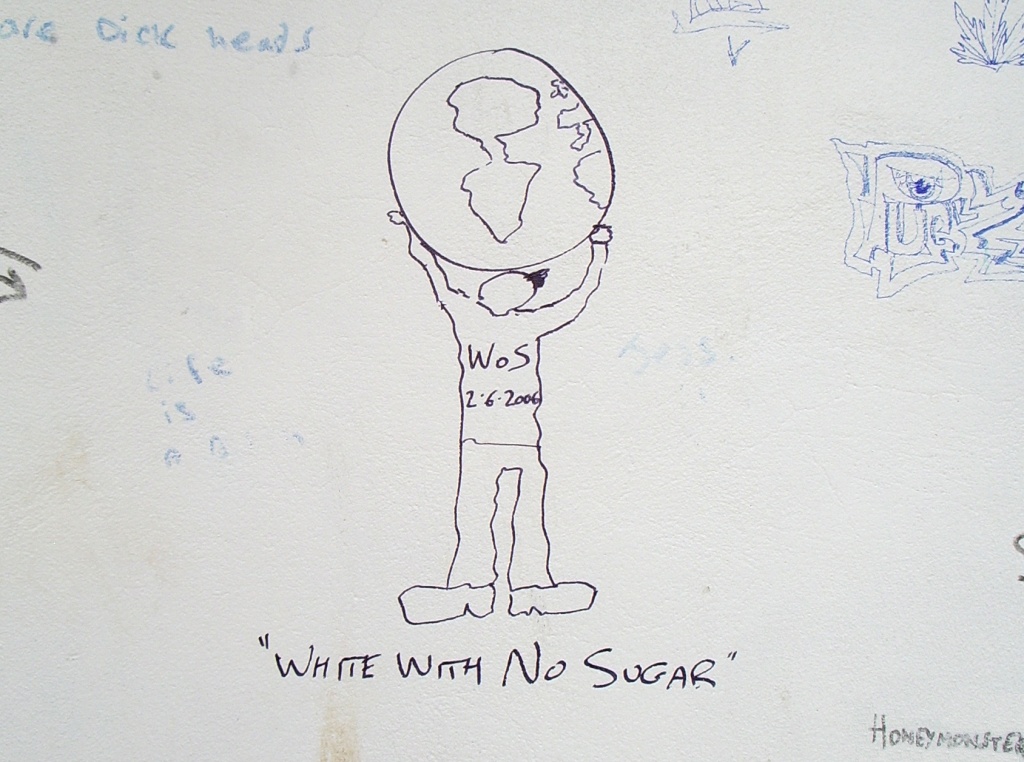

Click the picture to enlarge. As if anything needed enlarging.

Or at least, it is until you unexpectedly encounter a bloke with a huge stiffy carved inexplicably into a mountainside. With the belated arrival of the summer sunshine, your reporter had decided to extract some value from the £550 he'd recently spent getting the WoSmobile through its MOT, by taking a daytrip to not one but two intriguing locations in Nether England. The first port of call was to be Prince Charles' rather sinister "ideal village" of Poundbury, on the outskirts of Dorchester, and your correspondent had already traversed 50 miles of featureless level countryside unbroken by any substantial signs of human life before being unexpectedly jolted into a sudden double-take by the Giant of Cerne Abbas.

The meaning of the carving is still hotly debated by historians (one rather dubious claim is that it's a satirical depiction of Oliver Cromwell, for example) but this reporter's personal belief is that the mere fact of the presence of a smallish hill on the otherwise contour-free surface of Dorset attracted the medieval equivalent of graffiti artists, who - as has been the first instinct of graffiti artists since time began - started off by drawing a big cock and then seeing where inspiration took them.

Perhaps every building is modelled after one of Prince

Charles' houses.

But anyway. It's not hard to notice when you've arrived in Poundbury, which is about 10 minutes further down the road than the happy giant. The building above is pretty much the first one you see, its pristine pastiche of Buckingham Palace somewhat at odds with the rest of Dorchester in much the same way that Robbie Coltrane would be somewhat at odds with the rest of Girls Aloud. Your reporter pulled into the first available road (easily identifiable as part of the "village" by the twee font on the street sign) and immediately found a parking spot, something which was soon to become apparent as a key design feature of the village.

The area occupied by Poundbury is roughly 400 yards square, and walking around it is a bit like watching a DVD of the history of English architecture on fast-forward. Turn any corner and you'll find buildings in a completely different style to the ones on the next street. I'd expected a creepy uniformity, with Neighbourhood Watch patrols checking that nobody had painted their front door an unapproved colour (though apparently there ARE rules about that sort of thing) or exceeded the permitted levels of garden-gnome cheekiness, but in fact it looks as though the place was built by anarchists. Thatched-style (but not actually thatched) cottages sit turret-by-cupola with Georgian terraces, Edwardian villas, traditional Coronation Street red-brick, and urban-modern gable-ends with glass cutaway panels. (And weirdly, almost like some kind of freakshow, a single derelict old ruin right in the middle.)

Even houses in the same terrace are often built in different styles.

If there's one thing that does leap out at you about Poundbury, though, it's whiteness. Or, to be more precise, magnolia-ness. Architectural variations aside, this is one pale-coloured little burg. Perhaps 80% of the buildings are painted in either purest white or the faded yellow tone of clotted cream, and even the pavements aren't the usual dark grey tarmac but a light sandy-coloured gravel which makes every step you take sound like a large and well-drilled military parade. (You can just forget about sneaking up on anyone in Poundbury.)

It probably won't make alert WoS readers fall off their seats in surprise when they hear that this phenomenon extends to the inhabitants of the village too - in the entire three hours your reporter spent wandering around, I didn't spot a single off-white face anywhere. In fairness, though, it ought to be said that there weren't many faces of any colour to be seen. Even though it was half-term, the playgrounds were deserted and your correspondent shared the immaculate streets and open spaces with remarkably few other humans, although their cars (polished, without exception, to a dazzling laser-intensity gleam) were parked everywhere. The simple explanation for this, however, may be that there isn't actually anywhere to go.

If you could sum Poundbury up in just one picture, it'd probably be this one.

The one thing that's really conspicuous by its absence in Poundbury is - ironically - shopping. What few commercial premises are present in the village are solicitors, stockbrokers, temping agencies, clinics, nursing homes, "enterprise centres", art galleries and furniture designers. Places where you can walk in and purchase actual physical goods are practically non-existent, and it took your correspondent two hours to stumble across the "Poundbury Village Stores", which was in fact a single branch of Budgens hidden behind a pretty facade. There are, as far as your reporter was able to ascertain, no cinemas, no theatres, no restaurants, no takeaway food outlets (not even a "Ye Olde English Fish And Chippe Shop"), no petrol stations, no Boots, no Dixons. In fact - and this is the point at which it dawns on you why the place feels so unreal - there's not a single corporate logo or frontage to be seen anywhere. Even the Budgens could only be identified as such from within, by the logos on the staff uniforms, own-brand products and price stickers.

(One of the preconceptions I'd set out with about Poundbury was that it would be a nostalgia trip for a past that never really existed, all brand-new thatched cottages and the ambience of a National Trust theme park. It's not like that at all. It's more like the Daily Express decided to secede from the rest of Britain and create its own modern nation state, where Englishmen would be free to hunt foxes in huge Land Rover 4x4s, and do as they chose without being sullied by the influence of foreigners or a damnedable nannying central government, and where life would be so idyllic and free from conflict that the only need for policemen would be to conduct neverending investigations into the death of Princess Diana.)

There were 30 cars in this car park, but only six people in the shop.

The other sense in which Poundbury feels different to almost anywhere else in Britain is how car-friendly it is. In fact, we're not talking "friendly" so much as "subservient". This is somewhere built from the start on the premise that every family will own at least two cars, and so will everyone who might ever come to visit. Accordingly, there isn't a parking meter or a double yellow line to be found anywhere in the village. You can pretty much just stop wherever you feel like it, get out and leave your car there indefinitely. In addition to generously-proportioned free public car parks, there are plentiful garages, comically ornate drives, expansive back yards, and plenty of room in front of every house for residents' own vehicles. (Nowhere here will you find that omnipresent curse of even modern urban housing development, whereby a brand-new purpose-built block of 20 "executive" flats will have exactly 20 parking spaces, plus a grudging two for "guests" that you have to book six months in advance if anyone should ever want to come and see you.)

Almost uniquely, as an outsider arriving for a visit you feel immediately welcomed like a prodigal son, purely by dint of the fact that you're not being implicitly urged to leave again at once by being charged two weeks' wages just to get out of your car for 20 minutes. If there's one way in which Poundbury IS unarguably superior to the rest of Britain, it's that.

The only parking restriction your reporter could find in the whole of Poundbury.

But the side effect of the characteristics outlined in the last few paragraphs is that cars actually appear to outnumber people in the village, by several to one. Apart from a single rather dark pub, your reporter hadn't yet encountered anything that could pass as a communal gathering place where people could come to - for want of a better phrase - express themselves socially. Poundbury was clean and pretty and light, full of grassy public spaces and greenery and fountains and charming piazzas, but where was its soul?

At the last minute, the answer turned up via the unlikeliest of places - an estate agents.

The fountain in front of Wyndhams deli is one of the more Prisoner-esque features.

On finding the "Poundbury Village Stores", your reporter was pretty sure he'd explored the limits of the village. Poundbury is expanding remorselessly outwards, and the two sides of the village that don't border on Dorchester are massive building sites, increasing the numbers of homes and offices at an exponential rate, and the Budgens appeared to occupy the last inhabited area I hadn't already covered. But ever since arriving I'd been curious to find out how much it cost to live in this strange little fantasy world, and it seemed bizarre that throughout my intrepid explorations there hadn't yet appeared to be an estate agents.

And sure enough, just across the road from the store, I finally spied one. A quick look in the windows provided the unexpected information that both rents and purchase prices in Poundbury were, if anything, slightly below the corresponding rates in Bath, but it was glancing down to the end of the street that brought the real surprise.

Perhaps it's for taking a break during the long 10-yard trek from car park to pitch.

Visible about 100 yards away at the end of the road, right on the edge of town between yet another car park and a somewhat overgrown rugby pitch, was an inexplicable little Roman pavilion, standing all on its own. It was about the size of a bus shelter, but plainly wasn't one, and it appeared to serve no immediately-discernible purpose, other than to provide people with a seat with a view of the car park. Perhaps the builders just had some columns left over when they'd finished someone's gazebo or something.

Bemused and intrigued, I headed up to take a closer look at this seemingly-gratuitous structure, but on initial inspection the apparently featureless construction provided no enlightenment as to its intended function. Until I went round the back, that is.

Having a handy stile there seems to rather defeat the object of the barbed-wire fence.

The shock of the rear of the Inexplicable Pavilion was akin to the sensation of having a bucket of cold water thrown on your face when you're sitting slumped against a wall on the floor of your friend Louis' house in a drunken stupor after spending an extended lunchtime drinking pints of cider-and-Pernod (er, for example). Where every other white surface in Poundbury was immaculate and virginal, the pavilion's back wall (which, perhaps crucially, isn't overlooked by any houses) was an explosion of surreal, disturbing and anatomically- questionable middle-class graffiti. Including, in what's a suspiciously neat tie-in with the beginning of this feature and which doubtless goes to prove something tremendously deep and significant about human nature although WoS doesn't know what, a big cock.

Whether the rebellious teens of Poundbury have simply found the one place where they can record their profoundest thoughts unseen by disapproving eyes, or whether the pavilion was built for this express purpose and gets re-whitewashed anew every month, or whether the entire thing is actually a Turner Prize-winning abstract art installation created by Tracy Emin and Damien Hirst, this reporter can't say. What can be said is that your limited-but- enthusiastic correspondent hotfooted it back to Budgens, bought a 99p magic marker, and left his own disfiguring marks in Charles' slightly-too-perfect world. (There'll be WoS bonus points aplenty for anyone who goes to Poundbury and finds the second one, which takes the form of a short poem entitled "What Shall We Do With The Prince Of Wales?")

With that, it was time to head back to the car and press on towards the second leg of your reporter's epic three-part journey. And if any particularly alert viewers are scratching their heads at this point and going "Hang on, I thought you said you were going to TWO intriguing locations, not three?", well, just you wait and see.

|