|

SONGS TO LEARN AND SING

Magnapop - "13"

I'm pretty old. I also have a lot of spare time, and those two facts mean I think about stuff a lot. Far too much, in fact, because in my experience the more you understand about the world the less happy you are - Christ knows how Stephen Hawking even gets up in the morning. (Oh, right. Sorry.) But eventually, inexorably, you come to a plateau of experience where nothing much surprises you any more, and every new horror doesn't shock, just wearily reaffirms what you already knew about the ugliness of the human condition.

People voluntarily voting away centuries of civil liberties for Nazi-style scaremongering? Governments openly advocating torture of prisoners who've never been charged with a crime? Thousands murdered in factional wars over schisms in ideology so trivial and abstract you can barely even comprehend them, far less grasp why anyone would be driven to slaughter generations of innocents for them? It's all just more of the same, and past a certain age it barely raises an eyebrow, never mind setting your soul on fire with righteous fury. You know how things are, so why keep getting yourself worked up pointlessly?

I first heard this song about 15 years ago. I still don't know what I think about it.

Originally recorded by the slightly creepy 1970s godfathers of emo Big Star, the version that actually introduced me to "13" was a cover by US noiseniks Magnapop on their eponymous debut album, and it's still my favourite take on the song. But we're a little ahead of ourselves here. At the most generous interpretation, "13" is a paean to (very) underage sex. At worst it's a hymn in praise of paedophilia. The identity of the singer - whether it's a classroom sweetheart or sinister predator - is never explicitly made plain. What evidence there is leans slightly towards the former, but either way we're talking about statutory rape at best. And if the title's inconclusive, the opening line coldly removes the comfort of doubt: "Won't you let me walk you home from school?"

The traditional portrayal of the paedophile, of course, is of an older man preying on young girls. So in having the cover sung by a woman there's a twist straight away. Is this an attempt to somehow neutralise the song's evil (like U2 introducing "Helter Skelter" with the words "This is a song Charles Manson stole from the Beatles. We're stealing it back") by taking control of it, and therefore its power, away from the abuser? Or is it turning the situation round to present the hypocrisy with which society views the phenomenon of underage sex if you reverse the usual genders? (If a young girl is molested by an older man, everyone wants him killed. If an older woman has sex with an underage boy, most people - most men, at least - think of the victim as a "lucky bastard".) Or is it neither of those things, and simply the same story of young love told by the other participant?

While the original, and most other versions, play it as a rather folkish acoustic ballad, Magnapop muddy the picture further by producing something altogether more intense. Starting with a prowling, menacing bassline and sparse reverb-heavy drums, the revelatory second half of each verse is consumed in fiery guitar noise. Where each set of opening lines are delivered with an innocent sweetness, the ensuing parts carry a lascivious yearning that borders on threat. In the first verse the words "…and I'll take you" ostensibly refer harmlessly to a school dance, but Magnapop's Linda Hopper enunciates them with an almost-sneer that implies something a lot less innocuous. In the original, the second verse's reference to "Paint It Black" suggests an everyday musical discussion about the Rolling Stones' work - in Hopper's hands, as the incendiary guitars start to lick around the line's feet, it's a full-blown invocation of Their Satanic Majesties, and the words "Come inside where it's okay / I won't shake you" sound like an empty promise.

(Curiously, this is a lyrical change in the cover - the original pledges that the narrator WILL shake the object of his desire, yet sounds far less ominous than Hopper's vow of inaction.)

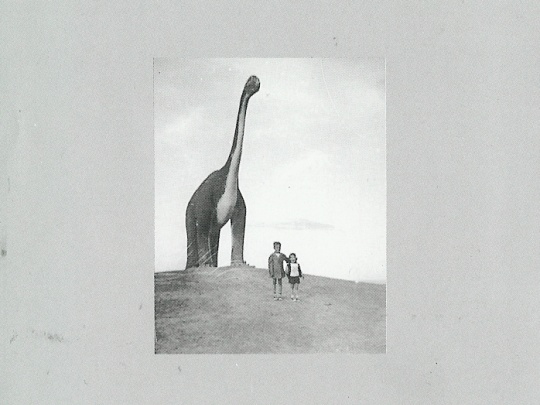

The highly-apt front of the "Magnapop" album sleeve.

The third and final verse, though, is where the song really shows both of its faces. The first two lines are spine-tingling: "Won't you tell me what you're thinking of? / Would you be an outlaw for my love?" There's no ambiguity any more - this desire is unequivocally breaking sacred rules, and the singer is openly inviting their object to come with them to damnation. But as the guitars whip up a final squalling crescendo, a note of nervousness and fear slips from behind our protagonist's mask of seductive confidence: "If it's so then let me know / If it's no, then I can go / I won't make you."

The dread of the negative response is palpable in Hopper's quivering voice, and all too familiar. We’ve all put our hearts on the line at one time or another. We've all asked the same question, and we've all waited in that eternity for the answer. We've all experienced that very same plight, exposed and vulnerable and desperately hoping amid a maelstrom of noise. But. What they want is wrong. After all, they've just confessed their desire for a child. Empathy and revulsion fight a life-or-death battle for our souls - can love be codified and imprisoned in a set of rigid human rules and numbers? Is everything really black and white? Can we judge the story on the information at hand? Do we even have a right to try?

Don't ask me. I don't know.

In "13" the answer never comes, of course. And that's why everyone should hear this song. As we get older, our views tend to ossify. We're less prepared to endure (or admit to) uncertainty, to have our perceptions challenged or our prejudices confronted. But 15 years on, every time I hear "13" I still don't know whether it's a beautiful declaration of purest, innocent love, a sick and perverted horror story, or both. And - in a scenario that carries an inescapably disturbing parallel with the subject matter - that's why I love it.

I love it because it makes me uncomfortable. I love it because it makes me unsure about what I believe. I love it, in other words, because it makes me feel young.

|