|

STOLEN FROM THE PEOPLE

I ain't afraid of no ghosts.

It's not easy to find the "ghost village" of Imber. On maps its location is a great big blank space, and it doesn't appear on any road signs. You only know you're in the right area when you spot a single "Tank Crossing" sign about a mile south of West Lavington, and glance across to the unassuming little single-track road bearing the notice of whether the roads through the village are open or not. "Not" is nearly always the answer - Imber's only open to public access on a handful of days every year - but we're getting ahead of ourselves.

A helpful guide to anyone trying to locate Imber, courtesy of Microsoft Autoroute.

In the winter of 1943, the War Office informed the inhabitants of the small Wiltshire village of Imber that their home was being requisitioned for the war effort. With the D-Day landings just a few months away, the government needed places to train American troops for the sort of house-to-house fighting that they expected to encounter in Nazi-occupied Europe, and presumably because of its location in the middle of Salisbury Plain, Imber was an ideal candidate. The villagers were given a month to evacuate, and told they'd be allowed back when the war was over. They never were.

The nearest thing in existence to an Imber roadsign. (Click all these pics for larger versions.)

From 1943 to the present day, Imber has remained an Army training ground, where Britain's soldiers practice fighting enemies in and around civilian areas. It's highly likely that it was used to train troops for the invasion of Iraq. But for most of August, and on a few other public holidays during the rest of the year, the roads through the village are open and anyone can wander around it. On one day every year (usually the first Saturday in September), the 200-year-old village church, St Giles, is allowed to open for a service and to allow the few surviving villagers and their descendants to visit the graveyard where their relatives are buried. More detailed background on the history of the village can be found in a book, but this feature describes your correspondent's own personal odyssey of 17 August 2005.

The guard post, located 100 yards or so from the main road.

On a beautiful, sunny summer's day, the drive from Bath to Imber is a scenic and leisurely one (especially if one's fortunate enough to own an open-topped car), notwithstanding a harrowing accidental diversion through Devizes on account of missing one of the journey's many turns down narrow, barely-charted B-roads. On finally locating the road into Imber, your correspondent's sense of excitement was palpable, and spirits were high as amusing roadside signs warning of "Tanks, mud and potholes" marked the way.

See? Told you so.

A few dozen yards on, and less chucklesome, are the first of countless admonishments not to leave the carriageway for fear of "UNEXPLODED MILITARY DEBRIS", which swiftly impress a more suitable state of mind on the daytripping tourist. This is a serious place. Just how serious becomes even clearer as, idly scanning the vast rolling plains (Imber itself is still a couple of miles away), your eyes suddenly pick out some of the wrecked tanks littering the idyllic countryside, their rusting brown hulks blending in with the low scrub. They seem to multiply the closer you get to the village, and get closer and closer to the road, with an increasing sense of menace.

How many tanks can you spot in this picture? Write in!

Still, a mile or so along the lonely track across the top of the plains, you catch your first glimpse of the belltower of St Giles' church through the trees, and you can feel an ancestral memory of what a peaceful place this must once have been, almost unchanged by the passing of ages. Focus your eyes straight ahead, free of the tank hulks and warning signs, and you could pretty much believe yourself returned to the Middle Ages. No electricity pylons, no overhead cables, no aeroplanes, no petrol-station canopies, no traffic noise. The only thing you'll notice, in fact, is how bloody loud crickets are in their natural habitat..

We're about halfway to the village here.

At this point, captivated by adventure and anticipation, your reporter gunned the engine and raced at exciting speed towards Imber, with the car stereo blasting out ("Low" by the Foo Fighters, trivia fans), getting that rare rock'n'roll-cliché feeling of what it must be like to journey across the vast empty expanses of America with only the endless sky for company. With none of England's ubiquitous hedgerows to obscure any traffic or hazards ahead, and nobody in sight to disturb with the noise for at least a mile in any direction, your correspondent was in a Heaven of hedonistic solitude, and sped on towards the goal.

So don't, for example, stand on the grass verge to take a picture of the sign.

Arriving in Imber itself, your reporter had not one but two of his short-lived illusions abruptly smashed. Firstly, a notice warned that even at this favoured time of year, only the main road through the village is actually accessible to the public, not the village itself. And secondly, far from being silent and deserted, as your correspondent had imagined it to be late on a Wednesday morning in the middle of August, the village was in fact considerably populated.

An armed man, yesterday. (At time of writing.)

Both of these facts were brought starkly home when WoS' intrepid adventurer got out of the car and wandered off, camera in hand, along one of the village's minor roads (having misinterpreted the signs to mean that you were allowed to go on the roads, but not into or around the buildings), in search of a particular house, previously spotted in a short web article on the village. A very polite young soldier attracted your correspondent's attention, and explained that even during times of public access the village is still used for Army training, and all but the main road are out of bounds, on account of the presence of weapons and live ammunition and the chance of getting one's head blown off should one pop it unexpectedly around a corner.

Shortly afterwards, smoke started billowing out from behind this building.

(As if by way of illustration, the peace of the village was at that moment shattered by some blood-curdling screams. On arriving, your correspondent had observed what he initially took to be some wooden training dummies standing to the rear of one of the houses. Suddenly, however, these "dummies" had begun some sort of exercise, resulting in the sound of gunshots swiftly followed by (acted, hopefully) screams of pain, and an instructor shouting "You're dead!" at the unlucky victims.)

You can't really make the graffiti out in these thumbnails, but it can be seen in the full images.

Fortunately, it happened that your reporter had already located the thing he really wanted to photograph, which was a piece of graffiti painted on one of the buildings by persons unknown (but presumed to be former inhabitants or their children) a couple of years ago. Many of the buildings in Imber still bear the visible signs of this clandestine assault, despite the efforts of the Army to remove them. (Which is a bit of a mystery, if you think about it - presumably, if you're practicing attacking what might be enemy territory, some hostile graffiti would only add to the authenticity.) Despite the attempts to remove it, you can still see, in the picture above, the phrase that gives this feature its title.

I can't tell what this one used to say. But you can still read the slightly sinister "REDRUM".

It's a combination of these factors that gives Imber its eerie, chilling character. The few remaining original buildings (most, obviously, having been destroyed in all the simulated fighting) mingle with purpose-built brick shells with simple corrugated-iron roofs. You have an acute sense of being somewhere nobody really wants you to be, a long way from anywhere, surrounded by armed squaddies eyeing you suspiciously. And on a more personal note, your correspondent can attest that you feel really conspicuous arriving on this scene in a brightly-coloured open-topped sports car with the Foo Fighters blaring out of it. It's a Slaughtered Lamb kind of experience.

Still more convivial than the Bath pub of the same name.

Indeed, given how little of the original Imber survives, it's surprising how much character remains. You can't get near the church, but the other traditional centre of the English village community, the pub, is conveniently situated right on the main road. You can even poke your camera through a small hole in the wall and use its flash to illuminate the ruins within.

It's slightly odd that our soldiers are apparently training to assault empty buildings.

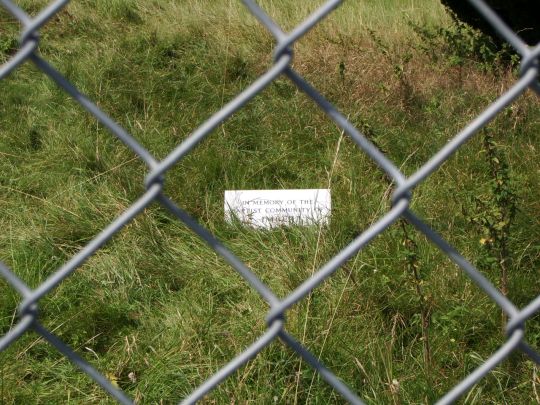

A few feet past the pub, a blue sign announces "BAPTIST CHURCH", with the words "OPEN" appended below it. Following the tape-marked pathway leads you to a fenced-off enclosure marked, contradictorily, "OUT OF BOUNDS". There's actually no church within the enclosure - it became so dilapidated that it had to be demolished years ago - but a small number of gravestones can still be seen. (It's a curious facet of English life that a village of fewer than 150 inhabitants still had two churches.) At the time of your correspondent's visit the gate of the enclosure was open, the tape across it severed, but the oppressive and intimidating atmosphere of the village was such that he still feared to enter.

The church building must have been pretty tiny. Not many Baptists in Imber, evidently.

Within the enclosure, though, is perhaps the most poignant thing in Imber. Away from the other graves, and barely visible above the overgrown grass, a tiny marble headstone can still be seen from the outside of the fence. Picked out in simple black lettering on the white marble are the words "IN MEMORY OF THE BAPTIST COMMUNITY OF IMBER". There's no further elaboration, no "political" statement (perhaps for fear that the Army would obliterate it as they did the graffiti on the houses), but it's the closest thing to a memorial for the inhabitants of the stolen village.

Obviously I could have poked the camera through the wire to take the pic, but this way it's ART.

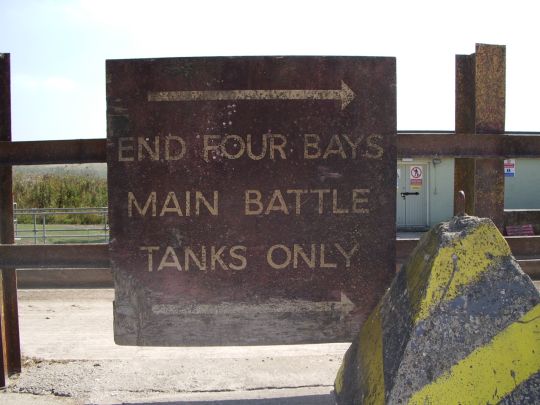

After the Baptist "church", located at the westernmost extreme of Imber, there's little more (that you're allowed) to see. Your reporter returned to his car and - having first been sternly warned by a fat, toothless policeman for exceeding the 15mph speed limit within the village, on the grounds that the cadet soldiers training there that day were "children" - left the modern-day inhabitants to their wargames and drove out onto the plains at the other side. After a couple more miles of tank wrecks and warning signs, you come to the military installation proper (including an excellent tank-washing park), which oddly appeared on the day of your correspondent's visit to be entirely bereft of life.

On no account should smaller tanks be washed in the end four bays.

Somewhere on this western side is also where, years after the evacuation of Imber, the Army actually constructed a second, purpose-built village, in order to provide buildings with cellars which were considered a more accurate recreation of the sort of environment Britain's soldiers would be likely to find themselves attacking in a real war. But unsurprisingly there's no public access to that, and anyway your reporter had seen enough by this point, and utilised the tank-washing park to turn around (resisting the impulse to blast some of the dust off his own car) and head - this time with the stereo off and the 30mph speed limit soberly observed - back to the main road, back into the world on the maps, and on to home.

The long way out.

Below, you'll find some more images of Imber. But WoS recommends that any viewers within a reasonable distance (the drive is about 45 minutes from Bath, and would perhaps take about one-and-a-half hours from the the west edge of London), and with their own transport (it's quite a hike from the nearest train station), take the fleeting opportunity to see this strange, unsettling little corner of Britain for themselves. But you'll have to hurry. The road through the village is open to the public until August 25.

The closest it's currently possible to get to St Giles' Church.

The lengthy notice detailing the laws with regard to Imber.

(Note the harsh £5 penalty for breaking any of them)

A sign AND a barrier? That'll stop those pesky tanks!

If only Saddam had thought to put up some of these.

Probably once a lovely garden.

An extra-tough objective. Use stealth!

At the tank wash, yeah.

Imber's most popular sign.

Tianenmen Square Simulator.

In case you were thinking of digging for buried treasure.

Tank 3 and Tank 4.

Imber skyline.

Safe under the watchful eyes.

|