|

WHY THE

LONG FACE?

The rights and wrongs of Space Giraffe

Making the same two or three

videogames over and over again for 20-odd years can lead developers

in one of two directions. (Actually, three if you count the Metal

Slug option of "make every game exactly the same as the last one".

Or four if you go the Frogger route of simply whoring out your brand

IP to anyone who gives you a cheque. But for the sake of this

particular argument, we'll stick to the main two.) Choose the easier

of the two paths and your games will constantly reach out to an

ever-widening audience, innovating and developing the gameplay while

still remaining accessible to the uninitiated - or even, in an ideal

world, getting MORE accessible and popular with each successive

release.

Indeed, sometimes it's even possible

to make things almost TOO accessible, as in the case of the

Burnout

series. Criterion's high-octane racing line has evolved into

something that's barely recognisable from the debut title (which,

implausible as it might seem to anyone who's played the more recent

versions, was actually about AVOIDING collisions), and

been dumbed down so much along the way that a one-armed gorilla

could clear about 60% of it just by being trained to keep his big

hairy hand gripped around the accelerator trigger.

Not unrelatedly, each new Burnout

sells more than the last. But if you're concerned with things more

important than mere money-grubbing, taking the conceptual high

ground in the name of art is fraught with danger too. In that

scenario, you can all too easily end up with something like the

Street Fighter or Virtua Fighter series, endlessly refined and

tweaked for the benefit of insanely hardcore fans until you get a

game so spectacularly impenetrable to unsuspecting newcomers that

the instructions might as well be written in ancient Phoenician,

full of absurd nonsense about "Z-ism" and reversed air

counter-tackle returning stumble throw blocks, until normal people

run away crying and you're left with an audience of about nine

completely socially-dysfunctional autistic savants in Tokyo.

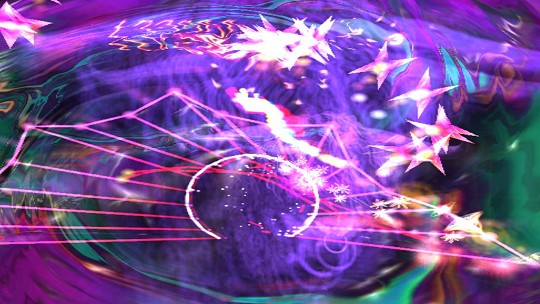

Most of the screenshots which will appear in

this feature are hugely misleading.

Trying to reconcile the conflicting

demands of the iterative sequel, then, is a difficult task, and

nobody embodies the challenges of this very particular situation

better than goat-loving 80s bedroom-coding poster-hippy Jeff Minter. Pretty much

everything the one-man Llamasoft developer has created since 1990

has been a variant of either Defender, Centipede or Tempest, and

it's a gameography which, as alert WoS viewers will already be well

aware, spans the fullest possible spectrum of success and failure. At one end sit stunning triumphs like the magnificent

Tempest 2000 and the superb

independent release

Gridrunner++,

while at the other lurk wretched atrocities like

Defender 2000 and

Tempest 3000.

Even within the confines of a single

design, therefore, we've seen that it's possible for the same person

to get the formula both spectacularly right and hideously wrong. So

when it was announced a year or so ago that Llamasoft was to produce

"Space Giraffe", another new take on Tempest for Xbox Live Arcade,

fans of the super-intense single-screen shooter series tried to calm their

racing heartbeats and held their breath to see which way the space

cookie would crumble. And any minute now, impatient viewers will be

relieved to hear, we're going to get to the end of this

seemingly-unnecessary preamble and find out.

These first two, for example, suggest a

relatively easy-to-discern Tempesty game field.

Right off the bat, though, the game

appears to throw a spaniel into the works by announcing in the very

first line of its play instructions that "Space Giraffe is not

Tempest!", and spends much of manual emphasising the various

differences between the two superficially similar games. There are

in fact just two major fundamental changes to the Tempest gameplay

model, but they're both highly significant. The first one -

directional firing - alters the basic nature of Tempest, by removing

all meaning from the grid lines that separate each level's web into

channels. Once dividing the playfield into discrete segments which

most enemies and all bullets were unable to traverse, the channels

are now mere decoration. Both the player and his enemies can shoot

diagonally across the channels as well as directly down them, and

almost every protagonist can and does move freely across the web.

If Space Giraffe really wanted to set

itself free from the shackles of Tempest comparisons, it would have

done well to dispense with the grid lines, and the only purpose of

leaving them in seems to have been to draw in fans of the existing

titles who might be more wary of a totally unfamiliar design.

However, the other big gameplay change does perform the task which

the graphic design shirks, and turns SG into something with a very

distinct feel of its own by dispensing with the central danger

mechanic of every previous Tempest game.

Since Dave Theurer's original 1980

arcade machine, the biggest threat to the Tempest player has been

enemies who ascend to the outer rim of the web, and by doing so

become practically invulnerable. With no means of shooting to the

side, the player was reduced to last-resort measures like firing his

Superzapper smart bomb or (in the case of T2K), scrambling to

collect the "jump" powerup on each stage and then spending most of

the level pogoing like a punk rock jack-in-the-box to stay away from

rim-riding baddies, missing out on valuable powerups in the process

and turning the game into a bit of a lottery. Tempest 3000's

partially-homing shots were a badly flawed attempt at keeping things

more sensible when enemies reached the upper edge of the grid, but

Space Giraffe finally gets it right.

Static images, however, do a very poor job of

conveying how chaotic the game looks in play.

As you shoot things in Space Giraffe,

you extend your "Power Zone", a brighter area of the web which

extends from the player's edge of the grid down towards the bottom,

and shrinks back towards the player when no enemies are being

destroyed or power-ups collected. As long as the Power Zone is

greater than zero, almost every type of enemy can be rammed (or

"bulled", in the game's idiolect) off the rim. As well as altering

the threat balance, "bulling" also changes the focus of the scoring,

because if you knock a large number of enemies off the edge at once,

you also increase your score multiplier up to a maximum of 9x. Not

only does this revolutionise the basic character of Tempest - now

enemies reaching the rim is a welcome event to be actively sought

and exploited, not a deadly one - but it provides one of the most

rewarding gameplay functions in recent memory.

Bulling off a huge clutch of baddies

in one go, accompanied by the evocative dive-bomber scream of a Star

Wars TIE Fighter and the smashed enemies spinning balletically up

into the air, feels so astonishingly good that you'll deliberately

play yourself into dangerous situations just to get the big narcotic

adrenaline hit again, and that risk-versus-reward mechanic is at the

heart of all of the best arcade games. It's a genius piece of

re-imagining, and practically justifies the absurdly low purchase

price of Space Giraffe by itself.

In isolation, of course, bulling would

make the game incredibly easy. Rebalancing the gameplay after such a

radical modification to its core structure is no simple task, and

it's here that SG first falls down a little, resorting to several rather

cheap methods to counter the player's considerable new-found power.

The most immediately obvious culprits, and the factor which will

probably do the most to scare off new players instantly, are the

graphics.

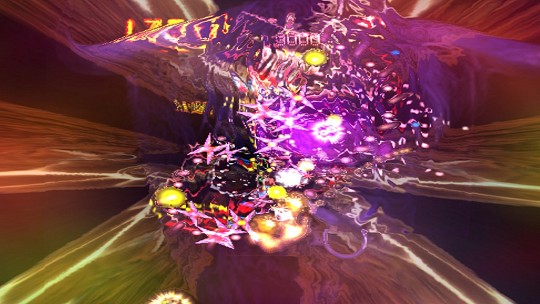

For a very considerable percentage of the time,

you'll be dealing with something more like this.

Graphically, Space Giraffe is frankly

terrifying. On first play, and for a considerable time afterwards,

it seems simply impossible to make any sense out of what's happening

on your screen. The reason for this is that the game is built on the

engine of the 360's built-in music visualiser Neon (also coded by

Minter), and the grid-blasting action is superimposed directly onto

the visualiser in maximum psychedelic tripout mode. It's an absolute

maelstrom of sensory overload which makes even the most extreme

mayhem of Geometry Wars: Retro Evolved look like a faded old

newspaper picture of Pong, and for a great many players the demo

alone will be enough to leave them whimpering in a corner. (In which

case it's probably just as well, as the later stages would be likely

to cause a major psychotic episode.)

The

initial onslaught on the eyeballs is frightening, but after a brief

period of acclimatisation, helped by a non-compulsory but useful

tutorial and some gentle opening levels on which to practice your

new skills, the game starts to make sense. As soon as it does,

however, it whips the rug out from under the player's feet again

with some nasty tricks. The worst of the early ones - in fact,

probably the worst throughout the game - is the appearance of the

Flowers. On first appearance a direct steal from the Spikers in

Tempest, they grow up a single channel towards the player, and can

(usually) be hammered back down with bullets. If left unmolested,

they either explode, sending an indestructible daisy-like head up

the channel, or grow all the way past the outer edge of the web, the

long green stalk presenting an impassable obstacle to the Giraffe's

movement until they either explode, are destroyed with a smart bomb,

or are jumped over using one of the player's single-use jump pods.

While the Flowers are inherently

annoying, that's not the actual problem with them - after all,

enemies are supposed to be annoying, because their entire

purpose is to kill you. The clue is in the word "usually" in the

previous paragraph. The trouble with Flowers is that like real

flowers, they

come in various types, some more dangerous than others. Some are very easy to shoot down to a

manageable size with your bullets, some are much more resistant to

your fire, and some are completely impervious, shrugging off even a

smart-bomb attack without the slightest impediment to their growth

up the web. But unlike real flowers, there are no visual differences between the numerous

varieties to tell you which are the dangerous ones, and having

identical-looking enemies with very significantly different

characteristics is such a glaring piece of empirically terrible

basic game design that it's a complete mystery how it was ever

allowed to get past the playtesters and QA and make

it into the finished product.

An early wave infested with past-the-rim

Flowers.

Aside from the Flowers, the game's

roster of enemies is pretty well-judged, abandoning the

over-complicated excesses of Tempest 3000 for a tighter line-up,

although far too many of them appear with no introduction. There's

no excuse for not including a couple of lines of basic info on each enemy

type in the instructions, leaving the player to either try to work

out some fairly arcane behavioural rules from amid the game's visual

turmoil or hunt around on the internet for an FAQ. Dealing with the

your adversaries is supposed to be the challenge of a videogame, not

working out that (for some unexplained reason) they're invulnerable

to bullets unless they're moving sideways. However, it's still

better to have to figure out a couple of undocumented enemy types

than remember what to do about 17 different ones.

There is one particularly

unwelcome reappearance from the cast of the Nuon game, though, in

the form of the Rotor, a cheap and lazy enemy which spins the web

around and effectively reverses your controls like a bad Amiga

platformer from 1994. In a game where the player's beleaguered

orientation perception already has to contend with webs in spiral

shapes, webs with twisting corkscrew channels and webs where you're

at the bottom end of a conical shape and are effectively playing

"inside-out" - in addition to having to get your head around this

geometry for twice as many elements as before (your directional

firing as well as movement) - also having to suffer an enemy which

effectively makes right left and vice versa several times in a level

is a smug little prank that's barely short of cheating.

The enemies do perhaps also suffer

from looking slightly too similar to each other, all being

constructed from a fairly small set of elements (circles, Xs and

asterisks), but there are surprisingly few instances of mistaking

one for another, partly thanks to the different sounds they make but

mostly due to the way you have to play the game, of which more

later.

Long webs try to tempt you to go bulling

riskily into unseen territory.

Yak-lovers will be pleased to hear

that Space Giraffe's more iniquitous baddies are outnumbered by the

good ones, however. Your reviewer's personal favourites are the

laser platforms which appear somewhere around halfway through the

game's 100 levels, patrolling above the web out of the player's

reach and unleashing deadly beams at regular intervals, signified by

an audible alarm preceding a tremendous deep, fizzing electrical hum

as they fire. (Older viewers will recognise them as descendants of

the laser guns in Gridrunner, an early Minter 8-bit title.) They're

so fearsome it seems odd to call them a "favourite", but there's nothing wrong with

having terrifying villains as long as they're also fair ones, and the clear

aural signals means you'll only ever have yourself to blame for

laser-induced deaths.

Sound cues are one of the areas in

which SG marks a major improvement from T3K, and following them is

an absolutely vital component in learning to play the game - most of

the time, in fact, you'll hear enemies before you see them. (In

general the game is a sonic masterpiece, with superb music in the

vein of the previous Tempests backing up a liberal sprinkling of

well-chosen samples and FX borrowed from the classic Eugene Jarvis

coin-ops of the early 1980s in a mix that's at once cacophonous and

yet never less than clear.)

Pleasingly, the levels themselves are

another area where SG borrows some broken ideas from Tempest 3000

and fixes them, to excellent effect. The simple concept of making

webs be different shapes and/or sizes at either end creates some

incredibly striking and beautiful forms, and having them flex and

move in play works on the 360's smooth high-definition display in a

way that it didn't on the fuzzy, low-framerate screen of the Nuon

game. There are a couple of lowpoints again encoring from T3K, such

as grids which appear to be complete loops but arbitrarily aren't,

but such unfair chicanery is much rarer in Space Giraffe than it was

in its predecessor. (And also doesn't appear until much further into

the game, so most players probably won't ever have to worry about it

anyway.)

This

is the first level in which you have to seriously hone the deadly

art of bullet-juggling.

And that brings us to the elephant in

the zookeeper's lounge where Space Giraffe is concerned, because

pretty much everyone who plays this game is going to have the same

initial reaction - "You can't see what's going on!" And

indeed, you can't. (A disturbingly large amount of the time, it's

pretty hard to even keep track of where your own Giraffe is.) In an attempt at pre-empting

such criticism before the

game was even released, the developer huffily insisted that every

single enemy was visible and audible, and therefore nobody had any

excuse for claiming that they'd been killed by something they

couldn't see. However, there's a big difference between being able

to see every enemy and being able to see all the

enemies. Your reporter has completed almost 80% of the game at the

time of writing this feature, has a moderately respectable highscore

of 126 million (107th out of about 10,000 on the global

leaderboard), and yet could still only claim to have accurately identified the cause of

about one in ten - at the most - of his Giraffe's deaths. The idea that every single

danger can be seen and identified before it kills you is technically

true, but highly disingenuous.

Collective action is your adversaries' secret. Whether enemies are

discernible in isolation or not, the game is so overwhelming that it

just isn't humanly possibly to consciously observe or track all of

them. Most of the time you'll be focused on one small part of a

grid, trying to stay alive, fend off bullets or build up your Power

Zone in readiness for a bit of bulling, and suddenly looking over at

the other side of the web to see a Flower landing or spot a Boffin

starting to fire diagonally would simply get you obliterated in a

fraction of a second.

Key to your survival, then, is

observing things unconsciously. Tempest players often speak

of it being a "zone" game, one where you have to feel danger

rather than see it, or more picturesquely of "using the Force", but

what you actually have to employ in situations like those presented

in SG is a mixture of subconscious reasoning and peripheral

perception.

Even though you don't have time to

process the game's avalanche of visual and aural information,

it's still there in your brain - you simply have to trust your brain

to accept it and act on it without verifying it with your conscious

mind first. If you're travelling to the left, firing behind you as

you go, and you hear the distinctive sound of your bullets hitting a

flower, then if you're heading back to the right a couple of seconds

later, your brain knows that there's a flower there somewhere,

and you'll have an instinct to be cautious even if you can't

actually see any peril through the pyrotechnics. As long as you

don't try to overrule that instinct with your conscious mind, you're in

"the zone" and you'll stop short of the danger.

Level 64 (which this is) can only be

played in "the zone".

Regular viewers of WoS might be mildly

surprised to hear this reviewer defending a game in which 90% of

deaths are of unknown origin, but the fact is that Tempest and

similar games have always been about that kind of gameplay - even if

you don't know exactly what killed you, you know why

you got killed. And it's interesting to note that despite the

substantial alterations to the central ruleset and the protestations

of the developer, the longer you play Space Giraffe the more like

Tempest it gets. By the time you're in the later levels, you're far

too busy trying to stay alive in the spinning, pulsing, distorted,

kaleidoscopic webs to be worrying about cultivating bulling

opportunities to boost your multiplier, and the game reverts to a

frantic blast-them-before-they-blast-you contest more akin to its

ancestors.

Tallying a good score, then, becomes

about maximising your harvest in earlier stages, using the inventive

save system. As long as you finish a level with at least three

lives, you can "save" your score, which becomes the starting bonus

if you subsequently start a new game by clearing the next level. (It

makes sense in practice, honest.) At any time, you can go back and

try to improve your score on any level, and if it's better than the

saved one it becomes the new start bonus for the next stage. As

insignificant as this sounds, it's actually one of the most

intriguing design features of Space Giraffe, and one which provides

the game with considerably more depth for the less-skilled player

than it at first appears to have.

Real hardcore players are catered for,

appropriately enough, by the "Hardcore" leaderboard, which only

records scores from games starting all the way back at the first

level. (And they can also unlock an even harder "Super Ox" mode

too.) Gamers of more moderate ability can still garner an

impressive-looking score for the "Overall" rankings by repeating

levels over and over until they've racked up as many points as

possible, then using them as starting points to do the same on the

next level until they've maxed their way more meekly to the end. And

the klutzish can still get value for their money and a sense

of achievement by simply bludgeoning their way through the levels

one at a time, by judgement or luck, until they've beaten all 100.

If you beat a level with fewer than three lives remaining you'll be

starting from 0 points each time even when you're continuing from

Level 99, so your score will be pitiful but you'll still feel like

you've bravely overcome a tough challenge, and you will have.

Rainbow Ripple would be a great flavour

of ice cream.

Unquestionably, despite the above this

isn't a game for everyone. Space Giraffe is so unlike almost

everything else currently in existence that it will unfeelingly

steamroller the average teenage Xbox owner from Bumhole, Idaho in

four

minutes flat. But the developers deserve a lot of kudos for offering

a multiplicity of approaches to the game which ensure that anyone

who plucks up the nerve to tackle what at first seems horrifying and

impossible will get something out of it. It's a shame that that

consideration didn't extend as far as a Beginner mode where the most

extreme graphical excesses were turned off, so that players could

get a feel for the actual game mechanics before taking on the full

experience, but that's probably the price you have to pay in 2007

for a game that's basically one person's sole and heartfelt artistic vision,

untainted by the malign influence of focus groups and marketing clowns.

Final among the

game's praiseworthy features are the Achievements. In too many Live

Arcade games these are handed out so casually that you won't even be

aware of earning them, but SG makes you work for every point with a

varied and testing collection of challenges which add even more to

the breadth of ways you have to play the game. For example, one

Achievement requires you to beat 16 levels in a row without losing a

single life (actually monstrously difficult), while others ask you

to keep a single Flower alive throughout a level, or boost your

multiplier to 9x in a single bull run. Almost all of the

Achievements require very different approaches and styles of play,

and whether you want to play

Space Giraffe for five minutes or five hours, there's a mode in

there somewhere for you.

We haven't even touched on the blizzard

of jokes and cross-cultural meta-references.

At the end of the day, the truth is

that SG is an unmissable experience for anyone with a 360. The price

is so ridiculously tiny (£3.40 in UK money, falling to as little as

about £2.60 if you take advantage of current exchange rates and buy

your MS Points from the US via eBay) that even if you only use it to

freak out people who come to your house or make your drunk friends

throw up after the pub, you'll get your money's worth. But that's

damning it with faint praise. If you're prepared to open your mind

and learn a new way of playing, this is simply a brilliant game in

its own right regardless of the price. It's easy to hate it on

sight, and it's easy to give up after an hour. And if you're

unfortunate enough to have encountered them, it's easy to be put off

by the people who made it. But the game itself doesn't deserve that

fate.

Xbox Live Arcade has been a revelation

for fans of (what's rather short-sightedly and inaccurately called)

old-school gaming. As well as a lot of retro shovelware, it's hosted

some fantastic brand-new games in styles that wouldn't have been

economically viable any other way. Space Giraffe belongs right up at

the top of that list alongside Jetpac Refuelled and Geometry Wars:

Retro Evolved, but in fact it even transcends that. Despite a few

irritating, thoughtless and needless flaws, this is one of

the best games released this year at any price, and for the sake of

all of us, you owe it a chance.

|