|

"I JUST WORK HERE"

One night with Elvis.

I wouldn't, in the

normal scheme of things, describe myself as an Elvis Presley fan.

After a brief dalliance with glam rock (in the shape of The Sweet)

in the early 70s, it was punk that really awakened my interest in

music, and Elvis died just as punk broke, so he never meant anything

to me while he was alive. And when you look back at his career from

the perspective of the present day, the good bits make up a tiny

proportion of the 20 years it lasted. For 95% of that time, Elvis

was a puppet in the hands of his manager Col. Tom Parker, who

squandered what it turns out was probably the greatest natural

rock'n'roll talent of all time making cheesy movies and then

becoming a tragic cabaret act - doped to the eyeballs, dressed like

a Christmas-tree fairy and searching in desperate bewilderment for a

faintly-remembered spark of burning soul from a distant past, whose

occasional brief flickers through the Vegas sludge only served to

illustrate the tragedy all the more painfully.

So if Elvis was

crap nearly all the time, how do we know he was probably the

greatest natural rock'n'roll talent of all time? Because, chiefly,

of Elvis - One Night With You.

Sorry, ladies - he's dead.

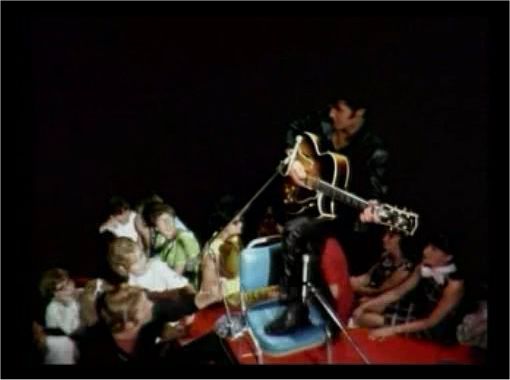

The 1968 Comeback

Special is generally held up as the definitive example of Good

Elvis. A made-for-TV extravaganza (which wasn't actually called the

"Comeback Special"), it briefly resurrected Presley's career after a

load of terrible hack movies had sent his rock'n'roll reputation

plunging almost out of reach into the dumper. The Special showcased

many elements of the 1968 Elvis - there were big glitzy dance

numbers, white-suited gospel sections and all sorts, but the heart of it is a

handful of breathtaking "unplugged" performances by Elvis and some

of his band, seated on stacking chairs on a tiny stage like a boxing

ring in the middle of a small audience.

This performance,

removed from the rest of the Comeback Special (in which only a small

fraction of it was included) and depicted many years later in a separate US TV

show and subsequent video release in its unedited

entirety, is what makes up

Elvis - One Night With You. It's probably the greatest piece of

unadulterated, pure rock'n'roll ever committed to film. Join your

reporter now on a guided tour.

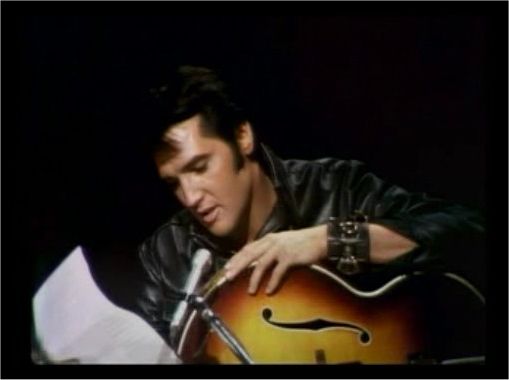

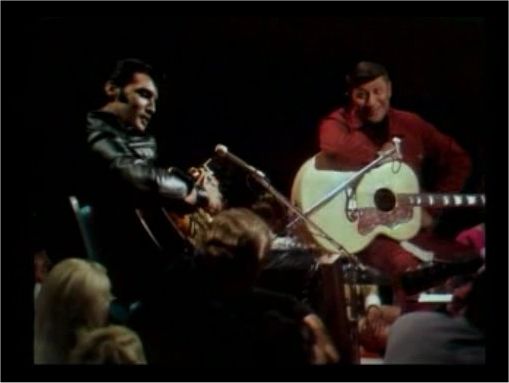

Rock'n'roll Babylon.

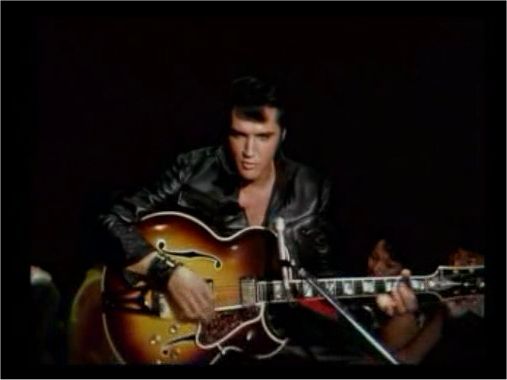

Elvis, in a tight

black leather suit, holds court with four old session guys in red

garage-mechanic-style overalls. Two of them (and Elvis) have

guitars, one plays bongos, and the last (Elvis' long-serving drummer

DJ Fontana) plays drums on a guitar case resting on a small table

between the players, as if they were all just rehearsing in a small

living-room. (Next to Elvis is his veteran guitar player Scotty

Moore, and the other two musicians are Elvis' long-time friends

Charlie Hodge and Alan Fortas, but this reporter is sadly unable to

relate to minor-detail-loving viewers which one's the guitarist and

which is on the bongos.)

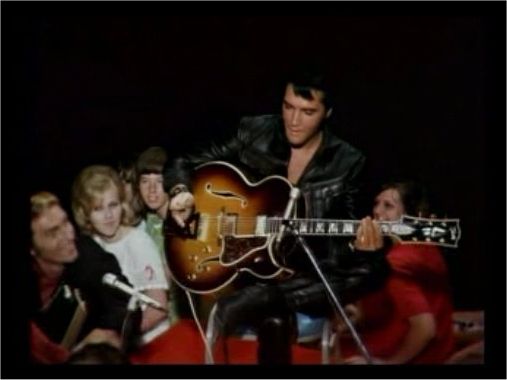

A younger man,

never introduced and not dressed like the others, kneels on the

steps at the edge of the stage and bangs a tambourine in time with

the drums. (It's never made clear if he's part of the band, the

studio floor manager, an audience member, the pizza delivery guy or

what.) Add a few textbook clean-cut young adults (this isn't a teeny

screamer audience, as the Comeback Special was aimed at restoring a

certain amount of grown-up artistic gravitas to Elvis' image) and

the picture is complete (alternatively, you could just look at the

pictures). Which leaves us only the performance to talk about.

The blond man at bottom left is Mysterious

Tambourine Guy.

(Later immortalised by the Byrds in "Hey, Mysterious Tambourine

Guy".)

From the opening

seconds, One Night With You is a thing of beauty. Even a cheesy,

bizarrely-punctuated voiceover intro only seems to add to the

atmosphere, and from the minute Elvis and the band arrive onstage

everyone seems relaxed and happy. There's a couple of minutes of

warm, chatty intro and banter, then without any ceremony the band

kicks into "That's Alright Mama", an old blues standard that's

rendered with an easy playful charm that doesn't quite conceal the

raw fire in its heart. Then it's straight into "Heartbreak Hotel",

Elvis occasionally getting up off his chair to knowingly-obliging

squeals from the audience or pretending to forget the words, and

everyone's having a great time already.

The smoky

crooner-ballad "Love Me" is next up, showing off Elvis' rich,

reverberating baritone to great effect, but the casual, gently-paced

start to the show's about to come to an end. At the end of the short

song, Elvis swaps his acoustic guitar for Scotty Moore's beautiful

big sunburst Gretsch electric, and the heat's turned up a little

with the feral stomp of "Baby, What Do You Want Me To Do?".

The Elv reading theatrically from the "script".

But it's a tease -

after it's finished, Elvis picks up his set instructions and embarks

on a pisstake of them, then starts on a curiously serious and

seemingly improvised monologue about the state of music,

("Everything's improved") how he enjoys the new groups like

"The Beatles, The Beards, and the... whoever" but how

rock'n'roll is basically just a derivative of gospel and

rhythm'n'blues, and how... the audience is gazing in rapt attention,

hanging on every word and waiting for the point, but then just as

it's getting interesting he slyly gives up on the ramble, links

slickly into "Blue Suede Shoes" with a little in-joke that

the band get before everyone else and we're off again.

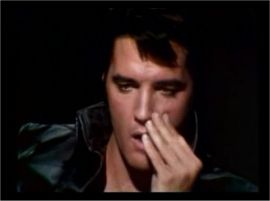

It's after "Blue

Suede Shoes" that the show really catches light. Jamming

inexplicably back into "Baby, What Do You Want Me To Do?", Elvis

breaks the song off after the first chorus, complaining that

"There's something wrong with my lip". This is the excuse for an

anecdote about the infamous restrictions imposed on his early TV

performances, and the first of several oblique and not-so-oblique

references to the unwanted demands made by Col. Parker on Elvis'

career direction (especially the terrible films). This is candid

stuff, and the first sign that this is the real Elvis we're

watching, relaxed and intimate among friends and doing the only

thing he really wants to do - play simple old rhythm'n'blues rock'n'roll, for himself and for

his fans, and with his best and trusted buddies beside him.

"I got news for you, baby", reveals Elvis. "I

did 29 pictures like that."

At this point, that

rock'n'roll takes the form of the ferocious, lustful "Lawdy Miss

Clawdy", another blues standard in much the same vein as the earlier

songs (in fact, the tune is all but indistinguishable from "Baby,

What Do You Want Me To Do?"), and for the first time Elvis really

lets his voice go, as if released and empowered by speaking a

long-bottled-up truth.

It's followed by

the jauntier, poppy "When My Blue Moon Turns To Gold Again", but

just 45 seconds in, Elvis realises he's supposed to be doing a

different song and cuts it short to go straight into "Blue

Christmas". It's a charged rendition, Elvis suddenly short on the

big smiles that have punctuated the performance so far and staring

at the floor for most of the song, as if realising that the earlier

display of dissent might not have been such a smart move.

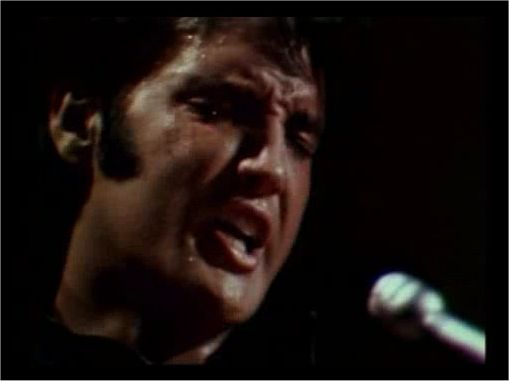

This (whether real

or merely invented by the over-imaginative viewer) internal

conflict, though, finds stunning voice in the next song. Suddenly

reinvigorated, Elvis delivers an incendiary, primal version of the

powerful torch-blues of "Trying To Get To You" that marks the start

of the show's most spine-tingling section. He gives the song

everything, provoking spontaneous applause from the audience in the

middle as he howls the song's yearning lyrics like they're the most

important words anyone's ever had to convey. The song seems to have

a physical hold on Elvis, pulling at his arms and forcing him up out

of his chair on several occasions, hips swinging in spite of the

lack of a guitar strap making it impossible to stand up properly. As

it comes towards its end, he urgently growls "One more time, one

more time, one more time" and the band obligingly and seamlessly

carry on for an extra chorus.

Trying to get to us, and succeeding.

As he turns the

intensity up another notch and shakes his guitar like a fist, it's

easy to imagine that the song's lyrics are now about Elvis' own

life, his much-frustrated and delayed journey to be right here,

right now, just singing his rock'n'roll songs to us - "There was

nothing that could hold me! / Or could keep me away from you!" -

and free for a single blissful moment from the grisly circus run by

the overbearing Parker. Unable to keep the song going any longer,

Elvis plunges without pausing into the next number, the slower but

equally taut "One Night With You" that gives the show its title.

He's still in the music's grip, grimacing and twitching and shaking and jerking

out of the chair like a rag doll every time the song peaks in the

choruses between the ballady verses, and extending it with more and

more choruses as if he never wants this perfect moment to end.

There's an

incredible bit near the song's usual finish, when an audience member

knocks out the lead of Elvis' electric guitar, and the song stops

dead. With the minimum of fuss, Elvis plugs back in, and with a

quick "What I was gonna say was - " dives straight back in

and picks up exactly where he left off without losing a single iota

of the song's built-up power or fearsome drive, and then seizes the

excuse - "Gotta do it again now, I'm sorry" - to get in yet

another refrain of practically the whole song, building to an

electrifying climax where it looks like the whole band are going to

get up and rock the place right to the ground, only for Elvis'

missing strap to bring him back down to Earth and the rest of the

band with him.

Scotty Moore shares a joke about bad wigs.

But they're set free

now, undaunted by such trivialities and doing whatever the hell they

please, so Elvis leads the band straight into "Baby, What Do You

Want Me To Do?" for a we-don't-give-a-fuck third time

(maybe playing this particular tune three times in the show is a

coded or spontaneous message of exasperation aimed at Col. Tom

Parker and the other malign influences in Elvis' life, but probably

more likely they just love the song) and they tear the place up,

stamping the floor like bulls and yelping and growling their way

through the song like nothing else in the world will ever matter. It

goes on and on, longer than the two

previous renditions put together, until it seems to put everyone,

band and crowd alike, into some sort of a hypnotic trance.

An instrumental

break at the end of the song seems to stop time, everyone just lost

in the primitive repetitive single beat of the music and locked into

an endless groove, until finally someone remembers to do the last

chorus and bring the thing to an exhausted, sweating halt, Elvis and

the other guitarist sharing a knowing look as they croon the last

lines softly across the stage at each other, because they've

realised that nobody's ever been this good before and nobody will ever be

this good again - they own the soul of rock'n'roll forever.

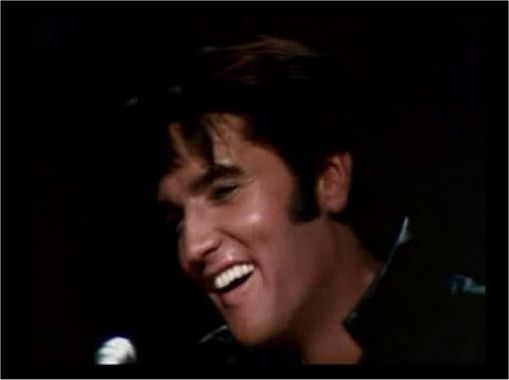

Happy Elvis.

The show proper is

effectively over at this point, and as everyone gets

their breath back after the thrilling scenes they've been witnessing, Elvis is momentarily lost for words, stammering

"Uh... uh... what? Help" in the quiet moments after

"Baby What Do You Want Me To Do?" has finally come to an end

for the last time. As if belatedly remembering where

he is, he gathers his thoughts and tells the audience that there's

only one more song to come, as "There's another audience waiting

to come in" (the other audience being presumably for the

recording of one of the other, stagier sections of the Special).

As a loud groan

goes up from the disappointed crowd he makes his

excuses in a jokey comment, but one that's also loaded with meaning

and sadness

reflecting how rarely the world's biggest star actually gets to do

what he really wants to do - "Man, I just work here!" - and the band get ready

for the last number. Elvis decides he's going to put a strap

on his guitar and stand up, but it transpires that there's no strap

to be found. A hurried discussion follows, and one of the guys

suggests Elvis could rest his foot on the chair and balance the

guitar on his knee and still be able to put out some hot

pelvis-thrusting action.

The other guitarist

puts down his instrument and hastily enters service as a mic stand,

holding up Elvis' microphone (set for a sit-down performance) at

stand-up singing height and there's a second, apparently

spontaneous, rendition of "One Night With You" that starts off as a

joke with improvised lyrics about the missing strap but turns into a

stirring, hip-swinging farewell, with beaming grins on everyone's

faces as they show the world how it should be done, just one last time.

"I wish I'd brought a smaller guitar."

Annoyingly, though, it's not actually the last song of the show -

there's a pre-arranged, pre-recorded version of the slushy ballad

"Memories" for Elvis to croon along with, bizarrely out-of-place

among the raw blues classics heard up to now and lending the show a

weird, unsatisfying endpiece as the music barges in long before the

applause for "One Night With You" has faded away and the band are

hustled off into the shadows without a goodbye, evidently having had

so much fun jamming with the boss like in the old days that the

show's running time is now under severe pressure. It seems like a

metaphor for Elvis' entire life. "Memories" ends

abruptly and the credits - complete with Elvis' name misspelt -

roll.

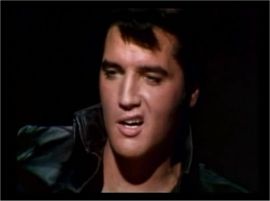

Elvis - One Night

With You is a fantastic rock'n'roll performance in its own right,

but it's everything else it stands for and carries with it that

makes it one of the great cultural documents of the television age.

It's perhaps the only recorded instance on film of Elvis doing the

thing he was born to do, freed from the crushing weight of

contractual obligations with which Col. Tom Parker almost destroyed

him. It's a record of someone lost in sheer joy, doing what he loves

most surrounded by people he loves; totally relaxed yet at the same

time radiating raw sexual tension like an exploding star radiates

raw fire and light. And it's pretty debateable whether any human has

ever looked as good as Elvis does in this show.

Do my hips look big in this?

And yet there's

more. This isn't some invincible god putting on a performance, this

is someone unselfconsciously sharing their true personality, which

just happens to be as magnetically watchable as a fireworks display

at the end of the world. There are glimpses of vulnerability, candid

nods at the darkness that this night is a release from, an

acknowledgement of a man's lack of control of his own life, all the

wasted years when Elvis could have just been doing this instead of

throwing his incredible talent away on making cheap bucks for evil

manipulators. It's a microcosm of the story of every artist ever

chewed up and screwed up by the music industry, a parable of the dangers of letting

parasites, middlemen and beancounters hold sway over the creative

and the gifted. (That the warning still hasn't been heeded nearly 40

years later only adds extra poignancy to the story.)

But you don't have

to be looking for cultural or socio-political significance to be

thrilled like a kid at Christmas by One Night With You. The first

time this viewer saw it, he had to watch it through the gaps in his

fingers, because the sheer overwhelming natural power of it was like

looking at the sun during an eclipse - trying to take the whole

thing in at once would just have overloaded and burned out the

senses. If you've seen it and disagree, get them to dig a hole for

you now, because there's nothing left for you to see in this world

that'll touch your cold, dead heart. (You don't need to like Elvis

or the songs to see the beauty in this film.) And if you haven't, you need

to.

The VHS release of

One Night With You has been out of print in the UK for years, and

it's never come out on DVD here, but - well, World Of Stuart is sure

it doesn't have to tell you where to

look for things like

this that nobody will sell you honestly. And with the man dead for

nearly 30 years, the parasites who killed the golden goose in the

first place have made enough money from his living body and his

corpse already. Elvis - in this performance especially - belongs to

the world now. The world should take care not to lose him again.

Is everybody happy? For now, yeah.

|